A 41-year-old female with localized increasing lower back pain without history of direct trauma.

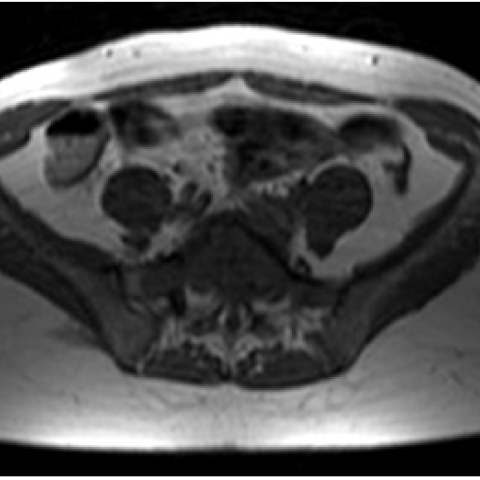

A 41-year-old female presented with severe pain in the lumbar region, weakness and limited range of motion lasting from over one month, without history of direct trauma. MR of the lumbosacral spine (Fig. 1) revealed collapse of the fifth sacralized vertebra which appeared diffusely enlarged and partially replaced by tissue of low signal intensity on T1-/T2-weighted images and high signal intensity on STIR sequences, involving the vertebral body, pedicles and part of the laminae without extension into the spinal canal.

The CT examination confirmed the collapse and diffuse enlargement of L5 vertebral body and pedicles, because of a large osteolytic lesion determining a diffuse thinning of the cortex (Fig. 2, 3). The vertebral body appeared replaced by parenchymatous tissue enhancing after contrast medium administration, particularly during the venous phase (Fig. 4). The CT-guided biopsy (Fig. 5) and histologic analysis of the lesion confirmed the diagnosis of giant cell tumour.

Giant cell tumour (GCT) is a relatively common skeletal tumour, accounting for 4-9.5% of all primary osseous neoplasms and 18-23% of benign bone neoplasms. GCT is typically benign and solitary and, in this case, affects women more commonly than men. However, multiple lesions have been described and 5%-10% of lesions may be malignant.

The single most common site of GCT is the distal femur, followed by the proximal tibia, distal radius, sacrum and proximal humerus.

Vertebral localization is quite rare. Most of these lesions occur in the sacrum, followed in order of decreasing frequency by the thoracic, cervical, and lumbar segments. Spinal lesions demonstrate an even higher female predilection and affect patients in their second to fourth decades of life. The vertebral body is usually involved with the lesion growing eccentrically. An important feature is the ability of the lesion to grow across the sacroiliac joint or cross a disc space.

GCT radiography typically shows a lytic lesion with cortical expansion. A purely osteolytic pattern is also possible. Cortical thinning of bone is invariably apparent at radiography.

CT and MR imaging allow superior delineation and staging of GCTs.

CT demonstrates the absence of mineralization and the lack of a sclerotic rim at the margins of the tumor. It also improves detection of cortical thinning, pathological fracture, and periosteal reaction.

At MR study the tumour usually presents as a well-defined lesion with a low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Areas of high signal intensity can suggest relatively recent haemorrhage. More specifically, most giant cell tumours of the spine have low to intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images. This appearance seems to be caused by hemosiderin deposition and high collagen content. Although this feature is not unique to giant cell tumours of the spine, it is quite helpful in making a differential diagnosis because most other spinal neoplasms (metastases, myeloma, lymphoma, and chordoma) show high signal intensity on the long-TR MR images. Enhancement of the lesion reflects its vascular supply. Cystic areas, foci of haemorrhage, fluid-fluid levels, and a peripheral low-signal-intensity pseudocapsule may also be seen.

GCTs of the spine should be completely removed; because of their location, however, this usually means excision with an intralesional margin. Lesions with extension into the spinal canal and paraspinous space have slightly higher recurrence rates. Because of the risk of sarcomatous transformation, radiation therapy should be reserved for patients with incomplete excision or local recurrence.

Giant cell tumor of lumbar spine

This case involves a 41-year-old female patient presenting with progressively worsening lower back pain, without a history of trauma. Analysis of the provided CT and MRI images shows:

Considering the patient's age, symptoms, and imaging features, the following differential diagnoses are proposed with their respective rationales:

Integrating the imaging features (lytic lesion, cortical expansion, low-to-intermediate T2 signal on MRI with possible hemorrhagic or cystic components) alongside the patient’s age and clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is:

Giant Cell Tumor of the Sacrum.

A biopsy is recommended for a definitive histopathological diagnosis. If the pathological findings are consistent with the imaging, diagnosis can be confirmed. Further differentiation from chordoma or metastatic disease may be required if imaging or pathology findings are atypical.

After treatment or during the perioperative period, individualized and progressive rehabilitation therapy is essential to promote functional recovery and prevent complications. The following FITT-VP principles may be referenced:

Additional considerations include:

Disclaimer: This report provides a reference-based medical analysis based on the information provided and does not replace in-person consultations or professional medical advice. If you have any concerns or changes in your condition, please seek prompt evaluation from a specialist.

Giant cell tumor of lumbar spine