Bilateral long head of triceps exertional rhabdomyolysis induced by stretching

Clinical History

A 24-year-old man presented with sudden onset bilateral painless upper arm swelling after stretching both his arms behind his head while sitting on a chair. He regularly attends a gym and worked out the day before, focusing on his legs. He gave no history of recent increased arm exercise or trauma.

Imaging Findings

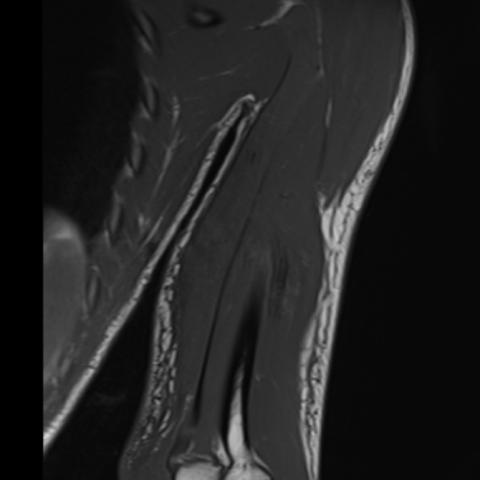

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his upper limbs showed bilateral symmetrical oedema localised to the long head of the triceps. There was no defect or fatty atrophy (Figures 1 and 2).

Prior to his MRI, initial concerns related to possible vascular occlusion led to a chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT) angiogram of his upper limbs (not shown), which were both normal.

As the cause of oedema was unclear, a nuclear medicine lymphoscintigram was performed, which demonstrated normal lymphatic drainage bilaterally (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Muscle oedema on MRI is a nonspecific finding seen in myositis and rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis is a well-described syndrome resulting from either direct myocyte injury or cell energy depletion leading to an imbalance of cell electrolytes. This leads to muscle fibre necrosis and release of breakdown products into the circulatory system, including myoglobin, electrolytes and creatine kinase (CK). It can cause potentially life-threatening consequences, including acute kidney injury and compartment syndrome [1].

Rhabdomyolysis can be caused by any entity leading to muscle injury, including exertion, trauma, alcohol, viral, autoimmune, medication, drug reactions or other rarer causes [2,3].

Diagnosis requires a combination of a significantly elevated CK >10,000 IU/L and relevant signs and symptoms, including non-pitting oedema, pain, nausea and dark brown urine or oliguria [4,5].

In our case, examination revealed extensive subcutaneous oedema in both upper limbs with no skin rashes or neurological deficit. Serum CK was markedly elevated (>14000 IU [normal range <300 IU]). The patient was systemically well with no other biochemical abnormality detected, and lymphatic drainage was normal on imaging. Urinalysis was normal. Given that he was extremely fit and active, a history of exercise revealed that he had not exceeded his normal limits recently.

Symmetrical rhabdomyolysis in a limited distribution is unusual and should usually raise the suspicion of atypical myositis, which includes inflammatory and autoimmune causes such as polymyositis, eosinophilic myositis, overlap myositis or dermatomyositis [1]. In this patient’s case, an extended myositis antibody screen and eosinophil count were normal. In conjunction with an absence of muscle weakness and other co-morbidities (such as connective tissue disease), the likelihood of an inflammatory myositis, such as overlap myositis, was reduced. The absence of skin changes excluded dermatomyositis.

Other common rhabdomyolysis precipitants, including recent trauma, alcohol, illicit drugs, medication and infection, were excluded. There was no relevant family history to suggest a genetic predisposition to congenital myopathies.

The patient was managed with intravenous fluids and rest. He recovered rapidly, with his CK reducing to <3500 IU 48 hours post-admission and normalised to 194 IU on follow-up 2 weeks later. Marked improvement with conservative management further reduced the likelihood of an underlying inflammatory myositis, which is frequently managed with glucocorticosteroids. Given the rapid improvement, a biopsy was deemed unnecessary. He declined follow up MRI to confirm the resolution of imaging abnormalities.

Overexertion remains one of the most common causes of muscle injury, typically in the setting of significant relative exercise or trivial exertion in significant circumstances. Additional factors can play a role, including poor hydration and increased environmental temperature. Repetitive eccentric muscle activity is also known to carry a higher risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis through excess tension causing structural cell damage [6]. It is possible that significant overextension of muscle fibres through stretching, in this case, led to muscle fibre injury triggering rapid rhabdomyolysis.

