Giant cell tumour of bone involving a finger phalanx

Clinical History

A 22-year-old female with no significant history presents with pain and swelling of left middle finger for 13 months. Physical examination revealed fusiform swelling of the middle finger proximal phalanx, without a wound or erythema. Digital sensation was intact, with moderate limitation of finger flexion.

Imaging Findings

Radiographs of the left hand demonstrate an expansile lytic lesion of the proximal phalanx of the middle finger, with internal bony septations. The lesion extends to the proximal end of the phalanx. There is a large area of cortical disruption along the volar aspect of the lesion.

MRI shows an expansile, lobulated medullary lesion that is moderately hyperintense on STIR, with low signal internal septations. The lesion is slightly hyperintense to muscle on T1 and shows diffuse heterogeneous enhancement. Despite the volar cortical disruption, the mass does not invade the surrounding soft tissues.

Image from US-guided biopsy shows the biopsy needle within a uniform intermediate-echogenicity mass.

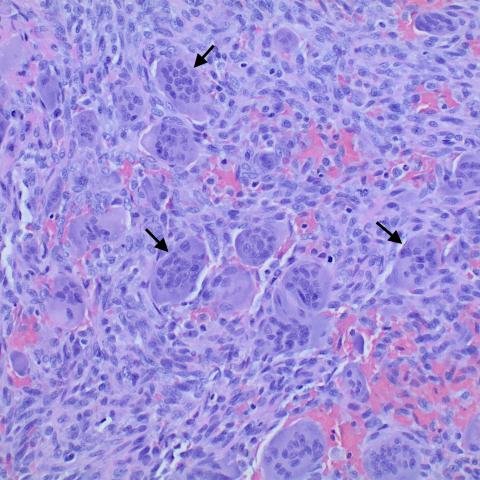

Histopathology images demonstrate numerous multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells, surrounded by mononuclear neoplastic cells.

Discussion

Giant cell tumour (GCT) of bone is a locally aggressive, rarely metastasizing benign osseous neoplasm. Histologically, GCTs are characterized by osteoclast-like giant cells and neoplastic mononuclear stromal cells [1]. At least 95% of GCTs demonstrate an H3F3A gene mutation. Malignant transformation occurs in <10% of giant cell tumours.

The majority of GCTs occur in patients 20-45 years old, with a slight female predominance. Pain and swelling are the most common presenting symptoms. GCTs are most common at the ends of the larger long bones of the extremities (femur, tibia, humerus, radius). GCT of the hand accounts for <5% of all GCTs [2] and <5% of all primary tumors of the hand [3].

Because of the osteoclastic nature of the giant cells, GCTs appear radiographically as lytic lesions, with expansion and disruption of the cortex. Endosteal ridging may result in internal septation/trabeculation. There is often a notable lack of sclerosis along the periphery of a GCT due to osteoclastic activity. Periosteal reaction is unusual in the absence of a pathological fracture.

On MRI, the appearance of GCT is non-specific. T1 and T2 signal intensity are variable, based on the presence of hemosiderin from prior hemorrhage or fibrosis. Fluid-fluid levels may be present in areas of aneurysmal change. With contrast, there is enhancement of the solid portions of the tumor.

GCT can be treated with surgical curettage, as in this case. Placement of cement impregnated with zoledronate helps to prevent local recurrence. Between 15% and 50% of GCTs develop local recurrence after curettage.

Written informed patient consent for publication has been obtained.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Giant cell tumour of bone

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Radiological Findings

Based on the imaging data of the patient's left middle finger (including X-ray and MRI, etc.), the following main features are observed:

1. X-ray: The proximal phalanx of the left middle finger shows a distinct expansile lucent area (lytic lesion) with visible septations (trabeculae or internal partitions). The local cortex appears thinned and even slightly eroded. There is no obvious surrounding sclerotic reaction, and no significant fracture is noted.

2. MRI: The lesion shows relatively mixed signals on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, possibly related to hemorrhage, fibrosis, or hemosiderin deposition. A fluid-fluid level is visible on certain slices, suggesting a cystic or aneurysmal component. Significant enhancement can be seen in the solid portions after contrast administration.

