Granular cell tumour of the buttock

Clinical History

A 49 year old African-American woman with a history of a slowly growing soft tissue mass over the right gluteal region for the past 6 months. No complaints of radicular pain, numbness, or discomfort. No systemic symptoms such as fever or weight loss.

Imaging Findings

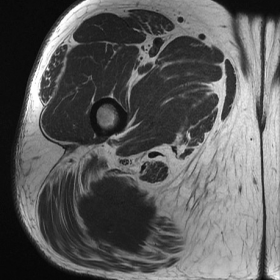

MR images show an irregular soft tissue mass within the right gluteus maximus measuring up to 6.6 cm in maximum dimension. The lesion is separate from the sciatic nerve by an intact fat plane and does not extend beyond the gluteus maximus. The mass is isointense to muscle on T1- and hypointense on T2-weighted images. It heterogeneously enhances after the administration of gadolinium.

Multiple passes from ultrasound core needle biopsy were performed, returning a pathologically proven diagnosis of a benign granular cell tumour.

Discussion

Granular cell tumours (GrCTs) were first described in 1926 by Abrikossoff [1], and initially thought to arise from muscle. They were originally referred to as granular cell myoblastomas, but were renamed as they are now known to be of neural origin, arising from Schwann cells [2]. GrCTs are rare, accounting for 0.5% of all soft tissue tumours [3].

Most GrCTs are benign but in 1-3% of cases they are malignant [4]. They can occur anywhere in the body, but are most commonly found in the tongue, skin, and subcutaneous tissues [5], and can be multifocal at the time of presentation (5-16% of cases)[6]. GrCTs often present as a painless mass between the third and fifth decades of life, and are more common in women and in African Americans [2].

Fanburg-Smith et al. [4] described six histologic criteria that are important in predicting malignant behaviour. These include necrosis, cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, increased mitotic rate (>2/10 high power fields), high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and pleomorphism. If a tumour has three or more of these features, it is classified as malignant; if 1 or 2 criteria are fulfilled, it is classified as atypical, and if the tumour shows none of these features it is classified as benign [4].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important for diagnosis and preoperative planning. There are only a few small case series that describe the MR appearance of both benign and malignant GrCTs. Benign GrCTs are classically round or oval in shape, superficial in location, and generally less than 4 cm in size [7]. Benign GrCTs are heterogeneously low in signal intensity on T1 and T2- weighted images [7-9]. A peripheral rim of high signal on T2-weighted images may be present. Malignant GrCTs may demonstrate invasion of adjacent structures, areas of necrosis and a lobulated irregular contour [7]. The signal characteristics of malignant lesions are signal isointense to or slightly higher than muscle on T1-weighted sequences and variable in signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences.

The low signal intensity on T2-weighted images is secondary to low cellularity and increased collagen content, which can be a distinguishing characteristic, as the majority of soft tissue tumours have intermediate to high signal on T2-weighted images. Other lesion with low signal intensity on T2-weighted images include: desmoid tumour, desmoplastic fibroblastoma, and fibromatosis. However, malignant granular cell tumours should also be considered in the differential.

Enhancement patterns of both benign and malignant GrCTs are variable and not well documented within the literature [7,10]. However, Osanai et al. [10] demonstrated that the enhancing regions corresponded to highly cellular regions, suggesting that the enhancing portions of the tumour should be the target sites for biopsy.

Radiation and chemotherapy is ineffective and the best treatment modality is early wide surgical resection. In patients with benign and atypical lesions, wide excision is generally curative [8]. However, the prognosis for malignant GrCTs is poor with a median survival of roughly 3 years [4]. In summary, MRI and histologic criteria are useful in the diagnosis of GrCTs and importantly, in differentiating benign from malignant types.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Right gluteus maximus benign granular cell tumour.

Liscense

Figures

Axial T1WI.

Axial T1WI post gadolinium.

Sagittal T2WI.

Sagittal STIR.

