A patient with haemophilic haemarthrosis and arthropathy

Clinical History

A 13-year-old boy came to the emergency department with swelling and marked local inflammation of the right knee lasting for one week.

His father referred a history of haemophilia with recurrent episodes of right knee swelling and also a previous surgery (1 year ago).

Imaging Findings

Initially plain films of the knee were obtained. These showed widening and erosion of intercondylar notch, enlargement of distal femoral epiphysis and flattening of distal femoral condyles. There was also an irregularity of the articular surfaces and subchondral sclerosis. Peri-articular density was present in such an extent that a huge soft tissue mass resulted (“haemophiliac pseudotumour”).

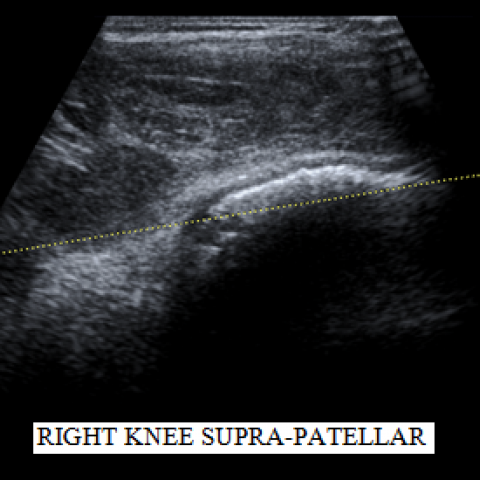

The patient then had a knee Ultrasonography to evaluate the intra-articular contents and ecogenicity of the soft tissue mass. It revealed a mixed echogenicity content in the medial and lateral recesses of the knee and in the subquadricipital recess. There was also significant Doppler signal. These findings were related to haematoma and inflammatory activity. There was also oedema of the subcutaneous tissues.

A MR study was performed one week later. It showed heterogeneous signal intra-articular content, multiple bone erosions and an osteochondral lesion in the medial condyle.

Discussion

This 13-year-old boy had swelling and marked local inflammation of the right knee lasting for one week. His clinical history included a previous right knee sinovectomy and Haemophilia A.

Haemophilia A results from a lack of clotting factor VIII. It is a sex-linked disease, making women asymptomatic carriers [1].

The most typical manifestation of haemophilia is haemarthrosis [2]. When haemarthrosis becomes frequent and/or intense, the synovium may not be able to reabsorb the blood. To compensate for such reabsorptive deficiency, the synovium will hypertrophy, resulting in what is called chronic haemophilic synovitis (in approximately one half of the patients) [3]. The synovitis, along with the ferritine deposition in the hyaline cartlilage leads to sloughing of the cartilage and thus secondary osteoarthritis. Patients develop chronic deformities in one or more joints, which clinically and roentgenographically resemble rheumatoid arthritis [4]. There is marked synovial membrane hyperplasia, destruction of articular cartilage, and erosions of subchondral bone [3].

An abnormally increased vascularity around the epiphysis can occur in certain inflammatory conditions, such as chronic haemophilic synovitis. This can cause growth disturbance with a premature elongation of the bone [2]. Overgrowth of the femoral condyles leads to widening of the intercondylar notch, and overgrowth of the patella causes the appearance of squaring of its inferior pole [3].

Further, as patients age, the recurrent bouts of inflammation ultimately lead to premature closure of the patient’s physeal plates around the affected joint. This means that, once the patient reaches adulthood, an affected leg may be shorter than an unaffected leg. If the epiphyses close unevenly, the joints may also develop deformities [2].

Thus, it is very important not only to avoid acute haemarthrosis, but also to manage it as efficiently as possible, in order to avoid the development of synovitis [4].

Haematological prophylactic treatment from the age of two to the end of skeletal maturity is the best way to avoid articular bleeds, or at least to diminish their intensity [4]. In cases of well established arthropathy, sinovectomy is often necessary to stop rapidly advancing osteoarthritis [5].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Haemophilic arthropathy and hemarthrosis

Liscense

Figures

Knees - Frontal X-ray

Knees - Lateral X-ray

Right anterior knee - Longitudinal US

Right anterior knee - Longitudinal Doppler-US

Righ knee - Sagittal T1 weighted image

Righ knee - Coronal Proton Density image

Imaging Findings

According to the provided X-ray anteroposterior and lateral views, the right knee joint space is irregular. The femoral condyle and tibial plateau show certain bony changes, with irregular sclerosis at the articular margins and potential signs of bone erosion. The femoral condyle appears widened, and the intercondylar notch is enlarged, suggesting possible overgrowth.

