An eleven-year follow-up of a growing osteochondroma of the fibula causing tibiofibular synostosis

Clinical History

The patient presented with a lump and vague pain in the posterolateral aspect of her proximal calf. The lump had been growing in the region for 11 years. Physical examination revealed a hard and tender mass in the lateral aspect of the right upper calf. Routine laboratory studies were normal.

Imaging Findings

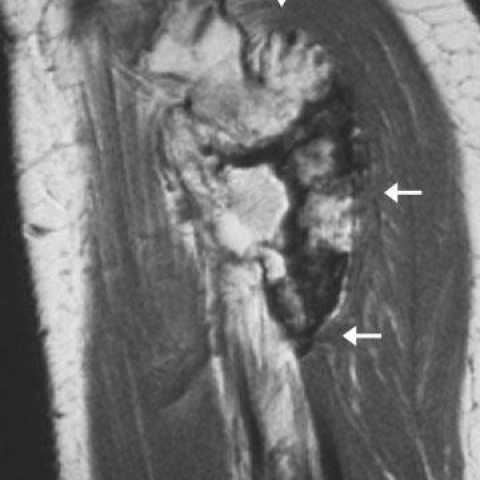

Plain radiographs of the involved calf showed a large osseous excrescence arising from the external surface of the upper fibula and containing spongiosa and cortex that were continuous with those of the parent bone (Fig. 1). The bony outgrowth was sessile with a broad, flat base. On MR images, a solitary osteocartilaginous exostosis was seen (Figs. 2-4). There was continuity of the cortical and medullary bone in the lesion with that of the parent bone, a finding merely diagnostic of an osteochondroma. The cap of the osseous protuberance displayed the imaging characteristics of cartilage, showing high signal intensity on T2-weighted spin echo MR images. Due to the large size of the osteochondroma, tibiofibular synostosis (bony bridge) was produced with pressure deformity in the nearby tibia. There was bowing of the fibula, and minimal diastasis of the proximal tibiofibular joint.

Discussion

Osteochondroma, also known as osteocartilaginous exostosis, is the most common benign bone tumour, representing 10-15% of all primary bone tumours and up to 50% of benign tumours [1]. Osteochondroma may develop after irradiation or may arise spontaneously. Lesions are composed of cortical and medullary bone with an overlying cartilage cap. The radiologic hallmark of osteochondroma is continuity of lesion with the marrow and cortex of the underlying parent bone.

Osteochondromas occur most commonly around the knee (40% of cases). The femur is the most-affected bone (30%), while tibial lesions account for 15-20% of cases [2]. Osteochondromas may be solitary or multiple as part of the hereditary multiple exostoses syndrome (HME) [1]. Complications are more common with multiple osteochondromas and include deformity (cosmetic and bone), fracture, vascular injury, neurologic compromise, overlying bursa formation, and malignant transformation. Bone deformity includes osseous bowing, malalignment and extrinsic pressure erosion of adjacent bones. When paired bones of the forearm or lower leg are involved, scalloping of the cortex may ensue.

The size of osteochondromas varies between 1-10 cm. Continued lesion growth after skeletal maturity, and a cartilage cap greater than 1.5 cm suggest malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma [3]. Solitary osteochondromas are usually asymptomatic with a male predilection ranging from 1.6-3.4 to 1. Small asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic lesions should be followed-up, while symptomatic lesions should be resected. Patients with HME require continued clinical and imaging surveillance to evaluate progression of lesions, or complications. Measurement of thickness of a cartilage cap can be accomplished with ultrasound, while CT or MR imaging are best suited for the evaluation of complex anatomic areas [1].

On radiographs, osteochondroma appears as a sessile or pedunculated bone excrescence, containing both spongiosa and cortex that are continuous with those of the parent bone. The cartilaginous cap has a variable degree of calcification.

Typically, osteochondromas tend to point away from the adjacent joint. Widening of the involved metaphysis of tubular bones may be noted. MR imaging often reveals yellow marrow centrally (which has high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images) with a low-signal intensity cortex. The cartilage cap has low to intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images. Mineralized portions in the cartilage cap remain low signal intensity with all MR sequences. After the intravenous administration of contrast, peripheral and septal enhancement in the cartilage cap can be seen.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Osteochondroma of the fibula

Liscense

Figures

Lateral radiograph

Sagittal T1-weighted MR

Axial T1-weighted MR

Coronal T1-weighted MR

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Radiological Findings

1. X-ray (Plain Film) Observations:

- A protruding lesion is seen near the right tibia proximal fibula area, appearing like an “exostosis.” The lesion shows continuity of the bone cortex and marrow cavity.

