The co- existence of the innocent and the guilty: Sever's apophysitis and Eosinophilic Granuloma.

Clinical History

A 10-year-old child presented in the Child Health department with thoracic pain and mobility reduction of the right leg. The clinical and the laboratory examination revealed leukocytosis and eoshinophilia while the x-rays of the thoracic spine showed sphenoid distortion of the 8th vertebra without history of trauma (Fig1).

Imaging Findings

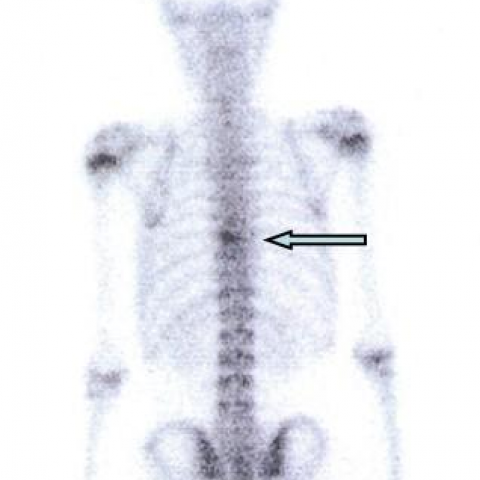

MRI of the thoracic spine was performed for further investigation. The 8th thoracic vertebra showed height loss with sphenoid distortion and pathologic signal (hypointense in T1, hyperintense in T2 and STIR- weighted images). Furthermore, there was a small amount of pathologic para-vertebral tissue. After intravenous gadolinium administration the 8th vertebra and the tissue showed markedly enhancement (Fig.2, 3). The imaging findings were compatible with "eosinophilic granuloma". The second step was bone scintigraphy in order to confirm the diagnosis by excluding other bone lesions. The bone scintigraphy showed increased radionuclide uptake of the 8th thoracic vertebra and the right calcaneus (Fig.4, 5). MRI examination of the right ankle was performed and demonstrated fragmentation and bone edema of the secondary ossification core of the right calcaneus, findings similar with "Sever's apophysitis" (Fig.6, 7).

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) or histiocytosis X is characterized histologically, by a proliferation of dendritic cells resembling normal Langerhans cells. Clinical manifestations can vary from an isolated, non-progressive bony lesion (eosinophilic granuloma) to rapidly progressive multisystem involvement (Letterer-Siwe disease). LCH is not a neoplasm; it should be considered a proliferative lesion, possibly secondary to a defect in immunoregulation, producing destructive effects on the tissues in which such proliferation occurs. More than half of the patients younger than 2 years with disseminated LCH die of the disease, whereas unifocal LCH is usually self-limited. Age of onset varies according to the variety of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease occurs predominantly in children younger than 2 years while localized eosinophilic granuloma(EG) occurs mostly frequently in 5-15 years. EG involves calvarium, ribs, mandible, long bones and spine. The classical lesion of the spine is the "vertebra plana". It consists of flattening of one vertebral body, with close apposition of the unaffected intervertebral disks. The residual vertebra is hypointense in T1-weighted images, hyperintense in T2-weighted images and enhances markedly with gadolinium injection. Sometimes there is extension of pathologic tissue to the ventral epidural space [1-3].

"Sever's apophysitis" in children is a self-limited situation related to an active growth spurt during 7-15 years of age, with male predominance. Furthermore, it is a common injury in young athletes, caused by running, jumping or repetitive microtraumas. The calcaneus bone contains both physeal and apophsyseal hyaline cartilage. The secondary ossification centre develops within this cartilage, usually with a multifocal appearance, duplicating the chondro-osseous transformation. Any type of injury can prevent this process which involves trabecular remodelling of primary and secondary spongiosa of metaphysis. Thus, the ossified nucleus appears with an increased fragmentation (reflecting mechanic demands during vulnerable periods) in children with Sever's apophysitis unlike the healthy population. MRI plays a significant role in the diagnostic procedure, showing the edematous changes within the calcaneal apophysis, possibly extending into the neighbour tuberosity. Plain radiography, ultrasonography and scintigraphy can exclude types of fractures and teninditis/ bursitis respectively. Differential diagnosis includes infectious or traumatic causes. Patients with calcaneous apophysitis do not have growth disturbance, so a repair process is not required. Common advice is rest and activity reduction [4-6].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Eosinophilic Granuloma and Sever's apophysitis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