Ultrasound reveals significantly thickened synovium in the suprapatellar bursa region, with increased color Doppler blood flow signals, indicating synovial proliferation and active vascular supply.

MRI further confirms destruction and thinning of the articular cartilage surfaces, marked synovial proliferation, joint effusion, and synovial thickening. Surrounding soft tissues also exhibit varying degrees of inflammatory changes. Overall, these imaging findings are highly consistent with recurrent joint bleeding, synovial hyperplasia, and secondary osteochondral destruction.

Potential Diagnoses

-

Chronic Hemophilic Arthropathy (Hemophilic Synovitis)

Given the patient's known Hemophilia A and multiple episodes of joint bleeding, the imaging findings—typical synovial hypertrophy, erosive changes, and cartilage damage—support chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Repeated hemorrhages lead to iron deposition within the joint and chronic inflammatory changes, which align with this case’s progression. -

Infectious Arthritis

Acute joint swelling and pain prompt consideration of infection. However, the patient’s history, chronic course, and the characteristic hemophilic joint changes on X-ray and MRI are more suggestive of a hemophilia-related pathology. Lab tests, body temperature, and other parameters should still be checked to exclude acute infection. -

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

While chronic synovitis may be present, it often has immunologic or other clinical features (e.g., polyarticular involvement, systemic symptoms). Although hemophilia-related joint damage can appear erosive on imaging, the patient’s established history of hemophilia points toward hemophilic arthropathy.

Final Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s age, history of Hemophilia A, recurrent joint bleeds, previous synovectomy, and the imaging findings (marked right knee synovial proliferation, cartilage destruction, bone erosion, and a tendency toward joint deformity), the most likely diagnosis is “Chronic Hemophilic Arthropathy (Hemophilic Synovitis with Secondary Osteochondral Changes).”

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

1. Medications and Conservative Management:

- Coagulation Factor Replacement Therapy: For Hemophilia A patients, standard replacement of factor VIII under specialized supervision is recommended to prevent or reduce further joint bleeding.

- Anti-inflammatory and Analgesic Medications: Short-term use of NSAIDs under a physician’s guidance can alleviate joint pain and inflammation, but bleeding risks must be considered.

- Braces or Knee Support: Use of knee braces may help reduce excessive stress on the joint during activities, when necessary.

2. Surgical Indications and Options:

- For pronounced synovial proliferation with secondary articular cartilage destruction where recurrent bleeding cannot be controlled conservatively, repeat synovectomy or arthroscopic debridement may be considered to reduce synovial inflammation and the frequency of bleeding.

- In cases of severe joint destruction or significant deformity, joint reconstruction or joint replacement may be required, contingent upon adequate coagulation factor replacement and expert evaluation.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription:

(Following the FITT-VP principle: Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Progression, and Monitoring)

- Initial Phase: Recommended 3 times per week of low-intensity exercises, such as walking in water or gentle knee flexion-extension in a seated position, lasting about 15–20 minutes per session. The intensity should avoid causing significant joint pain or discomfort.

- Intermediate Phase: Once symptoms improve and the patient adapts to the initial phase, increase to 4 sessions per week, with each session lasting 20–30 minutes. Introduce resistance band exercises to strengthen the quadriceps and hamstring muscles for better joint stability.

- Later Phase: If joint function improves further, increase to 5 sessions per week, with at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity training per session. This can include stationary cycling or light squats (below the pain threshold). Gradually increase training intensity under well-controlled bleeding risks.

- Important Note: Owing to the tendency for hemophilic joints to bleed, monitor for swelling, pain, or other symptoms after each exercise session. Should any abnormalities arise, suspend exercise and seek medical advice. Factor replacement before rehabilitation sessions may be warranted under professional guidance to ensure safety.

4. Daily Care and Follow-Up:

- Regularly monitor coagulation parameters and joint status, adjusting the dose of factor replacement as needed.

- Avoid high-impact activities or sports with increased risks of falls or trauma; maintain a healthy weight to lessen joint stress.

- Provide education for adolescents and families on proper joint protection and self-monitoring strategies.

Disclaimer: This report is based on available information and is for reference only. It should not replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. If any doubts arise or symptoms worsen, please seek medical attention promptly and follow the guidance of a specialist.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Haemophilic arthropathy and hemarthrosis