Localised exertional myositis is rare but has been demonstrated on several occasions in the context of significant strenuous overactivity relative to the individual’s baseline performance [7,8]. Unilateral occurrences in the long head of the triceps after considerable exertion are also described but are rarer still [9,10]. Bilateral rhabdomyolysis of the long head of the triceps is extremely rare. It has only been described once after intense exercise [11] and never from such minor exertion.

This case highlights the possibility of localised exertional rhabdomyolysis following trivial activity in a healthy adult without underlying pathology or evidence of other common triggers. Once other differentials are excluded, prompt rehydration and renal monitoring are required to reduce potential morbidity and mortality [1].

Written informed patient consent for publication has been obtained.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Bilateral long head of triceps exertional rhabdomyolysis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

MRI left upper limb

MRI right upper limb

Normal lymphoscintigram of both upper limbs

Imaging Findings

Based on the provided bilateral upper limb MRI images, the following can be observed:

- On T2-weighted and corresponding water-sensitive sequences, there is a marked increase in signal intensity in the long head of the triceps brachii and surrounding soft tissues on both sides, suggesting muscle edema.

- No clear soft tissue mass lesion or evidence of bone involvement is noted.

- The local muscle boundaries remain intact, with no apparent tendon rupture or fracture.

- Combined with the lymphangiography examination (as shown in the figure), no significant lymphatic drainage obstruction is observed.

Summarizing these imaging findings, the primary emphasis is on diffuse edema of the muscles in both upper arms, indicating an acute or subacute muscle injury process.

Possible Diagnoses

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation (sudden bilateral swelling of the upper arms, minimal pain, a history of regular exercise but no recent excessive weight training) and the imaging findings, the possible diagnoses include:

- Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

- Muscle damage occurs with acute overstretching or extremely intense training, and MRI shows significant T2 hyperintensity.

- It is often accompanied by a marked rise in CK (over 14,000 IU in this case), which is a key indicator of this condition.

- Inflammatory Myopathy (e.g., polymyositis, dermatomyositis)

- Clinically, this often presents as symmetrical muscle weakness with elevated CK, and imaging can show muscle edema.

- In this case, there are no typical skin changes, no obvious muscle weakness, and normal relevant antibodies and peripheral eosinophil counts, making this diagnosis less likely.

- Infectious or Drug-Related Myositis

- Usually accompanied by fever, local pain, or systemic symptoms; or a history of drug use.

- In this case, there is no clear sign of infection, nor is there any relevant history of medication or toxin exposure.

Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s youth, strong physique, extremely elevated CK (>14000 IU/L), bilateral arm muscle edema, and the absence of other obvious triggers, the most likely diagnosis is:

Bilateral Localized Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

This diagnosis is also consistent with MRI findings (abnormal T2 hyperintensity in the local muscle area), and the rapid improvement of CK levels and clinical symptoms after short-term conservative treatment further supports this conclusion.

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Treatment Strategy

- Acute Phase Management: Primarily supportive treatment, including intravenous fluids, maintaining electrolyte balance, and monitoring renal function to prevent acute kidney injury.

- Medications:

- Generally, corticosteroids are not required; if there is no concurrent inflammatory myopathy, they may be omitted.

- Depending on the severity, analgesics or muscle relaxants may be considered to alleviate discomfort.

- Follow-Up Observation: Once CK decreases to near-normal levels and there is no worsening of muscle pain or swelling, rehabilitation or normal activities may be considered.

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription

After symptom relief and passage through the acute phase, a gradual return to daily activities and training is recommended. The following FITT-VP principles may be referenced:

- Frequency: 2-3 times per week of low-intensity lower limb and core muscle training, progressively resuming upper limb exercises.

- Intensity: Start with bodyweight exercises or very light resistance, ensuring no significant pain before gradually increasing the load.

- Time: Begin with 20-30 minutes per session, and as physical capacity and symptoms improve, gradually extend to 30-45 minutes.

- Type: Low-impact aerobic exercises (e.g., swimming, elliptical) are recommended first, followed by a small amount of upper limb strength training, avoiding excessive stretching or eccentric contractions.

- Volume: Adjust according to individual recovery speed, ensuring proper form and safety before gradually increasing volume for both small and large muscle groups.

- Progression: Every 2-4 weeks, consider increasing resistance or exercise duration by 10-20%. If significant soreness or edema occurs, promptly adjust the plan.

Since this case involved acute muscle injury, special attention should be paid to hydration and monitoring fatigue levels to prevent recurrence or further excessive stretching.

Disclaimer: This report is based solely on the provided patient history and imaging information for reference purposes and cannot replace in-person medical consultation or professional medical advice. If you have any questions or changes in your condition, please seek medical attention and specialist guidance promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Bilateral long head of triceps exertional rhabdomyolysis