3. Ultrasound: Demonstrates a space-occupying lesion in the phalanx with a relatively well-defined boundary and relatively hypoechoic or mixed echogenicity. However, details of bone destruction are difficult to evaluate via ultrasound.

4. Histopathology: Under the microscope, numerous osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells (indicated by arrows) are distributed within the tumor stroma, along with proliferation of mononuclear stromal cells, consistent with the typical histological pattern of a giant cell tumor.

Potential Diagnosis

Given the patient's age (22 years old), prolonged local swelling and pain in the hand (13 months), the lytic changes seen on imaging, and the evidence of multinucleated giant cells on pathology, the primary differential diagnoses include:

1. Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) of Bone: Commonly observed in adults aged 20–45, typically occurring at the epiphysis of long bones. Radiologically, an expansile lytic lesion is often seen, and numerous osteoclast-like giant cells are present within the tumor. Pathological correlation is strong.

2. Aneurysmal Bone Cyst (ABC): Often found in adolescents, can also show an expansile lytic lesion with septations and fluid-fluid levels on imaging. Histologically, it frequently contains blood-filled spaces and sinusoid-like structures, but fewer multinucleated giant cells compared to GCT.

3. Cartilage-Origin Tumors (e.g., Enchondroma): Certain cartilaginous lesions in the hand may present with lytic changes, but imaging often reveals characteristic calcification or rings-and-arcs pattern. Pathologically dominated by cartilaginous cells, which differs from the high number of multinucleated giant cells found here.

Final Diagnosis

Based on the patient's clinical presentation, radiographic characteristics (notably the expansile lytic lesion with no obvious sclerotic rim), and histological findings (abundant osteoclast-like giant cells and neoplastic stromal cells), the most likely diagnosis is:

Giant Cell Tumor of Bone.

As pathology has confirmed the diagnosis, no other special examinations are deemed necessary at this time. However, close follow-up is required to assess the risk of tumor recurrence.

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Given the locally aggressive behavior and tendency for recurrence of giant cell tumors, surgical intervention is typically the mainstay of treatment. Considering this particular case, common approaches include:

1. Surgical Curettage and Lesion Filling: Thorough intraoperative removal of the lesion, potentially combined with high-speed burring around the lesion margins. Options may include using bone grafts or bone cement containing anti-recurrence agents (e.g., zoledronic acid) for filling.

2. Postoperative Medical Therapy: In cases with high risk of recurrence, adjuvant therapy may include local injection or systemic administration of bisphosphonates, denosumab (anti-RANKL antibody), or other emerging treatments, depending on postoperative pathology and clinical assessment.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription:

• Early Postoperative Phase (1–2 weeks): Perform gentle finger joint passive mobilization and muscle-strength exercises as tolerated by pain. Focus on finger flexion, extension, and gentle grip exercises, 3–5 times per day, 1–2 minutes each time, avoiding overextension or tissue damage.

• Intermediate Rehabilitation (3–6 weeks): Gradually increase active finger movement and range-of-motion exercises. Use a soft grip ball or resistance band for mild resistance training, increasing workload or duration by 10–20% weekly, provided there is no significant pain.

• Late Rehabilitation (after 6 weeks): Once bone healing and soft tissue recovery are confirmed, progress to higher-intensity small-muscle endurance and coordination exercises (e.g., light dumbbells, grip strengtheners). Increase load gradually, monitor joint range of motion and local swelling weekly, and adjust accordingly.

• If bone fragility or incomplete functional recovery persists around the perioperative period, avoid high-impact or heavy-load activities for the affected hand. Collaborate closely with rehabilitation specialists or orthopedic professionals for ongoing adjustments to training intensity and frequency.

Combining these treatments with individualized rehabilitation, following the FITT-VP principles (Frequency, Intensity, Type, Time, Volume, Progression), can gradually restore hand function and reduce the risk of tumor recurrence.

Disclaimer

This report provides a reference analysis based on the currently available information. It does not replace in-person consultation or the diagnosis and treatment advice of a professional physician. A definitive treatment plan should be formulated by qualified clinical doctors according to the patient's actual condition.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Giant cell tumour of bone