A 73-year-old man was referred to the internal medicine department. His complaints were lifelessness and physical deconditioning since one and a half year. Laboratory results showed microcytic anaemia and raised inflammatory markers. A gastroscopy, colonoscopy and bone marrow aspiration could not reveal any suspicious findings. 18FDG-PET/CT imaging was performed.

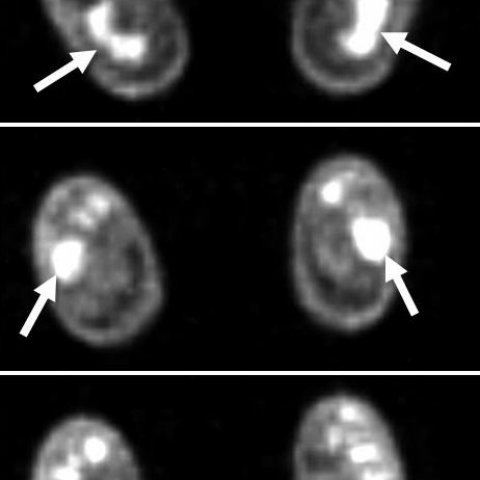

CT imaging of the legs shows medullar osteosclerosis with cortical thickening, affecting the diaphysis and metaphysis. High FDG uptake in the corresponding areas on 18FDG-PET imaging (1a, b). CT imaging of thorax and abdomen shows soft tissue infiltration around the aorta (2a-e), expanding into the left and right paravertebral space (2a-c). Note the retrosternal (2a) and pleural soft tissue infiltration (2b). The adrenal glands are swollen with soft tissue infiltration of the adjacent fat. Increased FDG tracer uptake in the adrenal glands, around the aorta and in the stomach (2d). Soft tissue infiltration in the left and right perirenal and posterior pararenal space (‘hairy kidney’ sign), expanding into the renal sinuses (2e). A left-sided hypermetabolic spot anterior to the middle cerebral artery and a high FDG tracer uptake in the small bones of the feet on 18FDG-PET imaging, with no corresponding lesions on CT imaging (3a, b).

Erdheim-Chester Disease (ECD) is a rare multisystemic disease of unknown aetiology [1, 2]. It is characterized by a typical pattern of osseous infiltration and a varying degree of extraskeletal involvement [3, 4]. Most frequent symptoms are bone pain, diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos, renovascular hypertension or neurological manifestations [4-6].

Osseous infiltration generally consists of a symmetric bilateral osteosclerosis in the metaphysis and diaphysis of the long bones [2, 3, 5]. Other radiographic features are osteolysis, cortical thickening, narrowing of the medullar cavity, a blurred corticomedullary margin, a metaphyseal radiolucent band and signs of periostitis. On MR imaging, osteosclerosis is hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images; enhancing after gadolinium injection [3].

Bilateral soft tissue infiltration of the perirenal and posterior pararenal space is called the ‘hairy kidney’ sign. This sign consists of a homogeneous band with spiculated contours, hypoattenuating on CT imaging and isointense to muscle on T1 and T2 weighted MR imaging [2, 4]. Infiltration can expand into the adrenal fossa [4, 5]. Diffuse circumferential involvement of the aorta is called the ‘coated aorta’, hypo-attenuating on CT imaging and isointense to muscle on T1- and T2-weighted images [2, 4]. Cardiac involvement manifests as pericardiac soft tissue thickening, pericardiac effusion or a myocardial pseudo-tumorous mass. On high resolution CT imaging smooth septal thickening, centrilobular nodules or pleural thickening can be seen [2, 4, 5]. Retro-orbital soft tissue involvement is usually intraconal, bilateral and lacks signal intensity on T1 and T2 weighted MR imaging. Hypothalamic-pituitary axis involvement appears on T1 weighted MR imaging as a nodular mass in the pituitary stalk or an absence of signal in the posterior pituitary [5]. Neurological involvement can manifest as nodules or mass lesions in the brain, the meninges or the spinal cord with an increased signal intensity on T2 weighted MR imaging and prolonged enhancement after gadolinium injection on T1 weighted MR imaging [6, 7].

99mTc bone scintigraphy and 18FDG-PET/CT imaging have the advantage of performing a whole-body examination [3, 8]. 99mTc bone scintigraphy will demonstrate an increased tracer uptake in all bony lesions and can detect radiographically silent bone involvement [3]. 18FDG-PET/CT imaging demonstrates a high FDG uptake in all metabolically active lesions [8].

Diagnosis of ECD is suspected on imaging findings and confirmed by histological analysis of a biopsy. Globally, prognosis is poor and therapeutic options are scarce. Medical treatment includes corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, cytotoxic agents and immunosuppressive drugs [2, 5]. Surgical intervention is indicated when a mass compresses the brainstem or the spinal cord [6].

Diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester Disease was confirmed on a bone biopsy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The patient is a 73-year-old male presenting with fatigue and general decline in physical function for one and a half years. Hematologic tests indicate microcytic anemia and elevated inflammatory markers. Gastrointestinal endoscopy and bone marrow aspiration show no obvious abnormalities. After whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT and corresponding CT examinations, the imaging reveals the following main features:

1. Symmetrical sclerotic changes in the metaphysis/epiphysis of bilateral long bones (tibias, femurs), with thickened cortical bone in some regions and possible narrowing of the medullary cavity.

2. On bone scans or PET/CT, the skeletal lesions exhibit high metabolic activity.

3. In soft tissues, band-like areas of infiltration surrounding major blood vessels (e.g., heart sac, around the aorta), resembling the “coated aorta” sign.

4. Band-like soft tissue densities around both kidneys, resembling the “hairy kidney” sign.

5. Some patients may show pituitary stalk abnormalities or intracranial (e.g., sellar region, meninges) lesions, with mild to moderate radiotracer uptake on PET/CT.

These findings suggest a typical systemic process of tissue proliferation and infiltration, and the involvement of multiple bones and soft tissues simultaneously indicates a systemic disease.

Combining the imaging findings with the patient’s clinical history, possible diagnoses include but are not limited to:

1. Erdheim-Chester Disease (ECD): A rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorder. Typical imaging features include symmetrical sclerotic long-bone lesions, the “coated aorta” sign, the “hairy kidney” sign, and multisystem involvement.

2. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH): Also a histiocytic disorder but more often involves the skull, lungs, and skin, and is more common in younger patients.

3. Multiple Myeloma: Usually shows lytic or mixed bone lesions, often accompanied by bone pain, anemia, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction. In this case, sclerotic lesions predominate, and the cold (or hot) lesion pattern does not fully match multiple myeloma.

4. Metabolic Sclerotic Bone Diseases (e.g., severe osteosclerosis): Generally, these do not exhibit significant soft tissue or visceral infiltration, and they lack markedly elevated inflammatory markers or renal impairment.

Based on the overall analysis, Erdheim-Chester Disease is the most characteristic diagnosis, while other possibilities require exclusion through histopathology or further clinical evidence.

After integrating the patient’s age, symptoms, imaging findings, and the exclusion of other common conditions, Erdheim-Chester Disease (ECD) is the most likely diagnosis.

Since a definitive diagnosis of ECD typically requires pathological confirmation (e.g., biopsy of bone lesions or involved soft tissue lesions), it is recommended to arrange a biopsy or surgical sampling as soon as possible to obtain histological evidence. If histopathological confirmation has already been obtained, then ECD can be definitively diagnosed.

Treatment for Erdheim-Chester Disease generally includes the following aspects:

1. Pharmacological Treatment:

- Glucocorticoids: Commonly used to control inflammatory processes and alleviate symptoms;

- Bisphosphonates: Help control bone lesions and relieve bone pain;

- Immunosuppressants or Cytotoxic Drugs: May be used when the disease progresses rapidly or there is severe involvement of vital organs;

- Interferon or Other Targeted Therapies: Some case reports show certain efficacy with these agents.

2. Surgical/Interventional Treatment:

For lesions that are life-threatening or causing severe compression (e.g., spinal cord or brainstem compression), decompression surgery or lesion removal can be considered. Radiotherapy may be used adjunctively if necessary.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Guidance:

- Rehabilitation Principles: ECD patients often experience bone changes, cardiorespiratory compromise, and systemic fatigue. An individualized, gradual exercise prescription is recommended;

- Forms of Exercise: Low-impact aerobic exercises (e.g., walking, stationary cycling, swimming) and low-resistance training (using light dumbbells or resistance bands);

- FITT-VP Principles Example:

• Frequency: 3–5 times per week;

• Intensity: Low to moderate intensity according to the patient’s perceived exertion (feasible for heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing);

• Time: About 20–30 minutes of aerobic exercise per session; 8–12 repetitions of resistance exercise for 2–3 sets;

• Type: Alternate between aerobic training and light resistance training;

• Progression: Closely monitor the patient’s tolerance to exercise load and gradually increase training duration or slightly increase resistance;

• Volume & Progression: Adjust goals in stages based on daily functional improvement and subjective feedback.

- Precautions: Avoid high-impact, excessive weight-bearing activities or those with a high risk of fracture. If significant bone pain, shortness of breath, or abnormal heart rate occurs, reduce intensity or pause the exercise and seek timely evaluation.

Disclaimer:

This report is based on the provided imaging and clinical information, and is intended for reference purposes only. It does not replace in-person consultation or professional medical advice. Specific diagnoses and treatment plans should be determined by a specialist after a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s actual condition.

Diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester Disease was confirmed on a bone biopsy.