Bilateral Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fractures

Clinical History

We present a 15-year-old Caucasian male who sustained a hyperflexion injury to his left knee playing football. Six months later he injured the right knee in a similar way. This series of radiographs

illustrates bilateral avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle and the treatment of these injuries.

Imaging Findings

The patient is a fit and well 15-year-old school boy with no previous history of bone injury or pathology. His first presentation was with a painful, swollen left knee and inability to weight bear

following an injury sustained during a game of football. A hyperflexion type injury was described. On examination the knee was swollen and a reduction in movement secondary to pain was noted.

Radiographs were taken and revealed a type III avulsion fracture of the left tibial tubercle. The initial management was analgesia, long leg backslab and elevation. The following day he had surgical

fixation of the fracture by open reduction and fixation with a 55mm partially threaded cancellous screw. Six months later he represented following another injury during a game of football. On this

occasion he was hit by another player in the back of the right leg causing hyperflexion. He described a 'pop' sounds and inability to weight bear. The knee was swollen and painful with a reduced

range of motion. Radiographs again illustrated a type III fracture of the right tibial tubercle. The treatment instituted was identical to that six months earlier except for a change in surgeon. On

each occasion the patient was placed in a long leg cast for six weeks and gradually permitted to increase weight bearing status. After six weeks the cast was removed and he was referred to

physiotherapy. He is currently doing well and has no complications from either knee.

Discussion

Acute bilateral avulsion injury of the tibial tubercle is rare and should not be confused with Osgood Schlatter disease. It occurs either sequentially or simultaneously. The majority of acute traumatic avulsions of the tibial tubercle occur in males. The avulsion occurs when the patella tendon exceeds the combined strength of the physis underlying the tubercle and the surrounding periosteum and perichondrium. The injury can occur through either violent contraction of the quadriceps muscle against a fixed tibia eg when jumping, or acute passive flexion of the knee against a

contracted quadriceps.

There are five types of tibial tubercle fracture, types 1-3 were initially described by Watson Jones then revised by Ogden to 5 types. Types 1-3 usually occur in the younger adolescents, types 4 – 5 occurring in the 15 to 17 year age group. Type 1 is distal to the ossification centres, the fragment may be displaced anteriorly and proximally. Type 2 the fracture extends proximall to the tibial eiphysis, the fragmant may be comminuted. Type 3 the fracture extends into the knee joint displacing the fragmant anteriorly, the fragment may be comminuted. Type 4 is extension of the fracture through the epiphyis of the tibia. Type 5 is avulsion of the patella tendon and periosteum from the tibial tuberosity.

Associated injuries such as collateral and cruciate ligament tears, avulsion of tibialis anterior, meniscal damage or lateral plateau fractures should be considered. Treatment is either closed (types 1and 2) or open (types 3-5) reduction and a cylinder cast for 6 weeks.

Complications include screw prominence with associated

bursitis, compartment syndrome, loss of motion, refracture, genu recurvatum and leg length discrepancy.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Bilateral Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fractures

Liscense

Figures

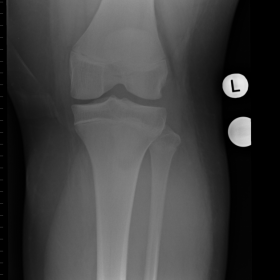

Left Knee. Type III tibial tubercle avulsion fracture.

Left knee. 2 months following fixation.

Right Knee. Type III tibial tubercle avulsion fracture.

Right knee 3 weeks following fixation.

Figure 5. Classification of Tibial Tubercle Avulsion fractures.

Radiological Findings

Based on the provided bilateral knee X-ray images, there are clearly visible fracture lines and fragments at both tibial tuberosities. Local displacement can be observed with internal fixation (screws) indicating reduction.

In the lateral view, the fracture fragment of the tibial tuberosity is displaced anterosuperiorly, consistent with an avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity.

Local soft tissue swelling is limited, and there is no sign of extensive soft tissue or joint effusion that would require immediate intervention. However, potential injuries to ligaments, menisci, and other soft tissues should still be considered.

