Thoracic venous obstruction and vanishing bone metastases

Clinical History

The patient was a 46-year-old female with a past medical history relevant for short bowel syndrome, requiring long term parenteral nutrition and multiple PICC line insertions.

After presenting with severe abdominal pain and vomiting, she underwent an enhanced CT scan of the abdomen to rule out bowel obstruction.

Imaging Findings

The post-contrast CT demonstrated an apparent sclerotic lesion within the vertebral body of T11, with serpiginous borders and extending into the pedicles but not disrupting the bone cortex.

A whole spine MRI was performed and no lesion was identified. The appearance of the T11 vertebral body was considered due to selective contrast opacification of the vertebral plexus due to reflux of contrast from the azygos and hemiazygos veins, which appeared enlarged.

A careful scrutiny of the paraspinal soft tissues on CT revealed the presence of significantly dilated vessels, representing an enlarged para-vertebral plexus.

The patient was known to have obstruction of the left brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava, as demonstrated on previous MRI and angiography imaging, which predisposed her to an increased risk of developing vertebral collateral vessels.

Discussion

Vanishing bone metastases are a recognised entity identified on post-contrast CT of patients with thoracic venous obstruction, due to alternative venous drainage pathways and engorgement of the paravertebral venous system [1].

The paravertebral venous plexus normally surrounds the vertebrae, has no valves and can be subdivided into four portions: epidural vertebral venous plexus (consisting of an anterior and a posterior plexus), external vertebral venous plexus, basivertebral veins and intervertebral veins. There are extensive anastomoses with the renal veins, inferior vena cava, brachiocephalic, azygos and hemiazygos veins [2].

There are five recognised patterns of collateral venous pathways leading to vertebral body pseudo-enhancement:

- Anterior and lateral thoracic and superficial thoracoabdominal collaterals

- Mediastinal collaterals, including oesophageal, tracheobronchial and diaphragmatic veins

- Azygos, hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos collateral

- Vertebral and paravertebral collaterals, including anterior and posterior paravertebral plexuses, anterior and posterior epidural plexuses, intervertebral and basivertebral veins

- Unusual collaterals including porto-caval and cavo-pulmonary pathways [2].

It is not possible to accurately predict the pattern of venous collateral drainage on the basis of the level and characteristic of obstruction but involvement of the upper thoracic vertebrae is most commonly observed in case of superior vena cava obstruction above the azygos vein arch, whereas involvement of the lower thoracic vertebrae is more common in case of obstruction below the azygos arch [2].

The prevalence of this phenomenon has been described as high as 47% in patients with venous obstruction vs 5% in patients without obstruction [3].

The erroneous interpretation of these finding as a vertebral metastasis can lead to unnecessary investigations and procedures for patients, such as biopsy, leading to increased radiation dose and morbidity.

A careful review of the paravertebral tissues can help identify an enlarged venous plexus, which in combination with intravertebral contrast enhancement, should raise the possibility of this phenomenon occurring.

This is therefore an important entity to recognise for the general radiologist and MSK radiology subspecialist alike.

We would like to stress the importance of a few learning points, identified while reviewing the case:

- Be aware of selective vertebral body venous enhancement in patients with obstruction of the SVC;

- Scrutinise previous studies, particularly unenhanced CTs, if an unexpected high-density area is seen within the vertebrae on an enhanced CT study;

- If in doubt, MRI or unenhanced CT will help identifying the correct diagnosis.

Written informed patient consent for publication has been obtained.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Pseudo-pathologic vertebral body contrast enhancement due to thoracic venous obstruction

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Post contrast CT, bone window

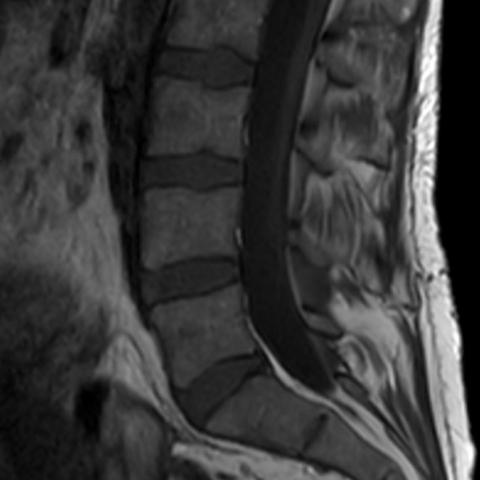

Thoraco-lumbar spine MRI

MR venogram reformat

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

1. From the provided enhanced CT images of the chest and abdomen, a relatively increased density shadow is seen in certain thoracic vertebral bodies, with the overall morphology and bone structure largely preserved. The paravertebral venous plexus around these vertebrae appears slightly widened.

