Abnormal pelvic radiograph in a 55-year-old lady with lethargy and mood disturbances.

A 55-year-old lady was referred to the rheumatology out-patients clinic with an abnormal pelvic radiograph and an 8 month history of lethargy, anorexia, polydipsia and polyuria. The patient was also being treated for a mood disorder by her psychiatrist. She was also being treated for chronic gastritis and hypertension. A thorough clinical examination revealed a lump on the left side of her neck. Elevated serum calcium and parathyroid hormone were found.

The rheumatologist requested radiographs of the skull, hands and pelvis. Symmetrical subperiosteal bone resorption in the proximal, middle and distal phalanges (Fig. 1) was seen in both hands. The pelvic radiograph (Fig. 2a) showed three well defined radiolucent lesions with a narrow sclerotic zone of transition in the acetabular portion of the left iliac bone. No periosteal reaction or soft tissue component was evident around these lesions on CT (Fig. 2b). The appearance of these lesions was highly suggestive of ‘Brown tumours’, which consist of localised replacement of bone by vascular fibrous tissue secondary to parathyroid hormone induced osteoclastic bone resorption.

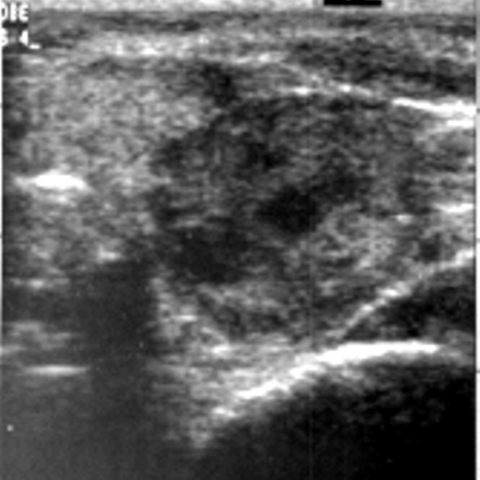

The patient had an ultrasound of her neck (Fig. 4a), which showed an 8 cm ovoid hypoechoic lesion of heterogeneous echotexture posterior to the left thyroid lobe. No cervical lymphadenopathy was seen. The lesion was not involving the adjacent structures – this was confirmed on CT (Fig. 4b).

An ultrasound guided core biopsy of the neck lesion revealed a parathyroid adenoma.

Hyperparathyroidism is defined as an uncontrolled production of parathyroid hormone, which causes an increase in the serum alkaline phosphatase, elevated serum calcium and decreased serum phosphate. This initially results in an increased bone mass, and is later followed by bone resorption.

Since today hyperparathyroidism is detected early, fewer patients with less bone are identified as in former times. The symptoms are all related to the hypercalcaemia: muscular hypotonicity, lethargy, confusion, depression, constipation, dysphagia, peptic ulcer disease, polyuria, polydipsia, nephrocalcinosis. The adage ‘moans, bones, stones and groans’ as an aide memoire for hypercalcaemia still holds. Brown tumours represent relatively late complication of excess parathyroid hormone and represent sites of bone weakness.

Bone involvement is a late manifestation of hyperparathyroidism occurring with a frequency of 1.5 – 1.75% in secondary and 3-4% in primary hyperparathyroidism. The aetiology is a parathyroid adenoma (87% of cases), parathyroid hyperplasia (10%) and parathyroid neoplasms are present in 3% of cases.

Classic skeletal lesions, namely bone resorption, bone cysts, brown tumours and generalised osteopenia, occur in less than 5% of cases. The term ‘brown tumour’ comes from the colour of the lesion, resulting from the vascularity, haemorrhage and deposits of haemosiderin. It is often present in multiple bones as an expansive osteolytic lesion which shows increased isotope uptake on bone scan. Brown tumours are non-neoplastic, resulting from abnormal bone metabolism in hyperparathyroidism and represent the terminal stage of bone remodelling. Radiographic features of hyperparathyroidism include subperiosteal, peritendinous, cortical endosteal and subchondral bone resorption and generalised loss of lamina dura surrounding roots of teeth and loss of cortication around the inferior alveolar canal. Subperiosteal bone resorption occurs along the bony cortex and is virtually pathognomonic of hyperparathyroidism.

The pathology of brown tumours involves localised replacement of bone by vascularised fibrous tissue, called osteitis fibrosa cystica, since lesions may become cystic following necrosis and liquefaction. They are often found in the jaw, maxilla, pelvis, rib, metaphyses of long bones, facial bones and have a predilection for the axial skeleton. Brown tumours are expansile lytic well-marginated cyst-like lesions. Their differential diagnosis includes giant cell tumours or granulomas, enchondromas, aneurysmatic cysts, cherubism, Paget’s disease, odontologic bone tumours and nonodontologic fibrous dysplasia. However, the latter conditions do not show adjacent reactive bone formation, endosteal scalloping and destruction of the midportions of the distal phalanges with telescoping, typical of brown tumours.

Treatment depends on location and symptomatology. Surgical excision is indicated for large, disfiguring lesions and cases where the bone is significantly weakened with high risk of pathological fractures. They are not usually painful unless compressing neighbouring structures. In most cases, when the growth of the tumour is closed and its position is not causing morbidity, surgical treatment is not indicated. Rehydration and pharmacological treatment with bisphosphonates and SERMs is indicated and timely subtotal/total parathyroidectomy is reserved for non-responders or patients with functional problems including mastication and with lesions restricting mobility. The proper timing of parathyroidectomy and its effect on regression of brown tumours makes it possible to avoid potentially disfiguring surgical removal.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

Based on the provided X-ray images of both hands and the pelvis, as well as certain CT slices, the following major features are observed:

Combining the patient’s age (55-year-old female), clinical symptoms such as fatigue and depressed mood, and radiological findings of osteolytic lesions and bone resorption, the following diagnoses are worth considering:

Taking into account the patient’s age, clinical symptoms (fatigue, depressed mood, etc.), possible laboratory findings (if suggesting hypercalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and elevated PTH), and the above radiological features, the most likely diagnosis is:

“Hyperparathyroidism (possibly primary) with Brown Tumors”

Further confirmation can be obtained through laboratory tests (serum calcium, phosphate, and PTH levels), as well as neck ultrasound or parathyroid scintigraphy to determine the cause (e.g., adenoma). For suspicious skeletal lesions, a biopsy could be considered to rule out other osteolytic tumors.

Because hyperparathyroidism can lead to weakened bones, rehabilitation should be tailored to individual fitness levels, progressively restoring muscle strength and bone density while avoiding excessive impact.

Throughout rehabilitation, take precautions to prevent falls and ensure safety. Under professional guidance, perform appropriate muscle-strengthening or joint-mobilization exercises to prevent fractures or further bone loss.

This report is based on the existing imaging and clinical history for reference only. It cannot replace in-person evaluations or professional medical advice. Specific treatment must be determined by combining clinical examination with assessment and recommendations from relevant specialists.

Primary hyperparathyroidism