Suprascapular neuropathy due to a spinoglenoid notch ganglion mimicking a rotator cuff tear

Clinical History

A 5-month history of left shoulder pain. There was no obvious precipitating factor and the only abnormality on physical examination was an element of painful arc.

Imaging Findings

The patient presented with a 5-month history of significant pain and weakness in the left shoulder with no obvious precipitating event. On examination there was no muscle wasting, an element of painful arc with weakness of supra and infraspinatus and normal power in the subscapularis muscle.

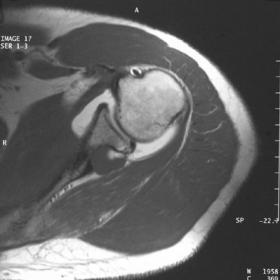

No abnormality was seen on plain radiography. Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) demonstrated a well-defined 1.5cm x 2cm ovoid lesion located in the spinoglenoid notch, projecting towards the suprascapular notch. It exhibited three signal characteristics: (1) an area with low signal on T1-weighted images, and high signal on T2-weighted images, in keeping with fluid; (2) high signal on T1-weighted, STIR and fat saturated images after contrast medium injection, implying a communication with the joint, and (3) an area, located anteriorly, showing low signal on T1- and T2-weighted images, probably indicating a gas collection (Figs 1,2).

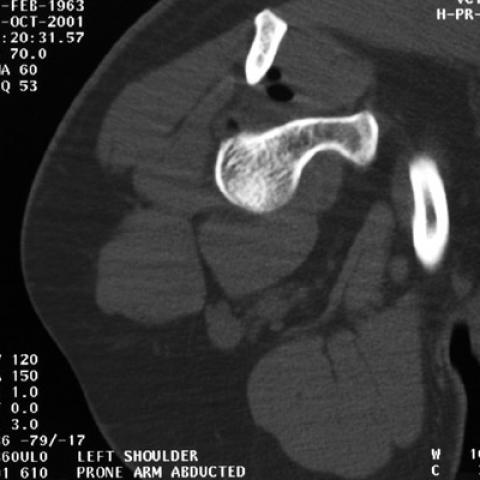

There was also a tear of the posterior glenoid labrum outlined by contrast medium and a small SLAP lesion. The rotator cuff was intact. On a subsequent CT examination the area of low signal was seen to move between the supine and prone positions, confirming a gas collection (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The suprascapular nerve arises from the brachial plexus (roots C4, C5 and C6) and passes through the scapular notch beneath the transverse scapular ligament, dividing into a branch which supplies the supraspinatus muscle and one that passes through the spinoglenoid notch to supply the infraspinatus muscle. Depending on location trauma, anomalies of the notch, a hypertrophic transverse scapular ligament, a ganglion cyst or other SOL can result in a neuropathy affecting either only the infraspinatus or both the infra and supraspinatus muscles [1]. Sporting activities involving overhead motion such as tennis, swimming, weight lifting and volleyball can lead to traction injuries [2,3].

There are several theories regarding the pathogenesis of ganglion cysts, including myxoid degeneration of the joint capsule, joint fluid leaking through a weak capsular area and tears in the labrum (hip and shoulder). Shoulder ganglion cysts have been associated with gleno-humeral intra-articular pathology, namely a posterior capsulolabral tear [4] (as seen in this patient). The presence of gas and contrast medium within the ganglion in this case supports a theory of communication between the joint and ganglion cyst.

Gas-containing ganglia have rarely been reported [5]; to our knowledge this is the first concerning a shoulder ganglion. Gas may be seen radiographically in a number of situations. Its presence is normal in the vacuum phenomenon when a joint is subjected to traction by distracting apposing joint surfaces. Intra-articular gas is also present in established degenerative conditions of the spine and peripheral articulations. Serial CT studies may show the cyst filling alternately with gas and fluid.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Communicating spinoglenoid ganglion

Liscense

Figures

T1-weighted spin echo (a,b) and fat saturated (c,d) axial MR arthrogram images

Coronal MRI images

Axial CT images

Radiological Findings

1. On MRI sequences, a cystic lesion is visible in the posterior aspect of the shoulder joint, located near the posterior joint capsule of the glenoid. The lesion exhibits mixed high and low signal intensities, and a gas signal can be observed inside, suggesting a possible communication with the joint cavity.

2. The lesion is adjacent to the attachment sites of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. There is noticeable abnormality in the contour of the joint capsule and the labrum region, indicating a possible posterior labral tear.

3. CT images also show a cyst-like shadow behind the glenoid with low internal density and visible gas density. No apparent narrowing of the joint space is observed, but there is evidence of communication between the cyst and the articular surface.

4. Overall, the bony structures are intact, with no overt signs of fracture. No direct evidence of a large-scale rotator cuff tendon tear is identified (though the posterior lesion may be suspicious for causing compression of the infraspinatus muscle belly or tendon). Clinical examination is needed for further differentiation.

Possible Diagnoses

Based on the above imaging findings and clinical history, the following are potential diagnoses or differential diagnoses:

1. A cyst in the spinoglenoid notch or suprascapular notch causing nerve entrapment: A cyst containing gas, combined with the patient’s shoulder pain and possible painful arc, points to the involvement of the infraspinatus or supraspinatus nerve branches.

2. A glenoid labral tear with intra-articular fluid or gas leakage: Imaging findings of a cyst connected to the posterior labral tear with gas intrusion suggest a communication between the joint cavity and the cyst.

3. A simple synovial or mucous cyst near the joint capsule: Although it can present with similar imaging findings, the presence of prominent gas components and labral changes strongly supports a pathology communicating with the joint cavity.

Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age, the five-month history of left shoulder pain, and imaging evidence of a posterior labral tear with gas entering the cyst, the most likely diagnosis is:

“Posterior shoulder labral tear with a gas-containing articular cyst (posterior glenoid cyst), leading to potential infraspinatus nerve compression.”

If additional confirmation of the pathology or the extent of the labral tear is required, arthroscopic evaluation or further imaging with contrast can be considered.

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Conservative Treatment:

This may include pain medication, local injection (e.g., corticosteroids), and physiotherapy (e.g., ultrasound, electrical stimulation). It is suitable when symptoms are not severe and tendon function is relatively preserved. If the cyst is small and pain is tolerable, conservative management with regular follow-up is typically considered first.

2. Arthroscopic Surgery:

If conservative treatment proves ineffective, or imaging confirms significant compression of the suprascapular or infraspinatus nerve by the cyst, along with a concurrent labral tear, surgical intervention should be contemplated. Arthroscopic excision of the cyst and repair of the labral tear can alleviate nerve compression and prevent further deterioration.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP Principle):

• Frequency (F): During the initial stage, perform exercises targeting shoulder flexibility and muscle strength 3–4 times per week.

• Intensity (I): Begin with low-intensity isometric exercises, then gradually transition to moderate-intensity resistance training (such as using resistance bands) while progressively increasing the load.

• Time (T): Each session should last about 20–30 minutes, split into sets. Schedule rest days between sessions to allow recovery.

• Type (T): Start with gentle range-of-motion exercises (e.g., forward flexion, abduction, internal and external rotation). As pain decreases, introduce more advanced strength training (isometric, isotonic), but avoid sudden or excessive stretching or rotation.

• Progression (P): As pain subsides and strength improves, increase the resistance band’s tension, add light weights, and gradually return to daily activities or sports that require shoulder function.

• Volume and Plan (VP): Increase the number of repetitions and sets according to tolerance and supportive muscle strength. Reassess shoulder stability dynamically and adjust the program accordingly.

Throughout rehabilitation, it is crucial to monitor the patient’s pain and the stability of the shoulder joint to avoid exacerbating inflammation or tears. If there is bone fragility or other systemic comorbidities, adjustment of exercise intensity and technique is necessary to maintain safety.

Disclaimer:

This report offers a reference-based analysis derived from current imaging and clinical information and does not replace a face-to-face specialist diagnosis or treatment. Patients should promptly seek professional medical advice if there is any change in condition or the appearance of new symptoms, following the guidance of qualified healthcare professionals.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Communicating spinoglenoid ganglion