骨外间叶性软骨肉瘤

临床病史

一名40岁的男性,右大腿可触及肿块,过去五个月其大小逐渐增大。

影像学表现

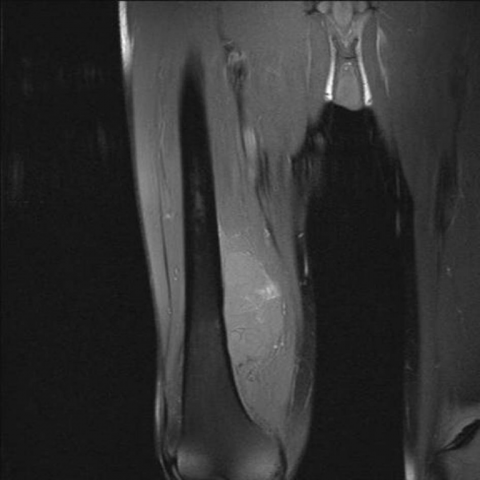

40岁男性因右大腿前内侧可触及、无痛性肿块被转诊至我院,周围无皮肤发红反应。行多普勒超声检查示卵圆形病灶,内部回声结构不均匀并伴有血流增多。 磁共振成像(MRI)显示,在右大腿的前、内和后肌室出现软组织肿块,浸润到股肌(中间头及内侧头)、内收小肌、股二头肌、半膜肌和半腱肌。股骨远端干骺端后内侧的皮质骨可见受侵,并累及髓腔。浅股动脉和股静脉以及坐骨神经被肿瘤包围。T2加权像(图1)显示肿块信号强度增高,脂肪抑制T1加权像中可见高信号区域,与出血灶一致(图2)。钆增强影像上,肿块呈不均匀强化(图3)。这些发现提示为侵袭性软组织肿块。 组织学分析显示在明确的软骨区域旁,有间质的新生性增殖区,由成团的小细胞组成,细胞核呈椭圆形、高度染色,并聚集在一起,同时可见血管裂隙与坏死区域(图4)。

病情讨论

骨外间叶性软骨肉瘤(Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, EMC)最早由Lichtenstein和Bernstein于1959年报道为一个独立的病种,描述为一种罕见的、具有明显远处转移倾向的侵袭性软骨肉瘤亚型。该肿瘤通常起源于骨,但约30%的病例发生在骨外部位(1),如中枢神经系统、软组织和纵隔(2)。EMC具有双峰年龄分布:头颈部肿瘤主要发生在生命的第3rd个十年,而大腿部肿瘤则最常见于生命的第5th个十年(3, 4)。临床症状并不特异,最常见的表现是一个缓慢增大的无痛性软组织肿块(5)。这种病变病程侵袭性强,常发生转移,通常转移至肺和淋巴结(2, 4, 5)。 EMC主要由大片未分化的间叶组织细胞构成,分化的软骨成分通常只占病灶的一小部分(2, 3)。对疑似EMC的成像评估首先采用常规X线检查,可显示钙化,从而提示疾病诊断,同时也能发现骨的受累(6)。有些报告指出,50%-100%的EMC在常规放射或CT检查中可显示弧形、环状、点状以及高度致密的钙化(3, 4)。MRI是评估EMC的首选影像学方法,可显示肿瘤的构造及肿块范围(3, 6)。尽管MRI在识别、描绘和分期EMC方面具有优势,但在准确定性方面仍存在局限;大多数病灶在T2加权像上呈高信号,在T1加权像上呈与肌肉等信号,静脉注射钆剂增强后表现为明显的异质性强化(6),这与本例患者所见相一致。 同样,部分文献描述的EMC影像学特征与肿瘤内矿化的形式和范围有关,这些矿化可形成两个清晰分界的区域。钙化区在T1及T2加权成像上均呈低信号,而非钙化区在T1加权像上表现为与肌肉等信号,T2加权像上为中等信号。与其他类型的软骨肉瘤相比,EMC在T2加权像上通常表现为更低的信号强度,这与其更高的细胞密度及更低的含水量有关(2,5)。增强后EMC会出现显著且不均质的强化,这同样与其高度细胞性相关。虽然在某些情况下,我们可以从影像学外观上诊断EMC,但最终诊断仍需结合组织学结果以制定恰当的治疗方案。成像不仅能提供分期的重要信息,还可帮助定位肿瘤活检部位,从而获取具有代表性的标本。

