Calcific tendonitis of pectoralis major

Clinical History

A 53-year-old woman presented to our institution with several months history of spontaneous pain in the left upper arm; there was no history of trauma. Clinical examination revealed a restricted range of movement. The past medical history revealed malignant melanoma 10 years ago. Blood tests were normal.

Imaging Findings

An anteroposterior radiograph of the chest revealed a radiopaque image in the right humeral diaphysis (Fig. 1); this finding could be more precisely localized with a targeted examination, using a correct positioning with an oblique incidence.

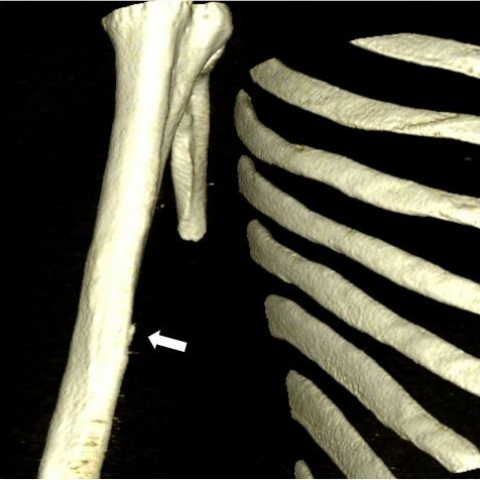

The patient underwent an MRI examination: on Fat-Sat T2-weighted sequences we observed an area of inhomogeneous high signal intensity, with ill-defined margins, in the bone marrow of the humeral diaphysis(Figs. 2-3) The imaging findings were suspect for bone neoplasm, and a CT examination was performed. Computed tomography revealed a calcification along the distal tendon of pectoralis major muscle, with associated minimal cortical erosion at its attachment (Figs. 4-5).

Discussion

Calcific tendonitis is a common disorder caused by calcium hydroxyapatite; it could involve any joint, however it typically affects the shoulder and the hip. The pathogenesis of calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition in a tendon is unclear. The most accredited theory is that calcific tendonitis is a primary disorder in susceptible tendons: it suggests the presence of a critical zone, whose poor oxygenation in certain circumstances can trigger a focal metaplasia, with transformation of the tendon into fibrocartilage and subsequent deposition of calcium [1].

The presentation is usually acute and symptoms may include erythema, swelling, painful range of motion and fever due to an inflammatory reaction. Although osseous involvement associated with calcific tendonitis has been reported, it is unusual despite the high incidence of calcific tendonitis [2].

Radiographic examination is usually necessary to diagnose calcific tendonitis, though tangential radiographs of the affected cortex are required to detect the calcifications and their association with cortical or marrow involvement. The “comet-tail” appearance of the calcifications [3] can help to confirm their intratendinous location.

CT achieves better results in detection of cortical erosion and soft-tissue calcification; CT should be considered as the preferred imaging modality to depict the continuity of the tendinous, cortical and medullary processes. MRI allows a more precise evaluation of the bone marrow involvement, but calcification in the adjacent tendon may not be appreciated, leading to the wrong concern of neoplasm.

Ultrasound can be useful to study calcific tendonitis; in our case the patient didn’t underwent an US evaluation because the diagnosis has been already achieved with other modalities.

The differential diagnosis of calcific tendonitis includes traumatic avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon and neoplastic processes, such as chondrosarcoma or other chondroid matrix producing neoplasm; the characteristic location of involvement in and near the major tendon attachments (usually easily detectable with US), as well as the lack of a discrete soft-tissue mass and the bilateral involvement by calcific tendonitis may be important observations in excluding neoplasm [2].

Treatment of calcific tendonitis is usually limited to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [4].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Calcific tendonitis of pectoralis major

Liscense

Figures

Radiographic examination

MR examination - Sagittal Plane

MR examination - Axial Plane

CT examination

3D surface-rendered reconstruction

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

1. Radiological Findings

Based on the provided X-ray, CT, and MRI images, the main findings are as follows:

- A localized abnormal density/signal is observed in the soft tissues near the proximal humeral metaphysis in the left upper arm, suggesting calcific lesions in the tendon or its attachment site.

- X-ray findings: A dense shadow, with relatively clear margins, is seen on the lateral proximal humerus. It may exhibit a “comet tail” appearance, indicating calcium salt deposition in the tendon or its attachment point.

- MRI findings: A localized signal abnormality in the corresponding area. On the T2-weighted sequence, there is mild indentation of the cortical bone or periosteal reaction, but no obvious soft tissue mass. Only mild changes in the bone marrow signal are noted, suggesting possible slight bone involvement or reactive bone marrow edema.

