Unstable L1 fracture in ankylosing spondylitis

Clinical History

The patient was admitted to the emergency department due to lumbar back pain after a fall from standing height. The physical examination found that the abdomen was distended. No neurological defects were present. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdomen was performed.

Imaging Findings

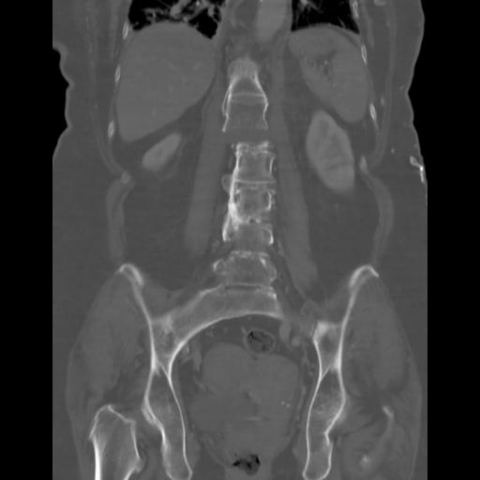

The thoracic and lumbar spine showed severe changes associated with ankylosing spondylitis (AS). These changes included ankylosis between vertebrae resulting in a “bamboo spine” (Figures 1-2). Furthermore an unstable transverse fracture (extension type fracture) through the L1 vertebrae was seen (Figures 1-2). All three columns through the L1 vertebrae were fractured with an outcome angulation of 15 degrees (Figure 1). No other acute findings were present in the chest or abdomen. An acute MRI was suggested to further evaluate the spinal cords relation to the fracture. However, the patient was unable to cooperate in this procedure.

Discussion

AS is a progressive and chronic inflammatory condition, predominantly affecting the spine and the sacroiliac joints. In the later stages of the disease it is characterized by osteoporosis and syndesmophyte formation. Subsequent bridging of these syndesmophytes leads to ankylosis and the radiographic feature “bamboo spine”. These pathological transformations predispose AS patients to spinal fractures even after low energy trauma [1], such as a fall from standing height. The prevalence of spinal fractures in AS patients has been estimated to range from 4-18 % [2] with a four-fold lifetime risk compared to the background population [3]. Cervical fractures (81%) are the most common spinal fractures in patients with AS followed by fractures at the thoracic (11%) and lumbar spine (8%) [4]. Spinal fractures in AS patients are often unstable and can result in neurological injury.

AS patients using conventional X-ray can be challenging. This is due to the distorted anatomy caused by AS at the affected site of the fracture, and in the worst-case scenario a spinal fracture can go unnoticed [5]. A report showed that 42 % of AS patients with a spinal fracture did not initially receive the correct diagnosis of the fracture, which led to secondary neurological complications in 17 % these patients [6]. Cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI should therefore be prioritized when suspecting a spinal fracture in a patient with AS. A study examining 20 AS patients with suspected spinal fractures showed that CT was able to detect six spinal fractures not seen on MRI, and vice versa MRI detected two spinal fractures not seen on CT [7]. On the other hand, MRI is more sensitive at detecting spinal cord compression, paravertebral haemorrhages and soft tissue abnormalities.

The present case illustrates a severe lumbar spine fracture in an AS patient. It underlines the fact that low energy trauma may result in disproportionate damage in this patient group with altered biodynamic strength of the vertebral column. Following imaging, internal fixation across the fracture was performed. No neurological deficits occurred.

In conclusion, patients with known AS admitted after low energy trauma should be imaged to rule out a spinal fracture. Cross-sectional imaging with either CT or MRI should be performed [8].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Unstable L1 fracture in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Enhanced CT sagittal

Enhanced CT coronal

Medical Analysis Report

1. Imaging Findings

Based on the contrast-enhanced CT images provided, the lumbar vertebrae show obvious vertebral shape variations accompanied by the formation of bony bridges (syndesmophytes), consistent with late-stage radiological findings of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS). A part of the lumbar vertebral body appears locally collapsed, and a clear fracture line can be observed, indicating a lumbar vertebral fracture. The surrounding soft tissue density shows local swelling, but there is no significant large-scale soft tissue hematoma expansion or evidence of nerve root compression. Meanwhile, the adjacent intervertebral disc regions appear disordered, implying deformities of the vertebral segments due to prolonged AS involvement.