Comparison between left and right knee images shows similar fracture patterns, indicating bilateral tibial tuberosity avulsion fractures, which is a relatively rare bilateral abnormality.

Potential Diagnoses

1. Tibial Tuberosity Avulsion Fracture (Acute Avulsion Fracture):

· Commonly seen in adolescents where the quadriceps muscle is strong and the tibial tuberosity is in the apophyseal stage. Sudden force (such as a strong contraction of the quadriceps or an abrupt flexion-extension of the knee) can easily lead to an avulsion at the tuberosity.

· X-ray findings typically involve the physis or tuberosity region with visible fracture lines and displacement, consistent with the images in this case.

2. Osgood-Schlatter Disease:

· More common in adolescent males, typically presenting as a chronic traction injury rather than an acute fracture. Patients often have recurrent pain and swelling at the tibial tuberosity, and imaging may show bony prominence or small fragments but not necessarily a distinct acute fracture line.

· In this case, the imaging clearly shows an avulsion fracture with displacement at the tibial tuberosity, indicating an acute fracture rather than simple Osgood-Schlatter disease.

3. Patellar Tendon Tear or Injury:

· A tear at the patellar tendon itself may appear as a soft tissue separation at the tibial tuberosity on imaging. However, in this case, the radiographic findings clearly demonstrate a bony avulsion with separation from the physis, consistent with a fracture rather than a primary patellar tendon rupture or injury.

Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s adolescent age, the bilateral knee injury mechanism (jumping or sudden flexion-extension), and the radiological findings (obvious avulsion fracture at the tibial tuberosities with fragment displacement and evidence of internal fixation), the most likely diagnosis is: Bilateral Tibial Tuberosity Avulsion Fractures (Acute Traumatic Tibial Tuberosity Fractures).

Treatment Plan & Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Strategy:

· If the fracture displacement is minimal (often Type I or II), conservative management may be considered, including immobilization with a cast or brace to avoid weight-bearing;

· For fractures with significant displacement or those involving the articular surface (Type III and above), surgical reduction and internal fixation (as shown with screws in this case) is often required, followed by cast or brace immobilization for approximately 6 weeks to facilitate bone healing.

· Vigilance for possible complications is necessary, such as early compartment syndrome, and later issues like limited range of motion or refracture.

2. Rehabilitation / Exercise Prescription:

(1) Immobilization and Early Recovery Phase (0–6 weeks post-op)

· The knee is typically immobilized in a cast or brace at a suitable degree of flexion or extension, with weight-bearing restrictions as advised by the physician;

· During this period, isometric quadriceps exercises and ankle/hip joint activities can be performed to maintain lower-limb muscle strength and circulation;

· Monitor the surgical wound and fixation to avoid excessive movement leading to displacement or delayed healing.

(2) Functional Recovery Phase (6–12 weeks)

· After gradual removal of the immobilization, begin joint range-of-motion exercises under professional supervision, progressing from passive to assisted into active flexion and extension;

· Partial weight-bearing walking may be introduced, alongside lower-limb strengthening exercises (e.g., straight leg raises, seated knee extension) with an incremental increase in intensity;

· Maintain training 3–4 times per week for 20–30 minutes per session, gradually increasing intensity and range of motion.

(3) Strengthening and Return-to-Sport Phase (after 3 months)

· Based on fracture healing and joint function, progressively incorporate low-impact aerobic exercises such as jogging, cycling, or swimming;

· Focus on strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, iliotibial band, and other core lower-limb muscle groups, gradually introducing jumping and pivoting exercises under professional guidance and assessment;

· Continue a regimen of 3–5 training sessions per week, monitoring the knee for excessive pain or swelling.

Throughout the rehabilitation process, the exercise plan should be adjusted according to individual progress. Radiological follow-up (X-rays) and clinical examinations are advised to ensure proper fracture healing and functional recovery. In case of severe pain, increasing dysfunction, or new injury, prompt medical consultation is necessary.

Disclaimer: This report is intended for reference only and does not substitute for a face-to-face consultation or a professional doctor’s clinical opinion. Please consult an orthopedic specialist or a relevant healthcare facility for specific diagnosis and management.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Bilateral Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fractures