Jefferson fracture

Clinical History

A 46-year-old female patient without any significant medical history was admitted to the emergency room after having fallen from a horse. She described an axial impact on her head, without loss of consciousness, and complained about acute neck pain. She was haemodynamically stable, and her neurological status was unremarkable.

Imaging Findings

Plain radiographs of the cervical column were obtained (Fig. 1a-c), showing two fracture lines of the posterior arch of the atlas. There was no atlanto-occipital or atlanto-axial dislocation, and no evident vertebral fracture on a more caudal level.

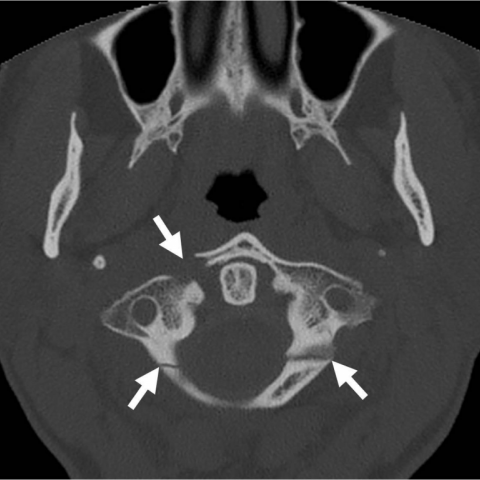

A computed tomography (CT) examination of the head and the cervical spine was then performed (Fig. 2), showing an additional fracture line of the anterior arch of the atlas on the right with a 4 mm diastasis between the main fragments. No skull fracture or intracranial bleed was present.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was finally realized, confirming integrity of the transverse ligament of the atlas (Fig. 3).

Discussion

First described in 1920, Jefferson fracture is a rare fracture of the atlas, defined by concomitant fractures of its anterior and posterior arches, leading to a burst of the atlas ring. It generally results from axial loading upon the cervical spine, similar to occipital Anderson fracture. Different variants of Jefferson fractures have been described depending on the number of fracture lines, ranging from two to four, the latter being the most common variant [1].

Patients have a history of head or neck trauma and present with neck pain.

In general, no neurological deficits exist as the fracture entails a burst of the atlas ring and tends to enlarge the spinal canal. If present, neurological symptoms are mostly attributable to other associated cervical spine lesions, as it is the case in up to 50% of C1 fractures, and not less than 43% of them are associated with C2 fractures [1, 2].

Three-view conventional radiographs are commonly performed initially. Three main signs of a Jefferson fracture that should be remembered are: firstly, on the lateral view, an abnormal width of the retro-pharyngeal soft-tissue shadow; secondly, on the same incidence, a predental space exceeding 4 mm; thirdly, on the open-mouth view, a displacement of the lateral masses of C1 (offset), traducing the burst of the arch [2]. It has been experimentally demonstrated that, when exceeding 6.9 mm, the sum of the displacement of the two lateral masses of C1 over the upper articular surfaces of the axis is highly suspect of a disruption of the transverse atlantal ligament [3]. CT is the best technique to assess cervico-occipital junction lesions, including Jefferson fractures. Axial views may show avulsion of a tubercle on the medial surface of a lateral mass of the atlas, corresponding to the insertion site of the transverse ligament [1], indicating instability of the atlantoaxial complex even in non-displaced fractures.

Magnetic resonance imaging is irreplaceable in soft tissue analysis. It is generally performed to confirm or rule out ligamentous injury, or lesions of the spinal cord.

Non-displaced and stable Jefferson fractures are treated conservatively by hard collar immobilisation. Unstable fractures on the other hand require a more aggressive treatment including axial distraction, halo vest immobilisation, or posterior or trans-oral C1-C2 internal fixation.

In summary, Jefferson fracture is a burst-like fracture of the atlas that, if isolated, does normally not cause neurological deficits. Complete imaging workup is indispensable to search for signs of instability and other associated vertebral lesions.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Jefferson fracture

Liscense

Figures

Admission cervical radiographs

Subsequent CT

MRI

Radiological Analysis Report

I. Radiological Findings

Based on the provided X-ray (AP, lateral, and open-mouth), CT, and MRI images, the following key points are noted:

- Disruption of the cortical continuity of the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas (C1): On the open-mouth X-ray, the outer margin of the C1 lateral mass is significantly displaced relative to the C2 lateral mass (also referred to as “offset”), indicating a “burst-like” fracture of the atlas.

- Widened predental space: On the lateral view, the predental space width exceeds 4 mm, suggesting potential atlantoaxial instability.

