Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the skull in a toddler

Clinical History

A 3-year-old female patient was referred to the department of radiology complaining of a painful cranial swelling on the right side. The swelling was first noticed following a fall on the head 1 month ago and did not regress over time. No neurological or other systemic symptoms were noted.

Imaging Findings

Computer tomography (CT) showed multifocal osteolytic lesions scattered throughout the skull with non-sclerotic borders and asymmetrical involvement of the inner- and outer table (bevelled edges) (Figure 1). A hypodense subgaleal soft tissue swelling is noted at one of the larger lesions.

Ultrasound (US) revealed multiple defects at the calvaria with intralesional solid soft tissue lesions of heterogeneous echogenicity. Color doppler showed subtle intralesional flow (Figure 2).

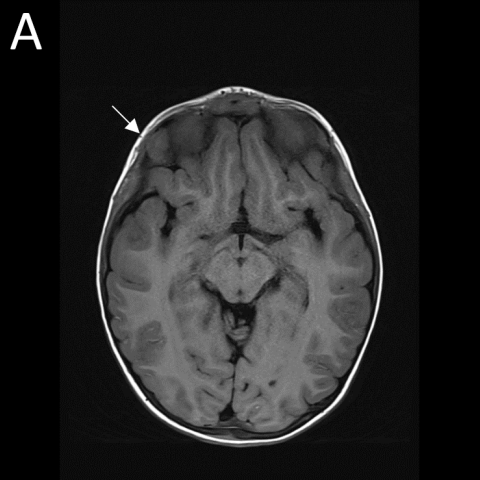

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed multiple calvarial lesions, all iso-intense to adjacent brain tissue on T1-weighted images (WI). One of the larger lesions was located peri-orbitally, and slight proptosis was noted. On T2-WI, the lesions were heterogeneously hyperintense, and after administration of gadolinium contrast, there was vivid heterogeneous enhancement. A subtle dural tail was seen adjacent to some lesions. Limited diffusion restriction was noted (Figure 3). In addition, there were multiple lytic lesions at the skull base.

Discussion

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disorder, more common in children, characterized by idiopathic clonal proliferation of histiocytes, also called Langerhans cells, a type of immunological cell [1].

Proliferation can occur in various organ systems such as skin, lungs, central nervous system, liver, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. Depending on whether one or more systems are affected with single or multiple foci, we refer to single- or multisystem and uni- and multifocal involvement. Skeleton involvement is frequent and can involve either single or multiple bones with preferred locations in the pelvis, long bones, spine and skull. A solitary skull lesion in children is the most common presentation of LCH [2].

Clinical findings depend on the lesion’s extension and location of the disease. Skull LCH usually manifests as a painful swelling at the scalp [3].

When dealing with a lump at the scalp, ultrasound (US) is usually the initial examination in children in order to avoid radiation exposure. Although the diagnosis may be suspected on ultrasound by demonstrating a skull defect with adjacent soft tissue swelling, final diagnosis is rarely done on US alone.

The typical radiographic appearance of cranial involvement are ‘punched out’ osteolytic lesions without sclerotic rim nor periosteal reaction in the initial phase. Due to uneven destruction of the inner and outer cortical table, a double contour or a ‘hole in a hole’ can be seen corresponding to ‘bevelled edges’ on CT [4]. The lesions do not cross the sutures and sometimes intralesional ‘button’ sequesters are seen.

MRI is the modality of choice for the assessment of central nervous system (CNS) extension. Lesions are typically isointense to brain tissue on T1-WI, heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-WI and diffusion restriction is often noted. Enhancement is variable and sometimes enhancement of adjacent dura will be seen [4]. The final diagnosis is made by histological examination after biopsy [3].

In multifocal cranial LCH, systemic treatment is initiated if more than 2 lesions are present, lesion diameter exceeds 5 cm, or CNS risk bones are affected. CNS risk bones, like orbita or mastoid, indicate increased risk of developing diabetes insipidus or neurodegenerative CNS LCH, referring to CNS affection and development of symptoms such as dysarthria, ataxia and behavioural changes [5]. Prognosis of LCH depends on the extension of the disease, with a very good prognosis in focal disease and a mortality exceeding 50% in multisystemic dissemination under the age of 2 [6].

