Dorsal defect of the patella

Clinical History

A 14-year-old girl presented with a history of persistent right knee pain.

Imaging Findings

Knee radiographs revealed a round, well-circumscribed, lucent lesion with sclerotic borders located in the superolateral aspect of the right patella. A follow-up radiograph a few months later demonstrated no changes in the lesion.

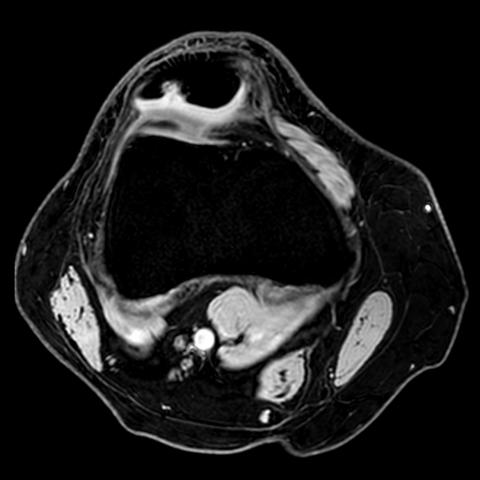

A computed tomography (CT) scan and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee were performed for further evaluation due to persistent pain. CT images of the lesion showed a rounded bony defect in the described location, surrounded by a sclerotic margin and abutting against articular surface of the patella. 3T MRI revealed the same findings, with intact overlying articular cartilage and no bone marrow oedema associated. No other injuries were identified.

The examination revealed a typical dorsal defect of the patella (DDP). The patient was managed conservatively.

Discussion

Background

DDP is an infrequent anomaly of ossification of the patella, consisting of a delay or failure in its developmental process [1–4]. It appears in less than 1% of the general population [2,4–6], and it is most common in adolescents [3,4]. It is rarely seen in adult patients and its disappearance has been documented, suggesting its spontaneous resolution [3,4,7]. It occurs bilaterally in up to one-third of cases [3,5,8,9]. DDP and bipartite or multipartite patella can associate, and they share the same typical location, leading to believe in a common origin [4,6,10]. The aetiology of DDP is not completely known; it has been postulated that increased stress caused by chronic trauma, combined with a deficient vascular supply can contribute to the disorder [3,4].

Clinical Perspective

In most cases DDP is asymptomatic. It is usually seen as an incidental finding observed on radiographs performed for other problems [2,3,5]. However, occasionally it may cause chronic knee pain in the absence of other abnormalities [2,3,7,8,10,11]. Some studies have shown that symptomatic cases with disrupted or invaginated articular cartilage into the defect may improve with surgical treatment [9,12]. Nevertheless, in more than half of the symptomatic cases managed with surgery or arthrography, there were no injuries in the articular surface [1,3].

Imaging Perspective

On plain radiographs the defect appears as a well-circumscribed, radiolucent lesion with a peripheral sclerotic margin invariably located on the superolateral aspect of the patella, abutting against articular surface [2–4,6–8]. This is a characteristic appearance which allows the diagnosis by itself, without biopsy or other intervention [4,11]. For this reason DDP was considered by Clyde A. Helms one of the skeletal “do not touch” lesions [7,13]. However, MRI is an excellent method in those cases with inconclusive plain radiograph findings for assessing the articular cartilage and for excluding coexisting disorders [2,6,8,11]. On MRI fluid-sensitive sequences DDP is seen as a hyperintense defect [2], with sclerotic margins. Lesions in the overlying articular cartilage and bone marrow oedema should not be present.

Outcome

The treatment consists of conservative management, with reduction of physical activity [1,7,11]. DDP tends toward spontaneous, slow healing [3,4]. Surgical treatment is rarely indicated, but in cases in which radiologic findings are not conclusive and the symptoms persist, curettage of the lesion by arthroscopy has resulted in relief of symptoms [4,8].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Dorsal defect of the patella

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

I. Radiological Findings

1. From the provided bilateral knee anteroposterior and lateral X-ray images, a relatively localized, near-circular radiolucent defect can be seen at the superolateral margin of the right patella, with a slightly sclerotic rim at the periphery. The lesion is located adjacent to the articular surface. The overall shape of the left patella is normal.