- CT findings: Local calcification and localized cortical erosion are further confirmed. The lesion is closely related to surrounding soft tissues and the tendon, with no obvious soft tissue mass.

Overall imaging findings are more consistent with calcific changes at the tendon or tendon attachment site. Although there is mild reactive bone change, there is no clear evidence of aggressive bone destruction.

2. Potential Diagnoses

Considering the patient’s history (a 53-year-old female with a history of malignant melanoma, currently presenting with left upper arm pain and normal blood tests) and the imaging findings, the possible diagnoses or differential diagnoses include:

- Calcific Tendonitis:

This is the most likely consideration. Lesions often occur in the shoulder tendons, with imaging showing localized calcium deposits within the tendon or at the attachment site, possibly appearing as clumps or with a “comet tail” sign. CT may show mild cortical changes or minimal bone marrow reaction, usually without a significant soft tissue mass. - Tumoral Lesion (e.g., Chondrosarcoma or Metastasis):

Given the patient’s history of malignant melanoma, metastasis or a primary chondrosarcoma must be excluded. Typically, malignant lesions demonstrate more pronounced bone destruction, soft tissue masses, and bone marrow infiltration. Current imaging does not reveal obvious signs of invasiveness or soft tissue masses, but it remains in the differential. - Tendon Avulsion Changes:

If there was trauma or avulsion at the tendon insertion, X-ray or CT might show bone fragments or local calcification. However, there is no clear history of trauma, and the pain appears spontaneously, which makes avulsive changes less likely.

3. Final Diagnosis

Taking into account the patient’s age, symptom characteristics (non-traumatic, chronic pain with restricted mobility), past medical history (despite melanoma, current blood tests and imaging show no obvious signs of malignancy), and the radiological findings (localized tendon calcification, mild cortical bone reaction, absence of a significant soft tissue mass or extensive bone destruction), the most likely diagnosis is:

Calcific Tendonitis.

If there is still concern, consideration may be given to monitoring lesion stability or performing a biopsy/puncture if necessary to rule out malignancy. However, based on the current information, a benign lesion is more strongly suggested.

4. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

According to the standard management principles of calcific tendonitis and the patient’s situation, possible treatment and rehabilitation plans are as follows:

- Conservative Treatment:

- Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to relieve pain and inflammation.

- During the acute inflammatory phase, short-term reduced activity or immobilization may be considered as needed.

- Physical therapy: Hot compresses, physiotherapy, and ultrasound therapy to help relieve local pain and promote resolution of inflammation.

- Injection Therapy (if applicable):

When conservative treatment is less effective and inflammation recurs, image-guided local corticosteroid injection or other minimally invasive interventions (e.g., shock wave therapy, needle aspiration/irrigation of the calcific deposit) may be considered to reduce inflammatory response. - Surgical Treatment:

For patients who do not respond to conservative measures or have large calcifications severely affecting function, surgical removal of the calcific deposit may be considered. However, most patients improve with systematic conservative treatment.

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription Recommendations:

- Early Phase (Acute Phase):

Frequency (F): 1–2 times per day with light activities

Intensity (I): Low intensity, avoid excessive pulling on the painful area

Time (T): 5–10 minutes each session, gradually increasing

Type (T): Passive or assisted range-of-motion exercises (e.g., gentle arm swings, finger wall-climbing)

Progression (P): Increase range of motion and frequency as pain subsides - Middle Phase (Repair Phase):

Frequency: Muscle strength and joint mobility exercises 3–4 times per week

Intensity: Moderate intensity, some resistance training (e.g., elastic band)

Time: 20–30 minutes each session, including local heat or physiotherapy

Type: Isometric exercises for the shoulder joint and upper limb muscles, gradually increasing load

Progression: Monitor range of motion and pain weekly, and increase training intensity accordingly - Late Phase (Functional Consolidation Phase):

Frequency: At least 3 times per week, can be incorporated into daily exercise

Intensity: Medium to high intensity, gradually increasing based on individual tolerance

Time: 30–45 minutes per session, including warm-up, core exercises, and cool-down

Type: Gradually return to normal activities and sports, possibly adding upper limb functional exercises (e.g., rowing machine, light resistance training)

Progression: Adjust intensity based on functional assessments to further strengthen or maintain training and prevent recurrence

Throughout the rehabilitation process, closely monitor the patient’s pain and functional improvement. If there is marked increase in pain or other discomfort, timely medical evaluation is necessary. For patients with fragile bones or insufficient cardiopulmonary function, exercise intensity should be individualized to ensure safety.

Disclaimer: This report is based on the analysis of current data and is provided for clinical reference only. It cannot replace an in-person consultation or the final opinion of a professional physician. Please combine the patient’s actual condition with professional advice for diagnosis and treatment.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Calcific tendonitis of pectoralis major