Brown tumours in regression mimicking sclerotic metastases

Clinical History

A 36-year-old patient with bilateral congenital renal dysplasia, currently on dialysis and on a waiting list for a kidney transplant presented to our institution as part of an assessment of a bacterial peritonitis secondary to peritoneal dialysis.

Imaging Findings

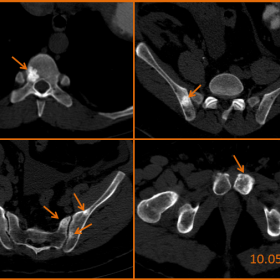

CT and conventional images showed multiple sclerotic, slightly heterogeneous lesions of the T9 vertebral body, pelvis and left femoral head, and one mixed lytic and sclerotic lesion of the left pubic body, that were not present on previous X-rays. In view of these newly formed lesions, bone metastases could be seen as a possible diagnosis; however, given the patient’s history of kidney transplant failure and his biological profile suggesting secondary hyperparathyroidism, brown tumours were the primary diagnosis. On MRI, the lesions were hypo-intense on all sequences (T2, T1, and STIR) except for the mixed lytic and sclerotic lesion of the left pubic body, which presented a heterogeneous increased signal intensity on T2 and STIR weighted images. Follow-up CT five months later showed absolute stability of all sclerotic lesions and sclerotic transformation of the mixed lesion of the left pubic body, solidifying the hypothesis of brown tumours in regression.

Discussion

The brown tumour is not an actual tumour but represents fibroblastic tissue containing numerous osteoclast-like giant cells. It can be seen at any age, in primary as well as secondary hyperparathyroidism. In chronic renal failure, excessive calcium urinary excretion leads to parathormone activation which in turn mobilises osteoclastic turnover of bone, with particularly rapid bone loss in some regions, which results in replacement of the bone marrow by reparative granulation tissue and vascular, fibrous tissue. The brown tumour lesions take their name from the presence of intra-lesional haemorrhagic elements and haemosiderin deposits in macroscopical analysis. They may also subsequently undergo necrosis and liquefaction, producing cysts [1].

On radiographs, brown tumours are well-defined osteolytic lesions, occasionally expansile and eccentric. On MRI, their appearance depends on the proportion of solid and cystic components; solid components are intermediate to low intensity on T1 and T2 weighted images, while cystic components are of high signal intensity on T2 weighted sequences; they may even present with fluid-fluid levels, mimicking aneurismal bone cysts; the solid components and septa enhance after gadolinium i.v. administration. [1, 2].

After resection of the adenoma or correction of the renal function, the osteolysis is replaced by osteosclerosis [3]. On MRI the signal intensity of the lesions on T1 and T2 weighted images, as well as their enhancement after contrast administration, regresses. In the absence of a sclerotic transformation other lesions, such as fibrous dysplasia, malignant tumours, or myeloma should be suspected.

Histological analysis does not always contribute to the diagnosis, as the findings are not specific and can be found in other bone lesions as well (such as giant cell tumours or granulomas and aneurismal bone cysts). Diagnosis is often based on follow up and on a spectrum of clinical, biological and radiological parameters [4].

Common locations of brown tumour lesions include the base of the skull, orbits, paranasal sinuses, spinal column, ribs, as well as pelvis, sacroiliac joints, femur, tibia, humerus, phalanges of the hand, clavicles and scapula, but it can also be seen in any bone of the body [5, 6].

Brown tumours may be asymptomatic or induce pain. Those localised in the spine may exceptionally be responsible for medullar compression [4].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Brown tumours in regression

Liscense

Figures

CT images in the axial plane without iv contrast medium

AP radiograph of the pelvis on 15.01.2010

AP radiograph of the pelvis on 06.12.2007

MRI T1 weighted and STIR weighted images

Comparison between abdominal CT on 10.05.2010 and 12.10.2010, without iv contrast medium

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

Based on the provided CT, X-ray, and MRI images, the following observations are noted:

- In the pelvis, proximal femur, and other areas, there are well-defined lytic or low-density lesions. Some lesions show mild expansile changes with locally visible thin residual cortical bone.

- On CT images, some lesions exhibit heterogeneous density with varying degrees of attenuation. On MRI, the solid components predominantly appear as low or isointense signals on T1- and T2-weighted images, while certain areas display hyperintense signals, suggesting possible cystic or liquefactive components.

- Some lesions present relatively well-defined boundaries, and after local contrast enhancement, solid septations or residual trabeculae can be observed.

- No obvious fractures are identified, but the lesions are fairly extensive, indicating a larger scope of skeletal involvement that necessitates consideration of systemic factors.

II. Potential Diagnoses

Taking into account the patient’s medical history (bilateral congenital renal dysplasia, long-term dialysis, high risk of secondary hyperparathyroidism) and the imaging features, the following diagnoses or differential diagnoses can be considered:

- Brown Tumor or bone lesions due to secondary hyperparathyroidism:

In this case, the patient has chronic renal failure and suspected secondary hyperparathyroidism. Brown tumors typically appear as expansile lytic lesions with variable signal intensity, often affecting multiple bones throughout the body. - Giant Cell Tumor of Bone:

Often located in the epiphyseal-metaphyseal region, presenting as lytic lesions that can be multiloculated or cystic. However, given the patient’s age, multiple lesions, and systemic condition, an expansile lesion such as a Brown tumor is more likely. - Fibrous Dysplasia:

Can show a “ground-glass” appearance, but widespread bone destruction in the context of renal insufficiency is less commonly attributed to this condition. - Other malignant lesions (e.g., metastatic tumors or multiple myeloma):

Commonly present with extensive lytic changes or abnormal densities. However, correlation with PTH levels, calcium-phosphorus metabolism markers, and MRI characteristics can help distinguish them from Brown tumors.

III. Most Likely Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s background of chronic renal failure, long-term dialysis, possible secondary hyperparathyroidism, along with multiple lytic lesions in imaging, some showing an expansile nature, heterogeneous signal, and post-contrast solid septations, the most fitting diagnosis is: Brown Tumor caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism.

For further confirmation, assessment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, serum calcium and phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, and possibly histopathological examination (to rule out malignancy) can be considered.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

1. Treatment Strategy

For bone changes caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism, the main therapeutic goals are to control excessive PTH secretion and correct calcium-phosphorus imbalance:

- Medical Management: Includes correcting disturbances in serum calcium and phosphorus, utilizing active vitamin D or calcium modulators (such as calcium supplements and phosphate binders), and if necessary, medically suppressing parathyroid activity.

- Surgical Treatment: Parathyroidectomy may be considered if there is significant parathyroid gland hyperplasia or adenoma. In cases of severe bone destruction or neurological compromise (e.g., spinal cord compression), lesion curettage or decompression surgery may be performed.

- Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation: Maintaining adequate and regular dialysis is essential, and evaluating for kidney transplantation could be pursued to fundamentally improve renal function, thereby alleviating secondary hyperparathyroidism.

2. Rehabilitation/Exercise Prescription

With ongoing skeletal involvement and increased bone fragility, a gradual and individualized approach is recommended:

- Frequency: Low-impact aerobic and resistance training can be performed 2-3 times per week.

- Intensity: Begin with low-intensity exercise (for instance, target heart rate at 40-50% of maximum). Avoid high-impact activities and start with non-weight-bearing or low-weight-bearing exercises, such as walking on level ground or using a stationary bicycle.

- Time: Each session can last 15-30 minutes, increasing gradually based on tolerance.

- Type: Joint-friendly activities (swimming, elliptical machine, light resistance exercises) are preferred. Avoid high-load or heavy-resistance training.

- Volume & Progression: As bone health and overall condition improve, incrementally increase session duration and introduce light loads. This should be done under supervision by a specialist or rehabilitation therapist to minimize fracture risk.

Throughout rehabilitation and exercise, closely monitor the patient’s symptoms. In the event of significant bone pain or discomfort, exercise should be stopped and reassessed. Long-term follow-up of bone density and PTH levels is recommended to adjust treatment and exercise prescriptions.

Disclaimer

This report is based on the current imaging findings and medical history and serves only as a reference. It does not replace an in-person clinical diagnosis or professional medical advice. If there are any questions or changes in condition, please consult with the appropriate specialist promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Brown tumours in regression