Acute idiopathic necrotizing fasciitis of the chest wall: a case report

Clinical History

A 42-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department at 3:00 a.m. with malaise and right-sided intense chest pain that had occurred during the night. He denied experiencing trauma or recent surgical procedures. His medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, mild chronic renal failure and Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Imaging Findings

Physical examination revealed fever (38.0°C) with normal vital signs.

Laboratory studies showed leukocytosis, high CRP and serum creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL.

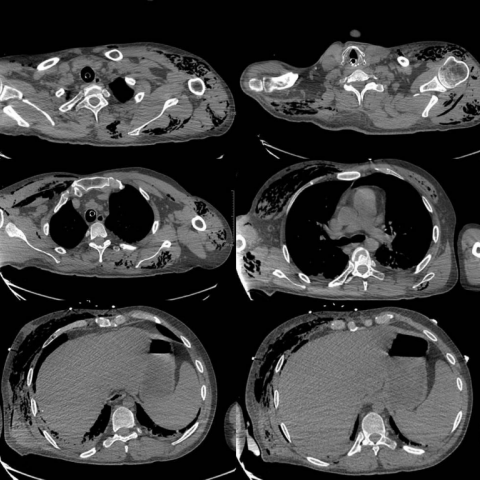

Chest CT performed at 4:17a.m. excluded the presence of pneumonia, but showed gas collection in the right pectoralis major muscle with thickening of its fascial planes and increased attenuation of the subcutaneous fat tissue suggesting oedema.

The patient was immediately treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics for a suspected soft-tissue infection but his clinical conditions worsened rapidly: chest pain increased, overlying skin became mottled, swollen and warm. The patient became tachycardic and dyspnoeic.

At 8:00a.m., he developed a severe shock condition requiring intubation and intensive cares.

At 8:32a.m. another CT examination showed the extension of the muscular involvement in the chest wall and the shoulder girdles with massive air collection due to the extensive gas gangrene, associated with intramuscular and subcutaneous fluid collection.

Shortly after the patient died in the ICU.

Discussion

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rare, life-threatening infection of any layers within the soft tissue compartment (dermis, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, deep fascia and muscle), that progresses rapidly through the fascial planes causing necrosis and destruction of the affected tissues. It is relatively uncommon, with a global prevalence reported to be about 4 cases per 1,000,000 population [1]. It affects all age groups, although it is more frequent in elderly patients, with a M/F ratio of 3:1 and a mortality estimated to be 21.5% [2, 3]. However, without treatment, the mortality reaches 100%. Most common localizations are lower extremities followed by the abdomen and the perineum (Fournier’s gangrene). Upper limbs and trunk are rarely involved.

Patients often have a history of trauma, including external injuries or surgical wounds. Common co-morbidities include diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, chronic heart failure, renal failure, cancer, immunodeficiency and alcohol abuse [3].

The most common type of NF is a polymicrobial infection with both aerobic and anaerobic gas-forming bacteria (Clostridium, Proteus, Enterobacteriaceae) [3].

NF can be difficult to recognize in its early stages. The clinical presentation is often non-specific and causes delay in diagnosis: fever, malaise, tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension. Local symptoms and signs include: pain (typically disproportionate to the clinical findings), swelling and erythema of the overlying skin; in the advanced stages it evolves to skin ischaemia with bullae and blisters. In the fulminant form it presents with septic shock and multi-organ failure.

This challenging diagnosis may be facilitated by radiology. Plain radiography has low sensitivity and specificity, but is capable to show gas formation in soft tissues [4].

CT can play a vital role in suggesting the right diagnosis rapidly. The rapidity of CT compared with MRI may be advantageous for an emergent necrotizing fasciitis evaluation. The CT hallmarks are: thickening of nonenhancing fascial layers indicative of NF, air and fluid collection in soft tissues, muscular and fat stranding [5, 6]. CT also shows reactive lymphadenopathy, underlying infection sources and complications of tissue necrosis like vascular rupture [6, 7].

MRI is the modality of choice for detailed evaluation of soft-tissue infection with fluid collection and fascial thickening, but is often not performed for necrotizing fasciitis evaluation because its acquisition is time-consuming and will delay treatment [8].

Prompt diagnosis is mandatory to permit emergency surgical debridement, necrosectomy and fasciotomy of the affected tissues. Surgical intervention is life-saving and must be performed as early as possible. Patients should also be immediately treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics when NF is suspected.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Necrotizing fasciitis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

CT axial plane

CT sagittal plane

CT axial plane

CT axial plane

CT sagittal plane

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

Based on the provided chest CT images, there is notable swelling of the right chest wall soft tissue. Gas density is observed within the subcutaneous fat and between muscle fascia (presenting as low density with foci of gas density), suggesting infectious gas accumulation. In some areas, the fascia appears significantly thickened with uneven enhancement and obvious fat stranding, indicating local edema or exudation.