2. On CT axial and coronal images, there is a bony defect at the superolateral margin of the right patella, appearing as a low-density area with a clear boundary and partial sclerotic rim. The lesion diameter is small, and there is no obvious destruction of trabecular bone or cortical erosion.

3. On MRI T2-weighted and fat-suppression sequences, the defect presents as a hyperintense signal with a well-defined interface between the lesion and normal bone. There is no significant bone marrow edema around it, and no obvious abnormal signal changes suggesting damage to the patellar cartilage.

4. No noticeable soft tissue swelling or nearby joint effusion is observed. Other structures around the joint (ligaments, menisci, etc.) show no apparent abnormalities on the available images.

II. Possible Diagnoses

- Dorsal Defect of the Patella (DDP):

Based on the typical location (superolateral margin of the patella), its clear sclerotic border, and its common occurrence in adolescents, DDP is the primary consideration. It is a benign change caused by incomplete ossification, often presenting with no symptoms or only mild pain.

- Bipartite or Multipartite Patella:

Similar to delayed ossification, bipartite or multipartite patella can also present with segments or incomplete ossification in certain parts of the patella, typically exhibiting well-defined margins and possible fibrous or cartilaginous connections. X-ray or CT can help differentiate the separate bone fragment from the bony defect in this case.

- Focal Cartilage or Osteochondral Lesion:

A lesion such as an intra-cartilaginous pathology or osteochondroma can cause localized abnormalities. However, based on this case’s imaging presentation and lack of marked bony overgrowth or cartilaginous cap thickening, this diagnosis is less likely.

III. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age (14 years, during skeletal development), clinical presentation (persistent knee pain), and radiological findings (a round defect in the superolateral patella, clear sclerotic margins, with no cartilage or bone marrow damage), the most likely diagnosis is:

Dorsal Defect of the Patella (DDP).

Further confirmation may rely on follow-up imaging if symptoms persist and to observe response to conservative management. In clinically suspected but radiologically atypical cases, arthroscopic exploration may be considered to exclude other pathologies.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Strategy

- Conservative Treatment: Most patients with dorsal defects of the patella can be managed conservatively, including:

- Reducing strenuous activities to avoid excessive patellofemoral stress.

- Short-term use of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) if needed to alleviate pain.

- Regular follow-up with imaging. As pain resolves, normal physical activities may be resumed.

- Surgical Treatment: Only consider arthroscopic debridement or curettage if conservative measures fail and symptoms significantly impact daily life, or if imaging strongly suggests cartilage damage.

2. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP Principles)

- Frequency:

Perform low-impact knee exercises 3–4 times per week (e.g., swimming, cycling), adjusting frequency based on symptoms and pain severity.

- Intensity:

Start with low to moderate intensity. If discomfort or pain significantly increases, reduce intensity and rest as needed.

- Time:

Each session should last about 20–30 minutes, possibly divided into blocks of 10–15 minutes with rest intervals.

- Type:

Choose aerobic activities with minimal joint impact (e.g., stationary cycling, elliptical, swimming). Incorporate moderate strength training for the quadriceps and hamstrings but avoid deep squats or movements placing high stress on the patellofemoral joint.

- Progression:

Gradually increase exercise duration and intensity every 2–4 weeks as pain and function improve. If pain worsens at any point, revert to the previous step or reduce training volume.

- Volume and Pattern:

Adopt a “little but often” approach. Each workout should not be overly taxing; it may be spread over several short sessions. Patients with patellar dysplasia or fragile bone structures should progress cautiously and continuously monitor symptoms.

3. Precautions

- If acute knee swelling, inability to bear weight, or severe pain occurs, stop the related activities immediately and seek medical attention.

- During the recovery phase, any strength training should be performed under the supervision of a professional therapist or trainer, increasing intensity in a gradual manner.

- If other lower limb structural issues exist (e.g., flat feet, high-arched feet), a concurrent assessment of gait and posture is recommended. Use orthotics or other supportive devices if needed.

Disclaimer: This report provides a reference-only medical analysis based on the supplied materials and cannot replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. Specific treatment plans should be tailored to the patient’s condition and carried out under specialist guidance.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Dorsal defect of the patella