Bilateral ossification of the stylohyoid ligament: the Eagle syndrome

Clinical History

A 64-year-old Caucasian man, presented to the department of orthopaedics with persistent neck pain. History included a progressively deteriorating pain for 1 year and bilateral upper limb weakness and numbness. The physical examination revealed bilateral palpable, “cord-like” structures at the level of the hyoid bone.

Imaging Findings

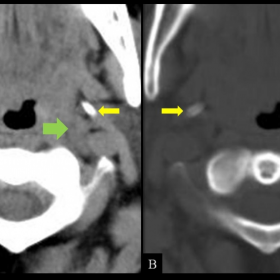

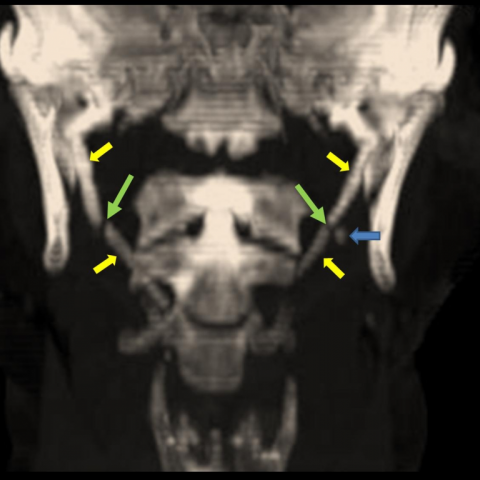

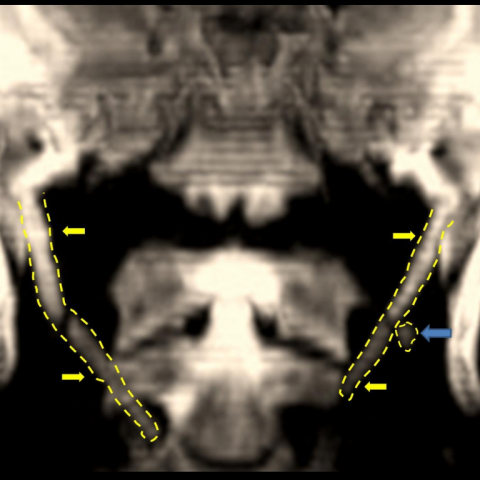

The neurologic examination revealed provocation of symptoms from the upper limbs with cervical movements and relief of symptomatology with the head in the neutral position. The patient was referred for a cervical CT scan. The MDCT examination demonstrated the presence of bilateral elongated styloid processes and ossification of the stylohyoid ligaments (Fig. 1). The MPR and VRT reformatted images confirmed the findings and in addition demonstrated pseudoarticulations between the ossified stylohyoid ligaments and the minor horns of hyoid bone as well as between the styloid processes and the stylohyoid ligaments (Fig. 2-4). The patient’s medical history in correlation with the clinical and radiologic findings suggested the diagnosis of Eagle’s styloid syndrome and surgical treatment was proposed. The patient refused surgery and remains symptomatic.

Discussion

In 1937 W. W. Eagle was the first who introduced the term “stylalgia” due to abnormal lengthening of the styloid process and due to calcification of the stylohyoid ligament complex. The elongated styloid process syndrome (Eagle syndrome) can occur unilaterally or bilaterally and most frequently presents with symptoms of dysphagia, head and neck pain especially on rotational movements, change in voice, painful tongue movements, otalgia and hypersalivation. The associated symptomatology is the result of impingement of the elongated styloid apparatus upon the various anatomical structures of the head and neck. Although the pathogenesis of the syndrome is still unknown, the impinging theory can provide explanations for the variety of symptoms. A fracture of the styloid process and the associated granulation tissue can result in pressure on surrounding structures. Direct pressure upon the glossopharyngeal, the lower branch of the trigeminal and the chorda tympani nerve can produce symptoms accordingly. The impingement of the carotid vessels and the irritation of the sympathetic nerve plexure in the carotid sheath may lead to neurological symptomatology. The direct irritation of the pharyngeal mucosa is responsible for the dysphagia and pharygodynia. Finally insertion tendonitis due to degenerative and inflammatory changes at the tendinous insertion is a well established cause of pain. According to the literature 4% of the population is estimated to have an elongated styloid process but only a small percentage will demonstrate symptoms. Physical examination can reveal the ossified styloid apparatus on palpation. Plain radiographs can suggest the syndrome but MDCT with its multiplanar capability is the modality of choice for establishing the correct diagnosis. Treatment of the syndrome is either conservative or surgical. Non operative management is based on oral NSAIDS and local steroid-analgesic injections. Surgery is carried out either through a transpharyngeal or an extraoral approach. In our case, MDCT depicted the syndrome and in addition demonstrated the close association of the elongated styloid apparatus with the carotid vessels. This finding might explain the patient’s neurological picture since no severe degenerative findings and disk herniations were depicted from the cervical spine. A CT angiogram, that could verify our theory, was not performed because of a reported severe allergy to contrast media. Finally, bilateral fractures of the styloid apparatus with associated pseudarthrosis are a rare underreported entity that could explain the patient’s pain syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Bilateral ossification of the stylohyoid ligament: the Eagle syndrome