Written informed patient consent for publication has been obtained.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Multifocal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

CT of the skull with 3D reformat

Lesion ultrasound

MRI of the brain

Medical Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

Cranial CT in this pediatric patient shows a localized “punched-out” lytic lesion in the right cranial bone, with irregular or “beveled” edges and no obvious sclerosis or periosteal reaction around it. The three-dimensional reconstruction reveals uneven destruction of the outer and inner tables, forming a localized hole-like defect. Ultrasound examination indicates that the scalp mass corresponds to the area of bony destruction, along with increased blood flow signals. On MRI, T1-weighted images show a lesion signal that is close to or slightly lower than that of the brain parenchyma, and on T2-weighted images, it appears hyperintense with mild to moderate heterogeneous enhancement. Adjacent dura mater also demonstrates enhancement. No evidence of lesion breakthrough into the intracranial parenchyma or invasion of brain tissue is observed.

II. Potential Diagnoses

-

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH):

A typical singular cranial lytic lesion. The patient’s age and clinical signs (scalp mass, tenderness, but no neurological symptoms) are consistent with LCH. It often presents with a “punched-out” lytic lesion, which is the primary consideration in this case.

-

Infectious or inflammatory bone disease (e.g., osteomyelitis, localized abscess):

Although these can also show lytic changes and local swelling, they are usually accompanied by fever, redness, or abnormal blood tests. Imaging often shows periosteal reactions or significant soft tissue inflammatory changes, which are not consistent with this case.

-

Benign bone tumors or tumor-like lesions (e.g., bone cysts):

Some may show lytic changes but lack the obvious “punched-out” and irregular destruction of both the inner and outer tables, and scalp masses are less common. This possibility is relatively lower.

-

Metastatic lesions:

Skull metastases in a 3-year-old are rare. Clinical history of malignancy, comprehensive systemic examination, and other evidence would be needed to confirm or rule this out.

III. Final Diagnosis

Combining the patient’s age, clinical presentation, and the characteristic “punched-out” cranial lytic lesion, pathological biopsy confirms or highly suggests Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH). If further confirmation is needed, histological and immunohistochemical tests (CD1a, S100 positivity) can be performed.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Treatment Strategy:

- For solitary skull lesions of LCH in a relatively stable condition, local curettage or simple follow-up observation may be considered.

- If the lesion shows progressive growth or appears as multiple lesions, local surgical management (curettage, bone grafting) plus systemic therapy (e.g., corticosteroids or chemotherapy) should be considered.

- Regular follow-up includes repeat imaging and clinical evaluations, especially to monitor for involvement of other systems (skin, lymph nodes, central nervous system, etc.).

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP principle example):

- Frequency (F): 2–3 times per week initially, gradually increasing to 3–4 times per week based on recovery.

- Intensity (I): Begin with low to moderate intensity (e.g., light walking, gentle indoor activities), avoiding any vigorous activities that may risk head trauma.

- Time (T): Start with 10–15 minutes, gradually extending to 20–30 minutes. Ensure the child does not experience excessive fatigue or pain during activity.

- Type (T): Choose gentle, playful exercises, parent-child interactive gymnastics, or short-distance walks to connect with nature safely.

- Progression (P): As the condition stabilizes and tolerance improves, consider introducing simple balance training and flexibility exercises under the guidance of specialists.

- Volume (V): The total volume depends on the child’s daily activity tolerance. Monitor temperature, heart rate, and other parameters; discontinue if any significant discomfort occurs.

Throughout this process, special attention should be paid to the fact that the child’s skeleton is still developing; high-impact or collision sports must be avoided. If increased pain, recurrent local swelling, or systemic symptoms (e.g., fever, fatigue) appear during recovery, immediate medical consultation is advised.

Disclaimer

This report provides a reference analysis and cannot replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. The specific diagnosis and treatment plan should be determined based on further pathological examinations, laboratory results, and specialist opinions.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Multifocal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis