Cortical fracture and procurvatum deformity in a Pagetic tibia

Clinical History

A 70-year-old-man with known Paget’s disease of the bone presented after several months of severe localised pain in his upper right shin, significantly exacerbated by weight-bearing, with no history of trauma.

Examination revealed a procurvatum deformity with localised warmth and tenderness 3-4 cm distal to the right tibial tuberosity.

Imaging Findings

Radiographs 1, 2 and 3 display Paget’s disease of the right tibia with a stress fracture at the anterior cortex of the superior tibia. Image 4 confirms bony abnormality and demonstrates an incomplete injury. Image 5 is a planning radiograph while images 6 and 7, taken 18 months post-operatively, show intramedullary nail placement. The pre-existing procurvium has been corrected and complete union has been achieved.

Discussion

Paget’s disease is a focal disorder of new bone remodelling [1]. While prevalence is currently decreasing in the UK, it remains an important cause of pathological fractures and chronic pain in the older population, affecting 1.6% of women and 2.5% of men over the age of 54 [2]. Medical management of chronic symptoms includes antiresorptive therapy, vitamin D and calcium supplementation [3]. While a mainstay of treatment, the use of bisphosphonates has been linked to the development of atypical fractures, including some reports of atypical tibial fractures [4].

In any patient with Paget’s disease who presents with new symptoms it is important to rule out a more sinister cause of pain, such as osteosarcoma, particularly in those over the age of 60 [5]. Osteosarcomas may not become visible until a relatively late stage on plain radiographic films and therefore further imaging modalities such as MRI are advised. This patient was receiving yearly bisphosphonate infusions for his Paget’s disease and as such it appears likely the use of bisphosphonates in combination with the bony deformity predisposed this patient to developing a stress fracture at this site.

Patients with Paget’s disease present unique surgical challenges due to multiplanar deformity requiring careful selection of fixation devices [6]. This patient was extensively counselled about non-operative versus operative intervention. The main risk presented by non-operative management was completion of the stress fracture and subsequent need for operative fixation. This would have presented an extreme surgical challenge.

In this case, fixation was achieved via an opening wedge osteotomy performed posteriorly (hinging on the anterior cortex) in order to maintain maximal muscle cover, followed by insertion of a reamed, locked intramedullary nail. Reaming of the bone was particularly difficult due to the hardness of the bone and loss of the normal intramedullary canal.

The patient’s symptoms resolved in line with the consolidation of the fracture site.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Stress fracture in tibia due to Paget’s disease.

Liscense

Figures

Plain film radiography at presentation

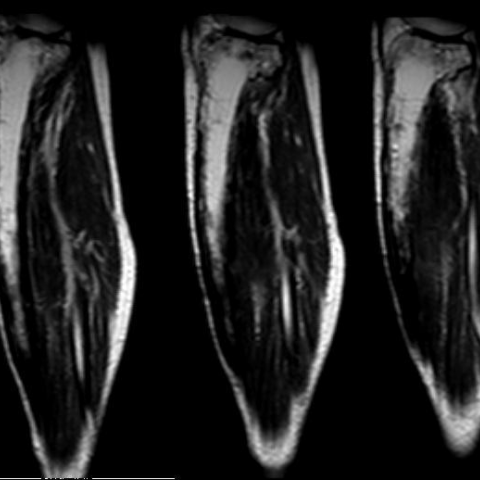

MRI R tibia

Planning image for opening wedge osteotomy.

Intramedullary nail placement and internal fixation at 18 months post op

Preoperative CT

Medical Analysis Report

I. Radiological Findings

According to the provided X-ray, MRI, and CT images, the following findings are observed:

- From the proximal to the mid portion of the right tibia, there is significant cortical thickening and deformity. In particular, a local deformity (anterior convexity/“procurvatum deformity”) is noted approximately 3-4 cm below the tibial tuberosity, consistent with known abnormal bone remodeling in Paget’s disease.

- Local cortical thickening is evident, and both cortical bone and cancellous bone show mixed areas of sclerosis and lucency, typical of Paget’s disease–related bone changes.

- Near the anterior bowing of the tibia, an irregular longitudinal interruption of trabecular bone or fracture line signal is visible, along with localized sclerotic bands, suggesting a possible stress or atypical fracture.

- MRI reveals discontinuity of the local cortical bone and mild surrounding soft tissue edema, but no obvious soft tissue mass or invasive destruction, ruling out most features indicative of malignancy.

- CT 3D reconstruction clearly shows the bowing deformity of the tibia and the fracture (stress fracture) site, as well as disorganized trabecular structures and a narrowed medullary cavity, which are characteristic of Paget’s disease.