No obvious signs of substantial parenchymal lesions are seen in the lung fields. The mediastinal structures are relatively midline, though some lymph node enlargement is noted locally. No clear bone destruction or fracture is observed. Overall imaging characteristics are consistent with a rapidly invasive infection of the soft tissue and fascial layers, producing gas.

II. Potential Diagnoses

- 1. Necrotizing Fasciitis (NF)

Due to the presence of gas formation, fascial swelling/thickening, widespread soft tissue involvement, and multiple comorbidities (diabetes, chronic renal failure, malignancy, etc.) as risk factors, this diagnosis should be the primary consideration. - 2. Deep Soft Tissue Abscess or Cellulitis with Gas Formation

While cellulitis can present with subcutaneous gas, typical necrotizing fasciitis progresses more rapidly, often involving fascial layers and producing more gas. A limited gas pocket with abscess formation should be considered, but in this case, the involvement of multiple fascial layers strongly suggests necrotizing fasciitis. - 3. Other Rare Soft Tissue Infections or Chest Wall Gas Gangrene

For instance, infections caused by gas-forming Clostridium species may present more explosively and with larger areas of involvement, often with a history of severe trauma or surgery. Although this patient has no clear history of trauma, it still needs to be included in the differential diagnosis.

III. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s sudden onset of severe chest pain during the night, previous comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, lymphoma resulting in immunocompromised status), and the CT findings of chest wall fascial involvement with apparent gas formation, the most likely diagnosis is: Necrotizing Fasciitis (chest wall involvement).

Given the aggressive course of this disease and its high mortality rate, laboratory results (e.g., white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, lactate level) and possible microbiological testing should be performed promptly to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment as soon as possible. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, further MRI evaluation may be considered, or pathological evidence should be obtained during surgical exploration.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Strategy

- Emergency Surgical Intervention:

The primary treatment for necrotizing fasciitis is early and thorough surgical debridement and removal of necrotic tissue. This should be performed as quickly as possible to prevent the spread of infection and avert further systemic infection and sepsis. - Antibiotic Therapy:

Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics early (covering both aerobic and anaerobic organisms). Dynamic adjustments to the therapeutic regimen should be made according to the patient’s culture results. - Supportive Treatment:

Closely monitor vital signs and organ function; correct fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances. For patients with diabetes, chronic renal failure, or other underlying diseases, actively control blood glucose, monitor renal function, and consider necessary renal replacement therapies. - Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (Optional):

In patients with gas-producing anaerobic infections or severe vascular compromise, hyperbaric oxygen therapy can help improve local oxygen supply and promote tissue repair.

2. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription

Principle: Because necrotizing fasciitis often requires extensive surgical debridement, the early stage focuses on wound healing and functional maintenance, the mid-stage on preventing muscle strength loss and joint range-of-motion limitations, and the late stage on rebuilding physical fitness and daily activity capacity. An individualized plan should be developed according to the patient’s overall condition, cardiopulmonary function, and the progression of surgical wound healing. The following is a brief phase-based example using the FITT-VP principle:

-

Acute Recovery Phase (Early Postoperative):

- Frequency: 2–3 times per day of light activity (e.g., changing position in bed, deep breathing exercises, gentle upper or lower limb movements).

- Intensity: Extremely low, ensuring no provocation of wound pain or undue fatigue.

- Time: About 5–10 minutes of gentle movement each session.

- Type: Primarily active joint movements, fist opening and closing, ankle rotations, and other simple exercises.

- Progression: As wound healing and overall tolerance improve, gradually increase the range and frequency of joint movement.

-

Functional Improvement Phase (From Wound Stabilization to Several Weeks Post-Op):

- Frequency: 3–4 days per week, with appropriate rest intervals.

- Intensity: Low to moderate, with heart rate controlled at 40%–50% of maximum heart rate (if cardiovascular function permits).

- Time: 15–20 minutes per session initially, slowly extending up to 30 minutes.

- Type: Gradually increase lower limb cycling, basic upper limb strength training (using resistance bands or light weights), and breathing exercises.

- Progression: Increase intensity or duration as body endurance and wound healing improve.

-

Strengthening and Consolidation Phase (Long-Term Rehabilitation):

- Frequency: 3–5 times per week.

- Intensity: Moderate, depending on the patient’s tolerance and cardiopulmonary function.

- Time: 30–45 minutes each session, combining aerobic exercise and strength training.

- Type: May include brisk walking, swimming (once the wound has healed), or other low-impact aerobic exercises, as well as core training.

- Progression: Under the guidance of rehabilitation specialists or physicians, gradually transition to daily physical activities or occupational functional training.

If the patient has limited cardiopulmonary function or other chronic diseases (e.g., renal insufficiency), exercise volume and approach should be further adjusted under guidance from cardiology or relevant specialists to ensure safety.

Disclaimer: This report is solely a reference analysis based on the provided information. It is not a substitute for in-person consultation or professional medical diagnosis and treatment. If you have any concerns, please consult a specialist promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Necrotizing fasciitis