Liscense

Figures

MDCT

MPR Coronal plane

MIP image

VRT image

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Radiological Findings

Based on the patient's cervical CT images, the following can be observed:

1. Bilaterally elongated (or partially calcified) styloid-stylohyoid ligament structures, appearing as “cord-like” images near the level of the hyoid bone, palpable on examination and visible on imaging.

2. Possible areas of fracture and pseudoarthrosis (false joint) formation in portions of the styloid process or ligament.

3. In coronal views, the elongated or calcified styloid-stylohyoid ligament is in close proximity to major cervical vessels (the internal carotid artery), potentially compressing or irritating relevant neurovascular structures.

4. No significant severe degeneration or herniation is observed in the cervical vertebrae and intervertebral discs. The mild degenerative changes present are not sufficient to fully explain the patient’s bilateral upper limb weakness and numbness.

II. Potential Diagnoses

- Eagle Syndrome (Elongated Styloid Process Syndrome): Suggested by the elongated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament. Typical symptoms include pharyngeal discomfort, neck pain, difficulty swallowing, and possible neurovascular compression symptoms, consistent with this patient’s presentation.

- Soft Tissue or Other Neck Space-Occupying Lesion: Abnormal growths that compress cervical vessels or nerves could produce similar symptoms. However, imaging only indicates abnormalities of the styloid process and ligament, with no obvious tumor-like or acute lesions, making this less likely.

- Cervical Degenerative Changes Leading to Nerve Root or Spinal Cord Compression: Cervical CT indicates limited degeneration, and the primary symptoms and involvement are more consistent with styloid or ligamentous compression, thus this remains only a differential consideration.

III. Final Diagnosis

Taking into account the patient’s clinical presentation (neck pain, bilateral upper limb weakness and numbness, palpable “cord-like” structures at the level of the hyoid bone) combined with the CT findings (bilaterally elongated styloid-stylohyoid ligaments adjacent to the internal carotid artery, with possible partial fracture and pseudoarthrosis), the most likely diagnosis is: Bilateral Eagle Syndrome (Elongated Styloid Process), with possible ligamentous disruption and pseudoarthrosis formation.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

1. Conservative Treatment: For patients with mild symptoms or those unable to undergo surgery, oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and local steroid-anesthetic injections can be considered for pain relief. Physical therapy such as cervical physiotherapy and heat applications may help reduce pain and muscle tension.

2. Surgical Treatment: For patients whose symptoms persist despite conservative management, significantly affecting their quality of life, or who have notable neurovascular compression risk, surgical intervention may be considered. Approaches include transcervical or transoral resection of the elongated styloid process or calcified ligament to achieve decompression. The choice of surgical approach depends on the surgeon’s evaluation and the patient’s preference.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription:

- Early Stage (Preoperative or Conservative Phase): Under the premise of avoiding severe pain, daily gentle cervical exercises can be performed, such as low-intensity isometric neck muscle contractions held for 5–10 seconds, repeated 5–8 times, 2–3 sets per day. Avoid excessive rotation or hyperflexion/extension.

- Postoperative (Early Phase): After wound healing, under the supervision of a rehabilitation therapist, gradual neck stretching and stabilization training are recommended, including gentle flexion/extension and lateral flexion against slight resistance, performed 3 times per week, at light-to-moderate intensity, for about 15–20 minutes per session.

- Later Stage (Functional Reconstruction): Progressively increase neck and shoulder muscle strengthening exercises, such as using resistance bands or small dumbbells to train deep neck flexors and scapular stabilizers. Exercise 3–4 times per week at moderate intensity for 20–30 minutes each session. Progression should be based on tolerance and therapist assessments.

- Safety Precautions: In cases of osteoporosis or compromised cardiopulmonary function, reduce resistance and extend rest intervals. Monitor for pain or discomfort during exercise, and adjust the program accordingly. Always follow medical advice for rehabilitation training.

V. Disclaimer

This report provides a reference analysis based on the imaging findings and current clinical information and does not replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. If symptoms worsen or you have further concerns, please consult an appropriate specialist or return for follow-up.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Bilateral ossification of the stylohyoid ligament: the Eagle syndrome