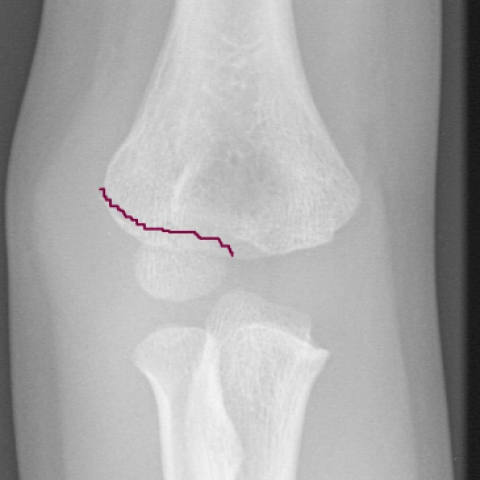

Paediatric lateral humeral condyle fracture

Clinical History

The elbow joint in children is complex, with multiple ossification centres and a large cartilaginous analogue making it difficult to diagnose fractures around it. We present a case of lateral condyle humerus fracture in a 5 year old. We discussed the difficulty to appreciate the displacement and the treatment options.

Imaging Findings

Case History:

A 5 year old girl fell off the bike and landed on her right elbow. She presented to the Accident and Emergency department (AED) with painful swollen elbow with restricted movements. Clinical examination revealed generalised swelling around the elbow joint with specific tenderness over the lateral condyle of the humerus. There was no distal neurovascular deficit. Antero posterior and lateral radiographs of the elbow were obtained (Fig 1,2). The fracture was missed initially and the patient was sent home with collar and cuff. However because of persistent pain, parents brought her back to AED. She was reviewed by orthopaedic team and identified as lateral humeral condyle fracture. She has been treated conservatively in plaster with regular follow-up and radiographs every week. The total duration of treatment was 6 weeks following which she was pain free.

Discussion

Lateral humeral condyle fracture in children is the second most common fracture around the elbow joint next to supracondylar fracture. Most of the fractures occur as isolated injury. They commonly occur between the ages of 4-10 years with peak incidence around 6 years. The usual mechanism of injury is varus stress to an extended elbow with forearm in supination (pull-off theory) or a blow to palm with flexed elbow (push-off theory) [4].

The distal humerus is mostly cartilaginous at the time these fractures typically occur. Due to incomplete ossification, the fracture fragment size and displacement appears smaller on the radiographs than the actual size, and articluar surface incongruity is present (Fig 2,3). These fractures are difficult to diagnose and commonly missed in AED because of this fact.

The key signs in diagnosing lateral condylar fracture include localised swelling, tenderness over lateral condyle. With non-displaced fractures these signs may be subtle, leading to delay in diagnosis. Antero-posterior and lateral radiographic views should be examined for any visible fracture or ‘fat –pad’ sign if the fracture is not visible. It is not uncommon to misinterpret the size, dislocation and rotation of the fracture fragment as it courses through cartilage analogue. If in doubt an oblique film should be obtained to view the fracture site more clearly. Arthrograms, MRI and ultrasound scanning are other alternatives [4]. MRI scan may be better in diagnosing the integrity of cartilage hinge which is believed as a major determinant of the stability of the fracture [5]. Chapman et al described the accuracy of Multidetector Computerised Tomogram (MDCT) in detecting degree of displacement and integrity of lateral soft tissue hinge [6].

Milch in 1964 identified the importance of these fractures in elbow stability and classified them into two groups based on the anatomical position of the fracture [1]. In Milch type I fracture, the fracture line courses lateral to trochlea and passes through capitello-trochlear groove (simple fracture). In type II injury fracture extends into the apex of trochlea (fracture-dislocation). They could be considered as a variant of Salter-Harris type lV and equivalent of Salter-Harris type II respectively and thence the injuries follows physeal injury principles.

Jacob et al classified the lateral condylar fractures in to three stages in relation to degree of displacement and rotation of fracture fragment. Some authors believe that it is more useful than Milch classification system [2]. Stage I is less than 2mm of displacement with an intact articular surface. Stage II is 2-4mm of displacements with moderate displacement of articular surface and stage III is with significant displacement and rotation of the fragment [2].