MRI SPINE-T2 & STIR sagittal

MRI SPINE-T1 & T1-Gd sagittal

Bone scintigraphy 1

Bone scintigraphy 2

MRI-STIR & T1 sagittal

MRI T1 & T1-Gd sagittal

X-ray spine

Imaging Findings

The patient is a 10-year-old boy, presenting with thoracic spine pain and restricted movement in the right leg. Thoracic spine X-ray and MRI show an abnormal morphology of the T8 vertebral body, which appears significantly flattened (vertebra plana), with no marked involvement of the adjacent intervertebral spaces. MRI reveals abnormal signal within the T8 vertebral body, appearing hypo- to isointense on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images, and showing prominent enhancement after gadolinium administration. There is a small amount of soft tissue swelling or infiltration in the adjacent soft tissues or epidural space. Laboratory tests show leukocytosis and eosinophilia. No obvious history of trauma was noted.

Potential Diagnoses

-

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH, also known as Eosinophilic Granuloma):

Rationale: The patient’s age fits the common age range (5–15 years), imaging demonstrates vertebra plana, and there is eosinophilia. This condition is a proliferative lesion that can be mono- or multifocal, causing vertebral body destruction and collapse. On imaging, the vertebral body height is markedly reduced, yet the intervertebral discs are relatively preserved. -

Vertebral Tuberculosis or Bacterial Infectious Spondylitis:

Rationale: Vertebral destruction can also be seen in infections; however, it is often accompanied by intervertebral disc destruction and clinical signs of infection (such as high fever, progressive pain). Although there is leukocytosis in this patient, there are no typical signs of disc involvement or obvious abscess formation. Eosinophilia is more suggestive of LCH. -

Metastatic Lesions or Other Bone Tumors:

Rationale: Malignant tumors can cause vertebral destruction. However, spinal metastases in a 10-year-old child would necessitate ruling out a primary malignancy. Imaging of “vertebral compression” is often accompanied by varying degrees of soft tissue mass. Eosinophilia is not commonly associated with malignancies.

Final Diagnosis

Combining the patient’s age, clinical symptoms (thoracic spine pain, restricted movement), lab results (leukocytosis, eosinophilia), and imaging findings (vertebra plana), the most likely diagnosis is

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (monostotic eosinophilic granuloma).

If further confirmation is needed, a biopsy of the vertebral lesion can be performed to obtain histological and immunohistochemical evidence (e.g., CD1a, S-100 protein).

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

For monostotic Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, conservative and localized treatments are usually the primary approach. If the condition is stable with no neurological compression, observation or appropriate bracing can be considered, along with analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications. If necessary, curettage of the lesion or local injections (e.g., steroids) may be performed.

1. Conservative Management and Follow-up

- Use of a brace to avoid excessive spinal load, aiming to alleviate pain and prevent further collapse.

- Regular imaging follow-up to monitor lesion progression and determine if additional interventions are needed.

- Emphasize adequate nutrition, ensuring sufficient intake of vitamin D and calcium for bone healing and growth.

2. Rehabilitation Training Principles (FITT-VP)

- Frequency: 2–3 times per week; focus on low-impact exercises, avoiding intense shaking or impact.

- Intensity: Begin with low-intensity exercises (e.g., low-impact core training, lower limb strengthening) and gradually adjust according to symptom improvement.

- Time: Start with 10–15 minutes per session, progressively increasing to 20–30 minutes, ensuring no exacerbation of pain or fatigue.

- Type: Activities such as swimming, gentle stretching exercises, lower limb and core muscle training, all aiming to minimize excessive spinal load or violent impact.

- Progression: Increase training difficulty as the body recovers, progressing from basic core stabilization to light-weight bearing exercises for upper and lower limbs. If any discomfort arises, pause and consult a rehabilitation therapist or physician.

- Volume: Carefully and slowly increase total training volume as pain improves and the bone lesion stabilizes.

Throughout this process, monitor spinal stability and the patient’s subjective feelings closely. If there is a significant increase in pain, local numbness, or any neurological deficit, seek medical evaluation and adjust the rehabilitation plan promptly.

Disclaimer

This report is generated by an intelligent medical-assisted system based on the available information and is for reference only. It cannot replace in-person consultation or professional medical advice. If you have any doubts or if symptoms worsen, please visit a hospital or consult a medical professional promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Eosinophilic Granuloma and Sever's apophysitis