Axillary nerve entrapment by paralabral cyst

Clinical History

A 76-year-old male with no relevant history of trauma presented with progressive onset shoulder pain and loss of strength in the right arm. Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) of the right shoulder was performed to evaluate rotator cuff tendinopathy.

Imaging Findings

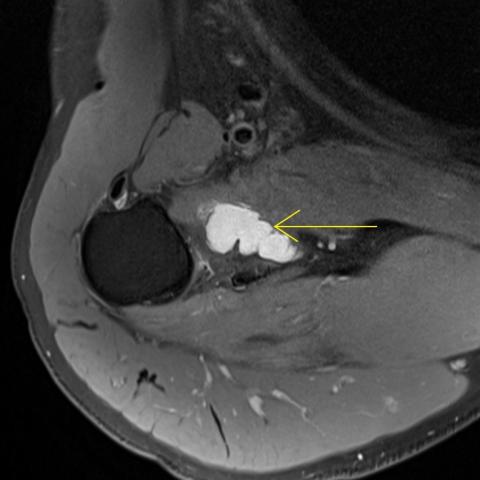

Fat-suppressed proton-density and T1-weighted MR images of the right shoulder demonstrate an extensive tear in the anteroinferior labrum, with a large, lobulated, paralabral cyst (yellow arrows) originating at 5 o'clock, moulded to the anteroinferior margin of the glenoid, between the glenoid and the inferior edge of the subscapularis muscle. There are no other lesions occupying the quadrilateral space, although the volume of the paralabral cyst results in an increase in volume of the subscapularis muscle and external impingement on the quadrilateral space and traversing axillary nerve (blue arrows). There is no effusion in the glenohumeral joint. The teres minor tendon is normal, with moderate atrophy and fatty infiltration of the teres minor muscle (red arrows), consistent with isolated denervation of this muscle in chronic quadrilateral space syndrome. There were no changes to the deltoid muscle.

Discussion

The axillary nerve supplies the shoulder with both motor and sensory branches. It is one of the two terminal branches arising from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, with inputs from the C5 and C6 nerve roots. The axillary nerve crosses the axilla through the quadrilateral space, along with the posterior humeral circumflex artery and vein. The quadrilateral space is defined superiorly by the teres minor muscle, inferiorly by the teres major muscle, medially by the long head of the triceps and laterally by the humerus [1]. The axillary nerve gives rise to three branches: the anterior branch, supplying the anterior portion of the deltoid; the posterior branch, supplying the teres minor and posterior deltoid; and the articular branch, supplying the anteroinferior glenohumeral joint [1]. The posterior branch of the axillary nerve then continues as the upper lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm, innervating the skin over the lateral deltoid [1].

The quadrilateral space is the most common site of axillary nerve entrapment, which can result from extrinsic compression by large osteophytes of the glenohumeral joint, paralabral cysts, most commonly originating on the posteroinferior aspect of the labrum, tumours, anterior shoulder dislocations and scapular fractures [2].

Clinically, quadrilateral space syndrome frequently presents with posterior shoulder pain, paraesthesia over the lateral aspect of the deltoid, weakness of the deltoid and teres minor muscles, and even paleness and cyanosis of the distal upper limb, if the posterior humeral circumflex artery is also affected [3].

Although MR imaging is the modality of choice when evaluating the quadrilateral space for potential space-occupying lesions causing axillary nerve entrapment, ultrasound may be useful in identifying signs of chronic denervation of the teres minor or deltoid muscles, with increased muscle echogenicity and atrophy [4]. Point tenderness over the quadrilateral space is also suggestive of axillary nerve entrapment [2]. MR imaging of the axillary nerve may reveal flattening of the nerve at the site of entrapment, with proximal enlargement and increased T2 signal [5,6]. Denervation oedema may be found acutely, and muscular atrophy with adipose infiltration in chronic denervation [7]. MRI arthrography can demonstrate communication between a labral tear and paralabral cyst [8].

Treatment of paralabral cysts includes surgical repair of the associated labral tear, with or without drainage of the cyst [9,10]. In our case, the patient was not a good candidate for rotator cuff surgery and conservative treatment was elected.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Axillary nerve entrapment and teres minor atrophy by paralabral cyst

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Imaging Findings

1. A cystic lesion with clear boundaries and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images is observed near the quadrilateral space region at the posterior aspect of the shoulder joint (indicated by the yellow arrow). Its shape and characteristics suggest fluid density or a cystic lesion.