For practical purposes the fractures are grouped as displaced (>2mm) and undisplaced (<2mm). Displaced fractures treated operatively and undisplaced fractures treated non-operatively. Results of lateral condylar fractures are good when treated timely and appropriately. Complications occur due to biological problems or technical problems arising from management errors [3] are spur formation (30%), cubitus varus/ valgus non-union, malunion, ulnar nerve pals, physeal arrest and myositis ossificans.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Paediatric lateral condyle humerus fracture

Liscense

Figures

AP Radiograph

Lateral radigraph

The diagrammatic representation of fracture

1. Imaging Findings

Based on the provided anteroposterior (AP) and lateral X-ray images of the elbow, the following findings are noted:

• There is an interruption of the cortical continuity in the lateral portion of the distal humerus, with the fracture line located near the lateral condyle; signs of separation between the epiphysis and the main shaft are visible.

• The fracture line is relatively thin, and because the epiphysis in this age group is not fully ossified, the actual size and shape of the fracture fragment may be underestimated on the X-ray.

• On the AP view, there appears to be a slight displacement of the fracture fragment in the lateral-superior direction (it is difficult to precisely measure the degree of displacement on plain X-ray). The lateral view also shows disruption of the cortex in the lateral condyle region.

• Surrounding soft tissue swelling is present, especially on the lateral side of the joint, indicating an acute traumatic response in that area.

2. Potential Diagnoses

Based on the imaging findings and clinical history (a 5-year-old girl with lateral humeral pain and swelling after a fall), the following diagnoses are considered:

1) Lateral condyle fracture of the humerus: A common fracture in children around the elbow, typically presenting with a fracture line in the lateral condyle region, consistent with the mechanism of injury and local signs.

2) Radial head or neck fracture (differential diagnosis): If significant lateral swelling of the elbow is observed, the possibility of a radial head (neck) fracture should be excluded; however, this case more strongly suggests a lateral condyle fracture.

3) Other types of distal humeral physeal injuries: For instance, fractures involving the cartilage surface or the articular surface, which may require further imaging (CT, MRI, or arthrography) for evaluation.

3. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age, mechanism of injury, and imaging findings, the most likely diagnosis is: Lateral condyle fracture of the humerus (Jacob Stage I–II or a similar classification).

If further imaging studies (CT or MRI) reveal displacement greater than 2 mm or disruption of the cartilaginous hinge, it would be deemed an unstable fracture requiring surgical intervention. If the displacement is less than 2 mm and the cartilaginous hinge is intact, conservative management can be considered.

4. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

(1) Treatment Strategy

• Conservative treatment: For stable lateral condyle fractures with less than 2 mm of displacement, a cast or brace can be used for 4–6 weeks. Regular X-ray follow-ups are necessary to monitor fracture healing.

• Surgical treatment: If the fracture displacement is ≥ 2 mm, shows instability, or suggests cartilaginous hinge disruption, surgical exploration and reduction with Kirschner wire or tension band fixation is indicated. Screw fixation may be employed if needed to ensure proper joint surface alignment.

(2) Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription

Adopt a stepwise approach to rehabilitation once the fracture has stabilized or immobilization is removed. Specific guidelines may follow the FITT-VP principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, Progression):

1) Early Stage (initial period after immobilization)

• Frequency: 1–2 times per day of gentle exercises.

• Intensity: Focus on passive or active-assisted exercises, avoiding pain irritations.

• Time: 5–10 minutes each session, gradual progression.

• Type: Range-of-motion exercises starting with gentle flexion-extension of the elbow and forearm rotation.

• Progression: Increase activity range and frequency once pain subsides and fracture healing shows stable progress.

2) Middle Stage (improving range of motion)

• Frequency: 3–4 times per week, or as prescribed by a physical therapist.

• Intensity: Gradually increase active exercises; light resistance exercises can be introduced in a pain-free range.

• Time: 10–15 minutes each session, alternating activity and rest.

• Type: Increase joint mobility and muscle strength training; moderate use of grip balls or resistance bands as tolerated.

• Progression: Once the elbow range of motion meets functional demands, gradually add light weight-bearing exercises (e.g., light dumbbells, exercise bands) while avoiding excessive stress or reinjury.

3) Late Stage (functional strengthening and return to daily activities)

• Frequency: 3–5 times per week, adjusted according to functional requirements.

• Intensity: Progress to moderate intensity, emphasizing coordination, flexibility, and balanced strength training.

• Time: 15–20 minutes per session, or adjusted based on individual tolerance.

• Type: Under professional guidance, introduce throwing, weight-bearing, and other comprehensive upper limb functional exercises.

• Progression: Allow adequate adaptation time between increases in load or activity, monitoring joint stability and muscle strength recovery.

5. Disclaimer

This report is a reference analysis based on the available imaging and clinical information and does not replace an in-person consultation or a professional medical opinion. Diagnosis and treatment plans should be tailored to the patient’s actual condition under the guidance of an orthopedic specialist.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Paediatric lateral condyle humerus fracture