2. Possible Diagnoses

- Ankylosing Spondylitis with Lumbar Fracture: The patient has a known history of AS. Following a low-energy trauma, radiological findings now suggest a local fracture in the lumbar region, aligning with the tendency of patients with this disease to sustain fragility fractures.

- Osteoporosis-Related Fracture: Osteoporosis is common in elderly women, and limited activity due to AS can further exacerbate loss of bone density. Therefore, an osteoporotic compression or burst fracture should also be considered.

- Other Pathological Fractures (Rare): For example, fractures caused by tumors or metastatic lesions. However, at present, no typical signs of tumor or bony destruction are seen on imaging, so this remains only a differential diagnosis.

3. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s advanced age, history of AS, the low-energy injury, and the clear lumbar fracture line and ankylosis observed on imaging, the most likely diagnosis is Ankylosing Spondylitis with Lumbar Vertebral Fracture. Currently, there is no evident nerve compression or substantial soft tissue hemorrhage, but close monitoring and follow-up are necessary. MRI may be needed to clarify the status of the spinal cord and nerve roots if clinically indicated.

4. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

4.1 Treatment Strategies

- Surgical Fixation: Because AS increases spinal rigidity and predisposes to unstable fractures, internal fixation surgery can be considered for unstable or displaced fractures to maintain vertebral stability and prevent secondary injuries and nerve complications.

- Conservative Treatment: For milder, stable fractures or in patients with high surgical risks, options include bracing and bed rest, combined with analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications. Dynamic observation of fracture healing is also necessary.

- Pharmacological Intervention:

- Anti-osteoporosis medications: Such as bisphosphonates, vitamin D, and calcium supplements to protect bone mass.

- Basic therapy for AS: If the disease is active, NSAIDs can be used, or biological agents (e.g., TNF-α inhibitors) may be considered based on the level of inflammatory activity.

- Pain Management: If needed, use patient-controlled analgesia pumps or oral/topical analgesics, etc.

4.2 Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription

Rehabilitation training can begin gradually once the fracture is stabilized and firmly fixed surgically, or once conservative treatment has achieved relative stability. A general plan is as follows:

- Early Stage (Postoperative or Acute Phase): Focus on bed-based limb activity and breathing exercises, avoiding excessive weight-bearing or twisting:

- Frequency: 2-3 times per day

- Intensity: Mild, without causing evident pain or fatigue

- Duration: Approximately 10-15 minutes each session

- Method: Perform ankle pump exercises, isometric quadriceps contractions, gentle active upper body movement on the bed, and deep breathing exercises

- Mid Stage (After Partial Fracture Healing): Gradually increase lumbar and back muscle training and light resistance exercises, under bracing or professional protection:

- Frequency: 3-4 times per week

- Intensity: Low to moderate, based on the patient’s tolerance

- Duration: 20-30 minutes each session, in segments

- Method: Simple lumbar stabilization exercises near the bed or in a stable environment, such as pelvic bridge exercises (under the guidance of a physician or physical therapist) and lower extremity strength exercises (e.g., straight leg raises)

- Late Stage (After Solid Fracture Healing): Undertake core muscle training and aerobic exercise (e.g., cycling, swimming) under professional guidance to improve overall function and cardiopulmonary endurance:

- Frequency: 3-5 times per week

- Intensity: Moderate, with a suitable increase in heart rate without excessive fatigue

- Duration: 30 minutes or longer, gradually increased

- Method: Elliptical trainer workouts, water-based floating exercises with minimal impact on the spine, and flexibility exercises such as stretching and joint range-of-motion sessions under professional supervision

Throughout the rehabilitation process, emphasis should be placed on:

- Appropriate use of protective braces or lumbar supports

- A gradual approach, avoiding a sudden increase in exercise intensity

- Vigilant monitoring of symptoms; if pain worsens or new neurological symptoms emerge, seek medical attention promptly

Disclaimer: This report is only a reference analysis based on the existing medical history and radiological materials. It cannot replace in-person consultation or the individualized advice of professional healthcare providers. Patients should follow the guidance of specialized physicians and undergo further examination to confirm their final treatment plan.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Unstable L1 fracture in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis