Distal femoral cortical irregularity in an adolescent

Clinical History

A 14 year-old asymptomatic male was referred for second opinion of a left femoral lesion detected in a radiograph.

Imaging Findings

A 14 year-old asymptomatic male was referred for second opinion of a left femoral lesion. The radiographs of the left knee revealed a cortical irregularity projected on the posterior aspect of the supracondylar left femoral metaphysis, only apparent on the lateral view (Fig. 1).

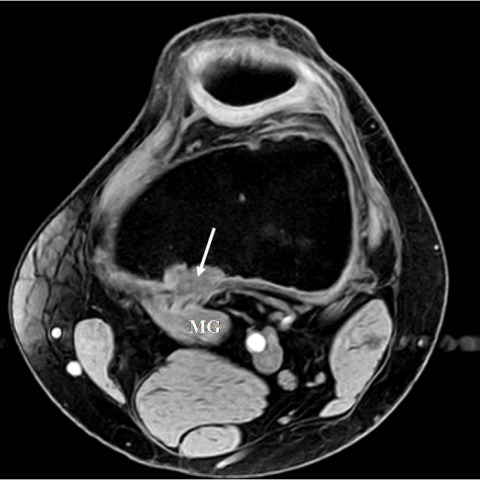

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee (Fig. 2) demonstrated an ovoid cortical lesion on the posterior and medial aspect of the supracondylar left femoral metaphysis, located at the attachment of the medial head of the left gastrocnemius muscle. The lesion had low signal on T1 weighted-images (WI) (Fig. 2 a) and intermediate to high signal on T2-WI and gradient-echo (GRE) water-excited sequences (Fig. 2 b and 2 c).

The patient's age, the typical location, and the imaging findings were suggestive of cortical avulsive irregularity, also know as Bufkin lesion or cortical desmoid. The adolescent and his parents were reassured and no treatment was instituted.

Discussion

Avulsive cortical irregularity (ACI) is a relatively common radiologic finding (3,6-11,5% incidence), best understood as a diagnostic challenge. ACI corresponds to a reactive fibro-osseous non-tumoural proliferation believed to be related to chronic traction exerted by the adductor magnus aponeurosis or the medial head of the gastrocnemius at their attachment. ACI’s alternative designations include, Bufkin lesion or cortical, periosteal, or parosteal-juxtacortical desmoid. However it should be noticed that the term desmoid is misleading as implies a tendency to recur after excision whereas ACI is a benign and self-limited condition that heals with skeletal maturity and is rare after the age of 20.

ACI predominantly affects males and adolescents. It is most commonly asymptomatic, although minimal localised pain or soft-tissue swelling, sometimes after a trauma, have been reported.

ACI is typically located in the posteromedial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis and is bilateral in one third of cases. In counterdistinction to fibrous cortical defect, which ACI may mimic, ACI typically remains at its original site through growth.

Radiographic visualisation of ACI is best achieved by an oblique view in external rotation. A sauce-shaped cortical defect with sclerosis or cortical roughening in the typical location is very suggestive. Three morphological types have been described concave, convex, and divergent, with the cortex appearing split and widened in the latter.

ACI’s typical radiographic findings in the characteristic age establish the diagnosis, precluding further work-up. On the other hand, ACI is a common finding that can be incidentally observed in other imaging techniques and that radiologists must be aware of.

ACI's appearance on nuclear imaging depends on maturity, varying from normal or slightly increased focal uptake in active stage to absence in inactive lesions.

CT and MRI although not required for diagnosis are helpful in radiographic equivocal or atypical cases. They are more accurate for ACI detection, more precisely trace its location and exclude an associated soft-tissue mass. CT more precisely assesses lytic or thickened cortical areas and associated minor fragmentation.

MRI typically shows a well-defined cortically based lesion with low to intermediate signal intensity (SI) on T1-WI and intermediate to high SI on T2-WI depending on the relative amount of hypercellular fibrous tissue, hemosiderin, collagen, foamy histiocytes, and bone trabeculae. A surrounding rim of low SI, most likely representing marginal sclerosis, is more apparent on T2-WI. Lesion enhancement, subtle soft-tissue oedema, and localized marrow oedema may also be seen.

ACI is a “don’t touch lesion” and its diagnosis should be established noninvasively as histologically it may be difficult to distinguish from other fibrous or fibro-osseous proliferative entities such as osteosarcoma, aggressive fibromatosis, or desmoplastic fibroma.

Imaging clues to the correct diagnosis are the classic location; a history of strenuous physical activity; absence of permeative cortical destruction, of bone marrow disease, and of a soft-tissue mass, as well as stable to improving clinical and imaging progression.

Whether incidentally observed or as part of a focused diagnostic evaluation, ACI is a common finding. Clinical and imaging correlation allows noninvasive diagnosis, avoiding unnecessary and inappropriate biopsy and therapeutic actions.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Avulsive cortical irregularity (cortical desmoid or Bufkin lesion)

Liscense

Figures

MR of the left knee

Radiographs of the left knee

Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

Based on the X-ray and MRI data provided by the patient, the following characteristics have been observed:

- The lesion is located in the posteromedial cortex of the distal left femur, showing noticeable cortical irregularities.

- X-ray images reveal an irregular margin on the cortical surface, with mild indentation or a “shallow saucer-like” appearance. In certain views, localized sclerosis or coarse cortical texture can be seen.

- MRI indicates that the lesion is confined to the cortex and has well-defined boundaries. On T1WI, it demonstrates low to intermediate signal, and on T2WI, it shows intermediate to high signal with a relatively low signal rim, suggesting a mild sclerotic line. No significant soft tissue mass or bone marrow involvement is noted.

- No obvious bone destruction or erosion is seen in the lesion area, and there is no notable swelling or mass effect in the surrounding soft tissues.

- The patient is currently a 14-year-old male, presenting with no significant symptoms or only mild local discomfort, consistent with the imaging findings.

II. Possible Diagnoses

Taking into account the patient’s age, lesion location, and imaging presentation, the following diagnoses or differential diagnoses are considered:

- Avulsive cortical irregularity (ACI)

Commonly seen in adolescents with not fully mature skeletal systems, primarily due to repeated traction at tendon attachments leading to localized cortical changes. Radiographically, it typically presents as a shallow, irregular cortical depression on the posteromedial aspect of the distal femur near the joint, appearing benign and self-limiting. - Fibrous cortical defect

Similar to ACI in that it may show fibrous tissue changes on the cortex, but fibrous cortical defects are more commonly located in the metaphysis. They can also shift in position as the bone grows. - Osteosarcoma

A malignant tumor frequently seen in adolescents, which typically manifests as aggressive bone destruction, periosteal reaction, and soft tissue mass on imaging—features not consistent with this case. - Desmoid tumor or other fibrous proliferative lesions

Should be considered if the lesion extends into surrounding soft tissues with invasive features, but there is no evidence of a significant soft tissue mass or destructive changes in this instance.

III. Final Diagnosis

Combining the patient’s age, clinical presentation, and imaging findings, the most likely diagnosis is:

Avulsive cortical irregularity (ACI).

ACI commonly arises from repetitive traction at tendon insertion sites in adolescents, resulting in a benign, self-limiting fibrous-bone reaction. Currently, there is no sign of aggressive behavior, and invasive assessments are not indicated.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Treatment Strategies:

- Conservative observation: Given that ACI is typically self-limiting, most cases do not require surgery or biopsy. Periodic imaging follow-up is sufficient to monitor lesion progression.

- Pharmacological support: In cases of pain or inflammation, short-term use of NSAIDs may be considered. However, most patients experience minimal to no symptoms.

- Surgical intervention: If imaging or clinical features strongly suggest malignancy, or if the lesion continues to enlarge and causes significant symptoms, further biopsy and surgical management might be considered. Nevertheless, surgery is generally not recommended for typical ACI.

Rehabilitation / Exercise Prescription Recommendations (FITT-VP Principle):

- Frequency: Engage in low to moderate intensity physical activities (e.g., walking, swimming, light jogging) 3-5 times per week.

- Intensity: Maintain a perceived exertion in the easy to moderate range (around a 2-4 on a subjective scale), avoiding excessive traction on the affected muscles.

- Time: Aim for 20-30 minutes per session, adjusting total duration based on tolerance.

- Type: Opt for low-impact aerobic exercises such as swimming, cycling, or using an elliptical to reduce impact on the distal femur. Mild lower limb strength and flexibility training may be included.

- Progression: Gradually increase intensity and duration according to growth and symptom relief. If local pain or discomfort arises, modify or pause the activity plan promptly.

- Volume & Precaution: Weekly training volume should account for the patient’s skeletal development and joint stability. If discomfort persists or worsens, reduce or change activities and consult a physician or rehabilitation specialist.

Because the patient is still in a developmental stage, special attention should be paid to muscle attachment sites prone to traction or irritation. Repetitive overextension movements should be avoided. Any new or persistent pain or functional limitation should prompt immediate medical evaluation.

Disclaimer:

This report is based solely on the provided imaging and limited clinical history for preliminary analysis, to serve as a reference in clinical decision-making. It does not replace a face-to-face evaluation by a qualified physician. Specific treatment plans should be formulated by a specialist after comprehensive assessment of the patient’s individual situation.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Avulsive cortical irregularity (cortical desmoid or Bufkin lesion)