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

1. Imaging Findings

The patient in this case is a 49-year-old female who has presented with a slowly growing soft tissue mass in the right buttock for 6 months. MRI shows a well-defined soft tissue lesion located in the subcutaneous/muscular interspace of the right buttock. The specific imaging characteristics are as follows:

• On T1-weighted imaging, the lesion signal is slightly lower or similar to the muscle signal.

• On T2-weighted imaging, the lesion generally exhibits low signal, with a local or marginal mild hyperintense rim.

• The lesion is roughly round or oval in outline, with no obvious destruction of adjacent bone structures or deep muscular infiltration.

• No evident necrosis or liquefaction is observed within the lesion.

2. Potential Diagnoses

Based on the above imaging findings and the patient’s history, the following diagnoses or differential diagnoses should be considered:

(1) Granular Cell Tumor (GrCT)

— Granular cell tumors are commonly seen in patients aged 30–50 years, more frequently in females and non-Caucasian populations. They often occur in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or tongue and typically appear low signal on T2-weighted images; most are benign.

(2) Desmoid Tumor or Other Fibrous Lesions

— Such lesions may show low to isointense signals on T2-weighted imaging. They are histologically rich in collagen fibers, grow slowly, and may be related to trauma, hormonal levels, or genetic factors.

(3) Malignant Granular Cell Tumor

— Although rare, about 1–3% of granular cell tumors may be malignant. If a lesion has an irregular boundary, shows apparent infiltration or necrosis, or if histological findings meet ≥3 of the malignancy criteria proposed by Fanburg-Smith, a high suspicion for malignancy is warranted.

3. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age, clinical history (slow growth without significant pain or systemic symptoms), imaging characteristics (iso- to slightly low signal on T1, low signal on T2, and no obvious invasion of adjacent tissues), and histological report (if biopsy/surgical pathology indicates neural sheath origin), the most likely diagnosis is benign granular cell tumor (Granular Cell Tumor).

If it is necessary to rule out malignant or atypical types, a biopsy can be performed to obtain histopathological evidence and confirm whether it meets the malignancy criteria established by Fanburg-Smith and others.

4. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Treatment Strategy:

• Surgical Treatment: For benign or suspicious granular cell tumors, a wide-margin surgical resection is the first-line treatment to minimize the risk of local recurrence. If postoperative histology confirms a malignant granular cell tumor, close follow-up is necessary and further resection may be required.

• Other Treatments: Radiotherapy and chemotherapy generally have limited effectiveness for granular cell tumors and are usually reserved as adjunct or palliative treatments in cases of inoperable or metastatic malignancy.

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP Principle):

• Early Postoperative Phase:

- Engage in light activities of the affected buttock or lower limb as permitted by the physician, avoiding excessive stretching or tension.

- Frequency: 1–2 times per day, short-duration, low-intensity training.

- Intensity: Low intensity, such as simple hip and knee flexion and extension exercises in bed or while seated.

- Time: Each session should last about 5–10 minutes.

- Type: Passive or assisted active exercises; avoid excessive pulling on the surgical incision.

- Progression: Gradually increase self-directed movement and maintain joint mobility depending on wound healing and pain tolerance.

- If no complications arise, gradually introduce light to moderate functional exercises, such as transitioning from seated to standing positions and short-distance walking.

- Under the guidance of a physical therapist, gentle gluteal strengthening exercises (e.g., bridge exercises, side-lying leg raises) may be added.

- Each session can be extended to 10–15 minutes, 2–3 times per day, or adjusted based on individual tolerance.

- As muscle strength and postural stability improve, progressively increase resistance or weight-bearing exercises.

- The goal is to restore normal gait, hip joint function, lower limb strength, and flexibility.

- Incorporate aerobic exercises (e.g., stationary cycling) or low-impact activities (e.g., swimming) to enhance overall cardiovascular fitness.

5. Disclaimer

This report is based solely on the existing medical imaging and clinical information and is for reference only. It cannot replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. Specific diagnosis and rehabilitation plans should be formulated based on the patient’s actual condition and evaluated by relevant specialists and rehabilitation therapists.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Right gluteus maximus benign granular cell tumour.