II. Possible Diagnoses

-

Pathological Fracture or Stress Fracture Caused by Paget’s Disease

Given that the patient has a confirmed diagnosis of Paget’s disease with pronounced local bone deformity, along with significant pain after prolonged weight-bearing and radiographic evidence of a fracture line, a stress or pathological fracture in the context of Paget’s disease is a key consideration. -

Atypical Fracture (Related to Bisphosphonate Use)

The patient has been on long-term bisphosphonate therapy (annual IV infusions). It is known that, in rare cases, bisphosphonates can lead to atypical fractures, most commonly in the femur. However, there are reports of such fractures occurring in the tibia as well, so this should be included in the differential diagnosis. -

Malignant Transformation (e.g., Osteosarcoma) in Paget’s Disease

Although the risk of malignancy (especially osteosarcoma) is relatively low in Paget’s disease, it is not impossible. Clinical manifestations can include new-onset or worsening pain and a rapid change in morphology. Due to local deformity and increased pain, malignancy should be cautiously ruled out. While MRI does not show typical signs of malignancy, if there is strong clinical suspicion, further follow-up or biopsy may be necessary.

III. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s advanced age, established history of Paget’s disease, bisphosphonate use, and imaging findings (cortical thickening, fracture line at the site of anterior bowing, and no clear sign of malignancy), the most likely diagnosis is:

“Stress fracture on a tibial deformity secondary to Paget’s disease (with the possibility of an atypical fracture related to bisphosphonates not ruled out).”

The specific clinical manifestations (months of progressively worsening pain, marked pain on weight-bearing) and intraoperative findings (sclerosis, narrowed medullary canal) are consistent with a stress fracture superimposed on Paget’s disease. MRI showing no obvious soft tissue mass or invasive destruction also supports a non-tumorous lesion.

If the pain cannot be explained or if there is abnormal progression seen on follow-up imaging, a biopsy should be performed to rule out malignancy.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

1. Treatment Overview

- Conservative Management: For mild stress fractures or cases without significant deformity, initial management can involve protected weight-bearing, casting or bracing, alongside pain control, and supplementation with calcium and vitamin D.

-

Pharmacological Treatment:

- Continue anti-resorptive therapy (bisphosphonates/denosumab) as needed, but monitor closely for fracture risk and symptoms.

- Ensure adequate intake of calcium, vitamin D, and appropriate protein to support fracture healing and maintain bone stability.

- Monitor serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and other lab markers to assess disease activity in Paget’s disease. -

Surgical Intervention: In cases of significant deformity, high risk of nonunion, or possibility of complete fracture, procedures such as osteotomy and internal fixation can be considered.

In this case, because of pronounced anterior bowing and severe pain, a posterior opening osteotomy (retaining the anterior cortical bone as a pivot) and placement of an expanded intramedullary nail with locking features were performed to stabilize the fracture and correct part of the deformity.

2. Rehabilitation / Exercise Prescription

Given the patient’s abnormal bone quality (Paget’s disease) and postoperative status, rehabilitation must be gradual and individualized:

-

Early Stage (0-6 weeks post-op):

- Perform small-range joint movements and basic muscle strengthening exercises that are tolerable (e.g., quadriceps isometric contractions in a seated or supine position).

- Under the guidance of a physician or physiotherapist, use crutches or walkers with partial weight-bearing, gradually transitioning to weight-bearing as tolerated.

-

Intermediate Stage (6-12 weeks post-op):

- Gradually increase the range of motion exercises for the knee (flexion and extension) and ankle (active movements).

- As fracture healing and pain status permit, begin moderate resistance training (light weights or resistance bands) to strengthen the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles.

- If healing is satisfactory, progress to more controlled balance training using parallel bars or support for single-leg stance.

-

Late Stage (3-6 months and beyond post-op):

- Based on imaging evaluations and fracture healing, gradually advance to normal or near-normal weight-bearing activities.

- Include low-impact aerobic activities such as stationary cycling, swimming, or walking in water to safely improve lower limb strength and cardiovascular fitness.

- Once deformity and pain have significantly improved, resume normal daily activities. Light stair climbing or hiking may be introduced later, but high-impact activities (running or jumping) should be avoided to reduce the risk of recurrent stress injury.

When designing the exercise prescription, follow the FITT-VP principles (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Progression), taking into account bone healing and the patient’s cardiopulmonary reserve. A warm-up is recommended before each exercise session. Initially, each session can last 10-15 minutes and gradually increase to over 30 minutes, 3-5 times a week, with adjustments based on pain and warning signs (e.g., redness, swelling, or warmth).

Safety Precautions: Because Paget’s disease and postoperative fixation both challenge bone stability, it is important to avoid any vigorous or rotational movements that could cause injury. If there is a sudden increase in pain, local swelling, or other discomfort, seek medical evaluation promptly.

Disclaimer

This report is a reference-based analysis generated from the existing medical history and radiological data. It does not replace in-person consultations or professional medical advice. Actual treatment plans must be determined by integrating the patient’s specific circumstances and further offline examinations.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Stress fracture in tibia due to Paget’s disease.