2. The lesion is located in the area behind the glenoid, near the humeral head and the labrum, showing a multi-lobular or septated bright white signal, consistent with the common imaging features of a "paralabral cyst."

3. The adjacent deltoid and teres minor muscles exhibit mild local morphological changes, with possible slight atrophy or fatty infiltration in some areas, suggesting chronic nerve compression-induced muscular changes.

4. No obvious fracture signals or significant bony destruction are seen, and the articular surfaces remain largely intact. Mild osteophyte formation is noted around the acromion or glenohumeral joint.

II. Potential Diagnoses

Based on the above imaging findings and the patient’s clinical symptoms of shoulder pain and decreased strength, possible diagnoses or differential diagnoses include:

1. Quadrilateral Space Syndrome: Caused by a paralabral cyst or other space-occupying lesion compressing the axillary nerve and accompanying vessels, potentially presenting with sensory abnormalities over the lateral aspect of the shoulder and weakness or atrophy of the deltoid and teres minor muscles.

2. Paralabral Cyst with Labral Tear: If there is a tear of the glenoid labrum (especially the posterior inferior labrum), a cyst may form and subsequently compress the nerve.

3. Other Nerve Compression or Tendon Pathologies: For example, large osteophytes, tumors, or residual lesions from old shoulder injuries. However, given no significant history of trauma or findings suggestive of malignancy, these are considered less likely.

III. Final Diagnosis

Taking into consideration the patient's age (76 years), progressive shoulder pain and decreased strength, absence of a clear trauma history, and the imaging presentation of a cystic lesion in the quadrilateral space area with mild muscle atrophy, the most likely diagnosis is: Quadrilateral Space Syndrome caused by a paralabral cyst compressing the axillary nerve.

If more precise evaluation of labral tears is needed, arthroscopy or further arthrographic examination can be considered. However, given the patient’s general condition, conservative treatment remains the primary approach.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Schedule

1. Treatment Strategies:

- Conservative Treatment: Includes oral or local injection of anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications, and therapies promoting blood circulation to relieve symptoms. If symptoms are severe and the cyst is large, image-guided aspiration and decompression may be considered, though procedural risks should be noted. Patient’s symptoms and muscle strength recovery should be monitored.

- Surgical Treatment: In cases with a conspicuous labral tear, severe symptoms, recurrent issues, or failure of conservative management, arthroscopic repair of the labrum and removal or drainage of the cyst can be considered. Nevertheless, for this older patient who is not an ideal surgical candidate, surgery is not currently a priority.

2. Rehabilitation/Exercise Prescription (FITT-VP Principle):

- Frequency (F): 3-4 times per week, adjustable based on patient tolerance and symptom relief.

- Intensity (I): Low to moderate intensity, avoiding excessive stretching or vigorous activities that might cause further injury. If pain is significant, begin with passive or assisted exercises.

- Time (T): 10-30 minutes each session. Can be divided into shorter sessions, gradually lengthening as rehabilitation progresses.

- Type (T):

① Range of Motion Exercises: Such as pendulum exercises, passive abduction, and adduction to maintain shoulder joint flexibility.

② Shoulder Girdle Strengthening: Start with isometric contractions or low-resistance band exercises and gradually increase resistance to strengthen the deltoid and rotator cuff.

③ Proprioception Training: Incorporate mild functional exercises (e.g., extension, scapular exercises) to improve balance and joint position sense.

- Volume & Progression (V & P): Initially focus on protection and recovery. As pain subsides and muscle strength improves, progressively increase the range of motion and resistance, while closely monitoring the shoulder’s response. If significant pain or other discomfort occurs, promptly evaluate and adjust the exercise plan.

- Note: As this patient is older with potentially reduced bone density and possibly limited cardiopulmonary function, safety during exercises must be ensured, and exercises should be within a tolerable range. Professional guidance from a rehabilitation specialist or therapist is recommended if necessary.

Disclaimer: This report is a reference based on the provided information and should not replace an in-person consultation or professional medical advice. If you have any concerns or changes in your condition, please seek medical attention promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Axillary nerve entrapment and teres minor atrophy by paralabral cyst