An unusual cause of bone lesions in paediatric age

Clinical History

A 14-year-old female patient was sent to our institution with a history of recurrent pain and swelling in the right knee.

Imaging Findings

Plain radiography of the right femur showed an osteolytic lesion in the distal femoral metadiaphysis, with aggressive features, such as a permeative pattern and lamellated periosteal reaction (Fig. 1).

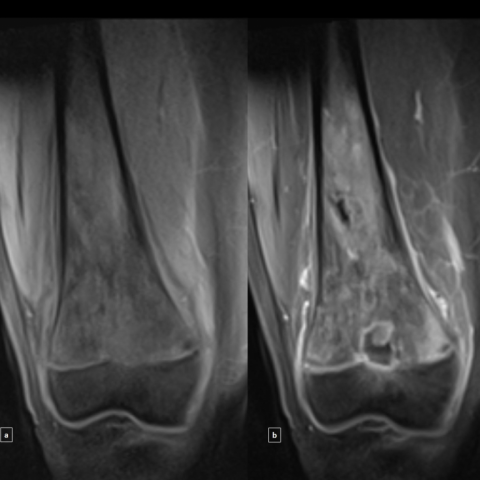

An MRI was performed in order to access the bone marrow and soft tissue extent of the lesion. It revealed multiple areas of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images within the distal femoral metadiaphysis, with physeal extension and interruption of the physeal scar. Cortical circumferential thickening, lamellated periosteal reaction and peri-tumoral oedema without evidence of soft-tissue mass was also present (Fig. 2 and 3). Sequences after contrast administration showed multiple areas of enhancement within the lesion (Fig. 4).

Surgical biopsy made the diagnosis of large B-cell lymphoma.

A bone scintigraphy was performed to exclude multifocal bone lesions. CT of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis excluded other sites of possible primary lesions and lymphadenopathies.

Discussion

Primary bone lymphoma (PBL) was initially defined as lymphoma occurring in an osseous site with no evidence of disease elsewhere for at least 6 months after diagnosis [1].

PBL is a rare condition that accounts for less than 5% of all primary bone tumours [2].

PBL can occur in all ages, with a peak prevalence among patients in the 6th to 7th decade of life. It is rare in the paediatric group, especially in patients younger than 10 years [2]. It occurs more often in male children (ratio 6:1) [3]. The femoral metadiaphysis is the most common site of involvement [2]. Others sites include pelvis, humerus skull, tibia and vertebras [4].

Clinically, PBL manifests with insidious and intermittent bone pain that can persist for months [5]. Other symptoms include local swelling and a palpable mass.

The radiographic appearance is not specific and varies from near normal appearing bone, to a wide spectrum of findings. The most common appearance is a lytic-destructive pattern (more than 70%), permeative or moth-eaten, and occasionally, with focal lytic areas with well-defined margins. Others findings: periosteal reaction (see in 60%), lamellated, layered or broken, cortical destruction, pathologic fractures, sequestra and soft tissues masses [2]. A mixed lytic/sclerotic pattern has also been described in lymphoma, particularly in Hodgkin disease [4].

MRI is useful to assess the extent of bone marrow, soft tissue involvement and in the follow-up after therapy. Sometimes, when symptomatic patients present with a “near normal” type of pattern on radiography, MRI is essential for further assessment as a more sensitive imaging modality [4]. Therefore, in the MRI we can see areas of bone marrow replacement (areas of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images) that enhance after contrast material administration. PBL may present a wide variability of intensities of T2-weighted images, but these areas are usually bright. Areas of hypointensity on T2 seem to be related to intralesional fibrosis [6]. Soft-tissue involvement is frequent.

In summary, although this is an uncommon cause of bone lesions and even rarer in the paediatric population, it should be on the differential when the clinical scenario of a solitary, permeative, metadiaphyseal lesion is present, particularly when a soft-tissue mass and marrow changes are associated with surprisingly little cortical destruction. The differences in treatment and the better prognosis compared with other primary malignant bone tumours emphasizes the need of an accurate and early diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Primary bone lymphoma - diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the right femur

MR Imaging. Axial (a) and coronal (b) T1-weighted images

MR Imaging. Sagittal T2-W; FS T2-W (axial; sagittal)

MR Imaging. Coronal FS T1-W

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

1. From the observed X-ray images (right knee joint, anteroposterior and lateral views), there is diffuse or “moth-eaten” destruction of the distal femur bone (near the knee joint). The local cortical margin remains relatively intact but slightly thinned, and a layered or “laminated” periosteal reaction can be seen.