鉴别诊断列表

最终诊断

骨外间叶性软骨肉瘤

证书

(无可翻译的英文内容)

图像分析

轴向T2加权图像

冠状位脂肪抑制T1加权图像

注射钆造影剂后冠状位脂肪抑制T1加权图像

软组织肿块的组织学样本

影像学发现

患者右大腿 MRI 显示软组织内可见一明显肿物影,呈不规则形态。肿瘤信号特点:

- T1 加权像:病变表现为与肌肉信号大致等信号,局部可见稍低或混杂信号区域。

- T2 加权像:病变整体呈高信号,但其内可见信号较低的成分,提示可能存在钙化或纤维成分。

- 增强扫描:肿物呈明显不均匀强化,暗示肿瘤血供丰富及内部组织成分复杂。

从 MRI 影像可见病变累及大腿内软组织,边界部分清晰,部分与周围组织分界欠清。尚未见明确的骨质破坏,但需仔细排除潜在骨皮质侵蚀或骨内转移。局部血管神经通道并无明显受压变形征象,需与周围肌群受累程度相结合判断。

潜在诊断

-

软骨肉瘤(尤其是骨外软骨肉瘤/间质性软骨肉瘤):

文献报道此类肿瘤可表现为软骨信号特征(T2 高信号),常存在钙化或软骨基质信号,且有明显强化。患者年龄(40 岁)和近 5 个月快速增大亦符合此可能。

-

脂肪肉瘤或其他高等级软组织肉瘤:

有些高等级肉瘤也可出现软骨或类似软骨的成分,T2 高信号明显、形态不规则,且可能有混杂信号。增大速度快时需鉴别。

-

纤维肉瘤或未分化多形性肉瘤:

虽然 T2 信号往往较高,但也可出现低信号成分。需结合组织学和病理学进行区分。

最终诊断

结合患者年龄、临床表现(逐渐增大的软组织肿物)、并在 MRI 上显示明显软骨基质或钙化成分,且病理组织学支持“间叶性软骨肉瘤(Extraskeletal Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma, EMC)”的结论,最符合诊断为 骨外/间叶性软骨肉瘤。

如果仅凭影像无法完全排除其他软组织肉瘤,仍需结合病理组织学和免疫组化进行确认。如已获得病理证实,则诊断更明确。

治疗方案与康复计划

治疗策略

- 手术治疗:根治性切除是主要治疗手段,需争取获得完整的肿瘤切除边界。根据术中及术后病理,或需结合化疗和(或)放疗。

- 辅助治疗:间叶性软骨肉瘤恶性程度高,病理确诊后通常需结合综合治疗,包括化疗和放疗,以减少复发和远处转移的风险。

康复/运动处方

康复训练需遵循循序渐进和个体化原则,具体可参考以下示例:

- 术后早期(组织修复期):

- 以保护患肢、预防血栓及循环障碍为主要目标。可做踝泵运动、直腿抬高(如未影响手术切口)等低强度练习。

- 频率:每日 2-3 次;时间:每次 10-15 分钟,动作缓慢。

- 中期(力量及关节活动度恢复期):

- 在医生或康复治疗师指导下进行下肢力量、关节活动度及核心肌群训练,如屈伸膝关节、坐姿或仰卧位的髋关节活动。

- 频率:每周 3-4 次;强度:心率维持在最大心率的 50-60%;持续 30 分钟左右。

- 后期(机能重建及Return to Daily Life):

- 可逐渐增加运动强度,结合姿势及步态训练、简单抗阻训练(如轻重量负荷的抗阻练习)、低冲击有氧运动(如室内固定自行车、游泳等)。

- 频率:每周 3-5 次;强度可提升到最大心率的 60-70%;时间:30-45 分钟。

在整个康复过程中,应监测患肢疼痛、肿胀情况及全身反应,如出现异常症状,应及时就诊或调整康复方案。

注意事项:由于肿瘤手术及综合治疗对机体有一定损伤,患者骨质可能会较脆弱,心肺储备功能可能下降,故运动强度调整时需谨慎,防止跌倒和再损伤。

免责声明

本报告为基于现有临床及影像资料所做的参考性分析,不能替代线下面诊或专业医生(尤其是骨科、肿瘤科)面对面的诊断与治疗方案制定。如有疑问或症状加重,请及时前往医院或者寻求专科医生的进一步评估与处理。

人类医生最终诊断

骨外间叶性软骨肉瘤