2. Lumbar MRI (T1 and T2 weighted images) shows no significant abnormal bone marrow signal inside the vertebral bodies, and no clear features indicative of neoplastic infiltration. The shape and signal of the spinal cord are basically normal, and no intraspinal mass is observed.

3. On the chest vascular reconstruction images, there is evidence of abnormal, possibly tortuous or dilated collateral venous networks near the subclavian vein or superior vena cava, suggesting potential venous outflow obstruction.

II. Potential Diagnosis

- Metastatic Vertebral Lesion: Due to the appearance of an abnormally high-density area on enhanced scans, if the patient has a history of malignancy, it could easily be misdiagnosed as bone metastasis. However, the MRI findings do not support substantial tumor infiltration, and clinical caution is advised to rule this out.

- Vertebral Vascular Lesion or Paravertebral Venous Plexus Distention: Obstruction of the superior vena cava or subclavian vein may lead to engorgement and tortuosity of the paravertebral and intravertebral venous plexuses, resulting in pseudo-enhancement that can mimic a “bone lesion.”

- Other Bone Density Abnormalities (e.g., Hemangioma): Common manifestations include high signal intensity on T1-weighted images or high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, which differ from the imaging findings in this case.

III. Most Likely Final Diagnosis

Taking into account the patient’s history (short bowel syndrome, prolonged PICC placement) and the imaging findings (apparent enhancement of thoracic vertebral bodies but no MRI evidence of neoplasm infiltration, prominent collateral venous networks), the most likely diagnosis is:

Paravertebral venous plexus dilation due to impaired outflow in the superior vena cava (or subclavian vein), leading to “pseudo-enhancement” of the vertebrae (“disappearing bone metastasis” phenomenon).

This imaging appearance does not represent true metastatic bone disease or any other space-occupying lesion, so biopsy is not required. If necessary, further dynamic imaging follow-up or non-enhanced CT/MRI may be performed for confirmation.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Strategy:

- The main point is to identify and address the cause of venous outflow obstruction. If there is stenosis or occlusion of the superior vena cava, consider interventional angioplasty, stenting, or surgical intervention.

- Symptomatic treatment: In the presence of significant venous hypertension complications (such as edema of the head, neck, or upper limbs), diuretics or local decompression measures may be used as appropriate.

- Continued monitoring: If the patient is asymptomatic and imaging confirms pseudo-enhancement, clinical and imaging follow-up may suffice, avoiding unnecessary radiation exposure or invasive procedures.

2. Rehabilitation/Exercise Prescription Recommendations:

- Gradual Progression: Given the patient’s short bowel syndrome, nutritional support is essential. Work with the nutrition and rehabilitation teams to gradually restore physical strength.

- Type of Exercise: Low-impact aerobic exercises are recommended, such as slow walking on flat ground or using a stationary bike. Avoid intense activities that impose excessive load.

- Frequency: Start with three sessions per week at moderate intensity (e.g., slight increase in breathing rate but still able to talk), each lasting about 20 minutes. Increase to four to five sessions per week for 30 minutes each as tolerated.

- Intensity: Follow an individualized approach. Exercise should not cause evident fatigue or excessively high heart rate. Heart rate monitoring or subjective fatigue rating can be used if necessary.

- Progression: Once the patient’s cardiopulmonary and skeletal conditions are stable, gradually extend exercise time to 40–45 minutes or slightly increase the exercise intensity within a tolerable range.

- Precautions: If the patient has osteoporosis or malnutrition, extra care is required to protect bones and cardiopulmonary function, and to prevent falls or fractures. Discontinue exercise and seek medical advice if symptoms such as chest tightness or dizziness occur during activity.

V. Disclaimer

This report provides a reference analysis based solely on the supplied images and limited clinical information. It does not replace a face-to-face consultation or professional medical guidance. If any acute clinical symptoms arise or if you have any concerns, please seek evaluation and treatment from a qualified healthcare facility promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Pseudo-pathologic vertebral body contrast enhancement due to thoracic venous obstruction