2. On the MRI images, the lesion mainly involves the metaphyseal-epiphyseal region of the distal femur. T1-weighted sequences show low signal, while T2-weighted sequences mostly show relatively high signal intensity. Different degrees of bone marrow involvement and soft tissue swelling can be observed. After contrast enhancement, a significantly enhanced area is seen, indicating a high blood supply and involvement of the surrounding soft tissue.

3. Overall, even though cortical destruction is not very pronounced, local bone marrow signals are disordered, and there is a soft tissue mass, suggesting a malignant tumor.

II. Potential Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age, clinical manifestations (recurrent right knee pain and swelling), and imaging features, the following diagnoses or differential diagnoses are primarily considered:

-

Primary Bone Lymphoma (PBL):

Lesions often appear as a lytic “moth-eaten” bone destruction with mild cortical disruption but generally preserved cortical integrity, commonly accompanied by a soft tissue mass. Patients may have a prolonged history of pain and slow disease progression. Although this condition is rare in adolescents, it must be considered. -

Ewing’s Sarcoma:

Commonly affects children and adolescents, often involving the metaphysis or diaphysis with a typical layered (“onion skin”) periosteal reaction. Usually, it grows rapidly, showing more aggressive local features, and patients may present with systemic symptoms. -

Osteosarcoma:

Frequently observed in adolescents, typically presenting with osteogenic or mixed types of destruction and tumor bone formation. It is often associated with pronounced bone destruction and a soft tissue mass. Although there is no clear evidence of tumor bone formation in this case, osteosarcoma remains a differential diagnosis.

III. Final Diagnosis

Combining the patient’s age (14-year-old female), recurrent knee pain and swelling history, and imaging findings (moth-eaten bone destruction, mild periosteal reaction, significant bone marrow and soft tissue involvement but relatively minimal cortical destruction), together with possible upcoming pathology and immunohistochemical results, strongly suggests “Primary Bone Lymphoma (PBL)” as the most likely diagnosis. If uncertainty persists, a further biopsy (needle or surgical) is required to confirm the pathological diagnosis.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Strategies:

• Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy as Primary Approaches: For primary bone lymphoma, the standard approach includes chemotherapy (e.g., CHOP or R-CHOP) combined with radiotherapy. The specific regimen should be tailored according to the patient’s performance status, tumor stage, and pathological subtype.

• Surgical Intervention: Although not the first-line treatment for primary bone lymphoma, surgery may be considered when there is a fracture or the need to reduce the local tumor burden.

• Supportive Care: Includes nutritional support, pain management, and internal fixation for pathological fractures if necessary.

2. Rehabilitation / Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP Principle):

Given that the patient is an adolescent and the lesion is located in the lower limb, rehabilitation and exercise prescription should start gradually with low-intensity lower limb functional training following chemotherapy and radiotherapy, aiming to facilitate bone and soft tissue recovery while reducing discomfort and avoiding secondary injury.

• Frequency: 2-3 sessions per week initially, increasing to 3-4 sessions per week subsequently, based on patient tolerance.

• Intensity: Begin with low to moderate intensity (e.g., walking on flat ground, simple strengthening exercises), avoiding high loads. Use heart rate and RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion) to manage intensity.

• Time: Begin with 15-20 minutes per session, gradually extending to more than 30 minutes. Consider segmenting the session to avoid excessive fatigue.

• Type: Emphasize low-impact or non-weight-bearing exercises such as recumbent or semi-recumbent cycling, swimming, joint range-of-motion work, combined with basic strength training. As bone quality and local stability improve, partial weight-bearing or light resistance exercises can be introduced.

• Progression: Increase exercise intensity under professional supervision as pain and swelling subside and bone and soft tissue recover, while continuing regular assessments of bone healing and tumor status.

• Special Considerations: If bone fragility or reduced cardiopulmonary function occurs following chemotherapy or radiotherapy, adjust exercise intensity and duration accordingly, and ensure appropriate nutrition and protective measures.

V. Disclaimer

This report is based solely on the provided imaging data and initial clinical information and should not replace a professional in-person consultation or comprehensive evaluation. A definitive diagnosis and treatment plan require integration of pathological findings, laboratory tests, and the patient’s overall clinical status. Please seek follow-up diagnosis and treatment under the guidance of qualified medical professionals.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Primary bone lymphoma - diffuse large B-cell lymphoma