- The lesion outline is clear, with relatively distinct borders. A partly cartilaginous cap is visible, and local calcification or ossification can be seen.

- The morphology can be either stalk-like or broad-based, consistent with an exostosis (osteochondroma-like) appearance.

2. MRI Findings:

- Inside the lesion, signals continuous with the adjacent bone marrow can be observed. On T1-weighted images, the central area may show high signal intensity similar to yellow marrow, while the peripheral cortex appears as low signal.

- The cartilaginous cap displays conspicuous high signal on T2-weighted images with thickness within the visible range. If there is any calcification within the cartilage, it typically appears as low signal on all sequences.

- On contrast-enhanced scans, enhancement is observed around the periphery of the cartilaginous cap and within fibrous septa.

Overall, imaging features indicate a lesion with continuity of the bone cortex and marrow, a cartilaginous cap, and local calcification. These findings are consistent with a bony exostosis (osteochondroma-like lesion).

II. Potential Diagnoses

- Osteochondroma:

This is the most common benign bone tumor, formed by an outgrowth of bone cortex and marrow. It frequently occurs at the metaphysis of long bones, and imaging demonstrates continuity of the cortex and marrow with the parent bone. If the cartilage cap is thick (e.g., >1.5 cm) or continues to grow in adulthood, malignant transformation should be considered.

- Chondrosarcoma:

Occasionally, osteochondroma can undergo malignant transformation into chondrosarcoma, especially when the cartilaginous cap is significantly thickened or the lesion grows rapidly in adulthood with worsening pain. Typical chondrosarcoma often shows destructive growth with marked bone destruction and soft-tissue calcification (“ring” or “cluster-like” calcification).

- Other benign bone tumors or tumor-like lesions:

These include osteoid osteoma, enchondroma, etc. However, these lesions typically do not present as a prominent outgrowth and often lack direct continuity with the bone cortex and marrow.

III. Final Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s age (53-year-old female), history (11 years of slow growth, recent worsening pain), physical examination (hard mass), and imaging findings (bony outgrowth with continuity of marrow and cortex, a typical cartilaginous cap, and partial calcification), the most likely diagnosis is:

Osteochondroma.

If further examinations or follow-up imaging confirm a markedly thickened cartilage cap (>1.5 cm) or if the lesion exhibits rapid growth within a short period, the possibility of malignant transformation (e.g., chondrosarcoma) should be considered. A biopsy or higher-resolution MRI might be warranted to confirm the diagnosis.

IV. Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan

1. Treatment Strategy:

- Observation and Follow-Up: If the tumor shows no significant enlargement or indications of malignancy, and the patient’s symptoms are mild, regular imaging follow-up and physical examinations can be conducted.

- Surgical Resection: If there is pain, significant local irritation, or malignant potential (e.g., thickened cartilage cap or rapid growth), surgical removal is advised. Complete resection should include the bony outgrowth and cartilaginous cap to reduce the risk of recurrence and malignant change.

2. Rehabilitation/Exercise Prescription:

- Basic Principles: Start gradually, individualized according to the patient’s bone condition (e.g., bone fragility, postoperative wound healing) and cardiopulmonary function.

- F (Frequency): 3-5 times per week is generally suitable. Begin at a lower frequency (e.g., 2-3 times per week) and gradually increase based on fatigue and recovery.

- I (Intensity): Initially choose low-to-moderate intensity exercises (such as walking, light resistance training), monitoring subjective fatigue and pain levels. Post-surgery or in the presence of pain, start with low intensity and progressively move to moderate intensity.

- T (Time): Begin with 15-20 minutes per session, gradually extending to 30 minutes or more, adjusting based on symptoms and fitness.

- T (Type): Low-impact exercises (such as swimming, stationary cycling, elliptical training) and appropriate resistance exercises (using resistance bands or light weights) are recommended, avoiding excessive stress on the tumor site or postoperative area.

- V (Volume): Increase total exercise volume progressively as patient tolerance improves, being careful not to exacerbate pain or excessively increase fatigue.

- P (Progression): Once patients adapt to a certain intensity and duration, gradually increase workload and complexity to improve muscular stability and overall function.

Throughout the rehabilitation and exercise program, closely monitor both local and general pain, swelling, and fatigue levels. If symptoms worsen, seek medical evaluation promptly.

V. Disclaimer

This report is based on the currently available imaging and clinical information and is provided for reference only. It does not replace a face-to-face consultation or the professional diagnosis and treatment advice of a physician. Patients should proceed with further examinations and treatment under the guidance of a specialist.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Osteochondroma of the fibula