An 80-year-old woman was referred to our institution due to worsening of long-standing pain and limited motion of the left shoulder. She reported a history of a fall on that shoulder six weeks earlier. The laboratory studies were unremarkable.

An 80-year old woman was referred due to worsening of long-standing pain and limited motion of the left shoulder. She reported a history of a fall on that shoulder six weeks earlier. The laboratory studies were unremarkable.

Radiographs of the left shoulder revealed bony erosion with complete destruction of the humeral head, joint space narrowing, and a large soft tissue swelling with extensive amorphous calcifications (Figure 1).

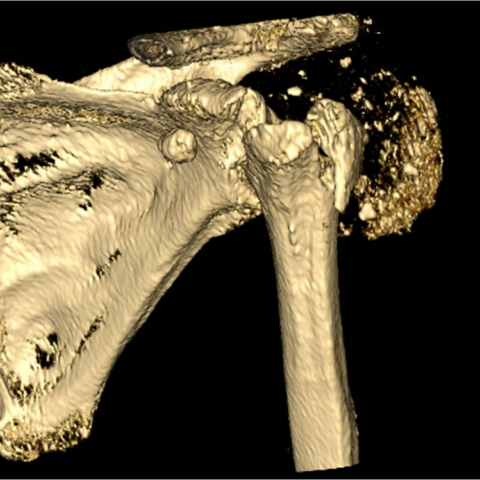

Computer tomography (CT) of the left shoulder was performed to assess the extent of bony destruction which was proven to also involve the left glenoid cavity, acromion, and coracoid process (Figure 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination was limited due to patient movement. Proton density (PD) transverse and T2 fat-suppressed paracoronal images where acquired. MRI confirmed the radiographic findings and better demonstrated the massive tear with retraction of the rotator cuff (Figure 3).

Bacterial culture of the joint fluid was negative.

Due to the extensive bony destruction no surgical treatment was undertaken.

Subsequently the patient developed similar complaints on the right knee without history of trauma. The right knee radiographs demonstrated extensive bony destruction of all joint components with similar semiology to that depicted in the shoulder radiographs (Figure 4).

Milwaukee shoulder syndrome (MSS) is an uncommon and enigmatic entity. It is characterized by rapid and severe joint destruction, which associates rotator cuff tear and atrophic osteoarthritis, and bears resemblances to neuropathic and neuropathic-like arthropathies. MSS has been called rapidly progressive osteoarthritis, apatite associated destructive arthritis, cuff-tear arthropathy, rapid destructive arthritis, idiopathic chondrolysis, and senile hemorrhagic shoulder syndrome. This diversity of nomenclature to address the same disease relates to the controversy surrounding its pathogenesis which still remains unclear. The role of hydroxyapatite crystals on MSS has motivated much controversy, most likely being a marker of osteolysis or a secondary event rather than a primary cause.

MSS preferentially affects female, elderly, and osteopenic patients. Although the shoulder involvement predominates, the knees and the hips are also frequently affected. Bilateralism is observed in the majority of cases. The knees and the shoulders are implicated together in 50% of cases. Other sites as elbows, ankles, wrists, and intertarsal joints are seldom affected.

Most patients complain of pain, joint swelling, and movement restriction that can date from several months to years. In 25% of cases, MSS is preceded by overuse or trauma, including recurrent subluxation, a fall, or a motor vehicle accident.

There is striking structural joint damage associated with rotator cuff tears and severe instability. Joint effusion is often voluminous, blood-stained (80%), and contains hydroxyapatite and less commonly pyrophosphate crystals.

The best documented and mainstay technique for the diagnosis of MSS is plain film. Early radiographic changes consist of a high-riding humeral head due to rotator cuff tear, with mild subchondral bone sclerosis, and narrowing of the glenohumeral joint space, with little or no osteophytosis. These changes may stabilise or show minimal cartilage erosions for several years, followed by sudden and dramatic deterioration. The bones on both sides of the joint are severely damaged, with extension into the undersurface of the acromion, the coracoid process, and the distal clavicle. Pseudoarthrosis between the humeral head, coracoid, and acromion is common.

Although ultrasound can demonstrate the rotator cuff tear and marked joint distension with fluid and echogenic debris reflecting synovial proliferation, blood clots, calcified deposits, and osteolysis, it cannot accurately differentiate MSS from the more common rotator cuff disease related to osteoarthritis.

MRI can have a complementary role in this behalf, more objectively and extensively demonstrating the soft-tissue associated changes. It should be noted that it requires correlative analysis with the radiographic studies, to avoid misleading diagnosis due to the extensive soft tissue changes. CT can be helpful in detailing the bony destruction and pre-operative planning.

Therapy can include analgesia and repeated arthrocentesis followed by intra-articular steroid administration. In the advanced disease, shoulder arthroplasty may be considered.