- Enlarged soft tissue shadow near the uncovertebral joint: On the lateral view, thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissue is apparent, which could be indicative of acute injury or hemorrhage.

- CT axial view: Shows multiple fracture lines involving the anterior arch, posterior arch, or lateral masses of C1. Fracture lines are seen locally, and in some cases, avulsion at the transverse ligament attachment is noted.

- MRI sequences: Demonstrate regional soft tissue swelling, highlighting the need to assess the integrity of ligaments around the atlantoaxial joint (especially the transverse ligament). High signal changes may suggest ligamentous injury.

II. Differential Diagnosis

Considering the clinical history (axial force transmission from a fall from a horse) and the radiological findings, the following diagnoses or differential diagnoses are proposed:

- Jefferson fracture (C1 burst fracture): The most likely diagnosis, characterized by fractures of the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas accompanied by lateral mass separation, often seen with axial loading or falls.

- Isolated C1 anterior/posterior arch fracture: If only one arch segment is fractured with minimal displacement, it should be distinguished from the full Jefferson fracture.

- Odontoid fracture: A concomitant fracture of the odontoid process (C2) may occur in high-impact falls, so a thorough CT examination is required to rule this out.

- Other burst or compression fractures in the lower cervical spine: Carefully evaluate other segments (C3–C7) for additional combined fractures.

III. Final Diagnosis

Combining the patient’s age (46 years), mechanism of injury (fall from a horse causing axial loading), clinical presentation (acute neck pain without obvious neurological deficits), and radiologic findings (fractures of the C1 anterior and posterior arches, significant lateral mass displacement, increased predental space), the most likely final diagnosis is:

- Jefferson fracture (C1 burst fracture)

If doubt persists or if there is clinical suspicion of ligamentous injury (especially transverse ligament avulsion), further evaluation with MRI or dynamic radiographs is recommended to assess atlantoaxial stability.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Protocol

Treatment strategy depends on the degree of fracture displacement and the stability of the atlantoaxial joint. In this case, if the fracture is deemed stable (minimal displacement and intact transverse ligament), conservative management may be considered; however, significant displacement or ligamentous disruption typically warrants surgical intervention.

- Conservative Treatment:

- For stable fractures, a cervical collar or rigid orthosis (e.g., a hard collar) can be used for about 6–12 weeks.

- Periodic follow-up with X-ray or CT is essential to monitor fracture healing during immobilization.

- Surgical Treatment:

- For unstable fractures (with transverse ligament injury, marked displacement, or other upper cervical structural damage), posterior or transoral surgical fixation may be indicated. A halo vest device may be necessary for additional stabilization.

- Postoperative care emphasizes maintaining proper cervical alignment and stability, with regular follow-up to assess fracture healing.

Rehabilitation/Exercise Prescription Recommendations (FITT-VP Principle)

- Early Phase (0–6 weeks):

- Mainly focus on immobilization with a brace and limiting excessive cervical motion.

- Under medical supervision, isometric neck exercises (e.g., mild resistance for flexion, extension, and lateral bending) can be practiced once or twice daily, for about 5–10 minutes each session.

- Simple resistance or endurance exercises for the lower limbs and trunk can be done to maintain overall fitness.

- Mid Phase (6–12 weeks):

- If the fracture shows good healing, gradually reduce brace usage and start increasing the range of motion (ROM) for the neck.

- Low-intensity aerobic exercise (e.g., walking or using a stationary bike) under professional guidance is encouraged 3–5 times a week, 20–30 minutes per session, at 40–60% of the maximum heart rate.

- Neck muscle exercises can be intensified slightly in terms of ROM and mild resistance, performed daily 1–2 times, for 10–15 minutes per session.

- Late Phase (after 12 weeks):

- Upon confirming good fracture healing clinically and radiographically, normal daily activities can be resumed alongside progressively advanced strength and stability training.

- Gradually increase aerobic exercise to 30–45 minutes per session, with intensity raised to 60–70% of the maximum heart rate.

- Incorporate cervical core stability exercises (e.g., pain-free variations of plank exercises, resistance band training) with progressive increments in repetitions and load.

Throughout the rehabilitation process, closely monitor neck pain and functional changes. If any discomfort or neurological symptoms (e.g., increased pain, numbness, or weakness) occur, seek medical attention immediately.

Disclaimer: This report is intended for reference only and cannot replace face-to-face consultation or a professional physician’s final judgment. If you have any concerns or if symptoms worsen, please seek medical attention promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Jefferson fracture