The case presented perfectly exemplifies the MSSs’ characteristic epidemiology, clinical setting, location, evolution, as well as the distinctive combination of destructive and atrophic joint changes observed by imaging. Indeed, the diagnosis of this uncommon and fascinating destructive arthropathy benefits greatly of the integrated analysis of all these distinctive data.

Milwaukee shoulder syndrome

Based on the provided X-ray, CT, and MRI images of the left shoulder joint, the following key features are observed:

1. Significant destructive changes on the articular surface of the shoulder joint, upward migration of the humeral head, markedly narrowed joint space, and focal areas of notable bone destruction and resorption.

2. Varying degrees of bony erosion observed under the acromion, coracoid process, and the distal end of the clavicle, forming pseudo-joint-like changes.

3. Increased fluid signal or effusion in the joint capsule region, with MRI showing internal heterogeneous signals (possibly bloody exudate or calcific deposits).

4. Some images reveal tears or defects of the supraspinatus tendon and other rotator cuff tendons, indicating damage to the rotator cuff functional structures.

5. Similar degenerative changes and joint space narrowing are noted on knee imaging, suggesting possible multi-joint involvement.

6. Laboratory tests show no significant abnormalities, essentially ruling out acute infection or obvious systemic inflammation.

Taking into account the medical history (long-term shoulder pain, recent history of trauma), age, and imaging characteristics, possible diagnoses or differential diagnoses include:

1. Milwaukee Shoulder Syndrome (MSS): Typically seen in older adults with relatively osteoporotic bone structure, often presenting as rapid shoulder joint destruction, rotator cuff tears, and minimal or no osteophyte formation, accompanied by bloody joint effusion and hydroxyapatite crystal deposition.

2. Degenerative arthritis secondary to rotator cuff tear: Common among the elderly, but imaging usually indicates a more gradual degenerative process. The extent of joint destruction is generally less rapid and extensive compared to MSS.

3. Neuropathic arthropathy (Charcot joint): Common in conditions involving sensory deficits (e.g., diabetes mellitus, spinal cord injury), leading to ongoing joint damage and destruction. However, there is no clear evidence of neuropathic pathology in this case.

4. Other crystal-induced arthritides (e.g., gout or pseudogout): If the joint fluid only contains uric acid or calcium pyrophosphate crystals, these might be considered. However, the clinical presentation does not fully match these conditions.

Given that the patient is an elderly female with chronic shoulder pain and functional impairment, recent trauma exacerbating symptoms, and imaging findings consistent with a rotator cuff tear, extensive bone destruction, and hemorrhagic joint effusion, the most likely diagnosis is Milwaukee Shoulder Syndrome (MSS). This syndrome is relatively common in older women and is typically associated with hydroxyapatite crystal deposition and degenerative rotator cuff tears, with clinical and imaging findings that closely match this case.

1. Conservative Treatment

- Pain Management: Oral or topical pain medications (e.g., NSAIDs) can be used to relieve pain. Short-term oral administration or intra-articular injection of corticosteroids may be considered if needed.

- Joint Aspiration and Lavage: Aspiration of the bloody effusion may be performed repeatedly if necessary, followed by corticosteroid injection to reduce inflammatory reactions.

- Protection of Joint Activity: Avoid excess load and repeated impact to help prevent further soft tissue and bony damage.

2. Surgical Intervention

- In cases of severe late-stage destruction, shoulder arthroplasty (anatomic or reverse shoulder replacement) may be considered. The decision for surgery should be based on overall evaluation of pain severity, degree of functional impairment, and the patient's general condition.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription

- Early Phase: Emphasize passive joint mobilization and small-range active movements. Perform 2–3 times per day, each lasting 5–10 minutes, focusing on maintaining joint range of motion and preventing additional adhesions; at the same time, strengthen the shoulder girdle with mild isometric contractions to improve soft tissue condition.

- Intermediate Phase: As pain subsides and joint stability improves, gradually introduce low-resistance band exercises to strengthen the rotator cuff muscles (e.g., supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis). Increase frequency to about 3–4 times per week, each session lasting 15–20 minutes.

- Late Phase: If the condition and joint function allow, undertake full-range resisted exercises for the shoulder and aerobic activities (such as using an arm rowing machine) under professional supervision, 3–5 times per week, 20–30 minutes per session. Progressively increase exercise intensity. Monitor bone density and cardiopulmonary function closely to ensure safety.

- Fall Prevention and Other Safety Measures: Given the patient’s advanced age, pay special attention to environmental safety and load management to prevent recurrent falls and additional injury.

Disclaimer:

This report is based on radiological and clinical information and is intended for reference only. It should not replace in-person consultations or formal diagnoses and treatment plans from a qualified physician. Specific treatment and rehabilitation plans must be tailored to individual patient conditions and professional clinical evaluations.

Milwaukee shoulder syndrome