Calcific myonecrosis - a \'do not touch\' lesion

Clinical History

A 64-year-old man was admitted after minor trauma to his right lower leg. He was found to have a large palpable swelling in his lower leg along with absent foot pulses. Further questioning revealed previous trauma 40 years ago, resulting in femoral shaft fracture and compartment syndrome of the lower leg.

Imaging Findings

Radiographs revealed a large soft tissue mass in the anterolateral compartment of the right lower leg with peripheral calcification with erosive changes of the adjacent fibula (Fig. 1).

Computed Tomography angiogram (CTA) was performed to assess the lower limb vasculature. This revealed a large soft tissue mass with peripheral calcification and erosion of the lateral cortex of the fibula (Fig. 2). Intralesional areas of high attenuation (Fig. 3) involving the anterolateral compartment with numerous collaterals were noted (Fig. 4). The popliteal artery and run-off vessels were patent.

As the erosive changes of the fibula were not typical of a non-aggressive lesion (smooth scalloping) a Magnetic Resonance (MR) examination was advised to characterise the mass further.

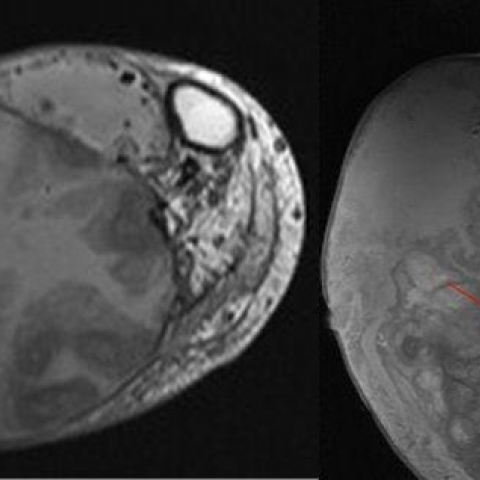

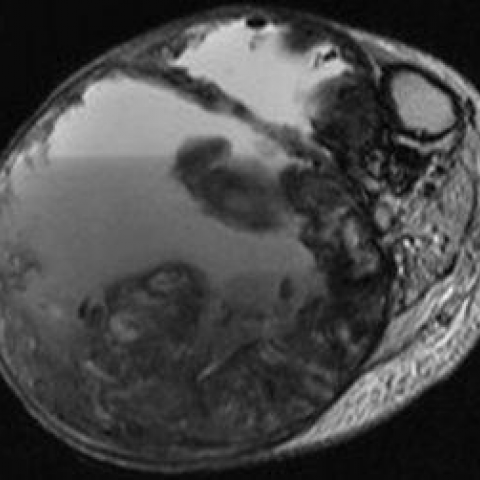

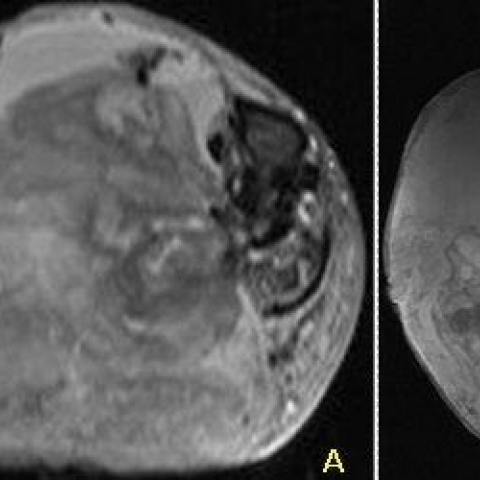

MR demonstrated a non-enhancing mass (Fig. 5) with nodular areas of low T1/T2 signal, cystic/solid components and fluid-fluid levels in keeping with acute and chronic bleeding (Fig 6 and 7). Bone marrow signal was normal.

The diagnosis was made with the combined information of CT & MR. The patient deteriorated due to increased intralesional haemorrhage and sepsis. Subsequently amputation was performed, confirming the diagnosis.

Discussion

Calcific myonecrosis (CM), initially described in 1960 [1], is a rare latent condition as a consequence of compartment syndrome [2], ischaemia and fibrosis [3]. There is usually a history of remote trauma ranging from 10-64 years. The infarct is ellipsoid with its main axis parallel to the long axis of the limb [1]. Repeated intralesional haemorrhage can occur resulting in increasing size of the mass and dystrophic calcification. CM commonly occurs in the anterolateral compartment of the lower leg, but occurrence in the forearm [5, 6] and foot [7, 8] has also been reported. CM usually occurs unilaterally, but two publications report bilateral CM [4, 9].

History of trauma may be difficult to elicit and so radiology is vital in diagnosing CM. Plain radiographs demonstrate a fusiform mass with peripheral plaque/sheet-like calcification. Ultrasound demonstrates irregular or linear echoes with posterior acoustic shadowing [10]. On CT images the fusiform mass has a rim-like calcification with central heterogeneous fluid attenuation, secondary to haemorrhage. There is usually smooth cortical scalloping in keeping with the chronic nature of the lesion, but at times this process can appear destructive mimicking an aggressive process as in our case. Although not necessary, MR can be used to confirm the diagnosis. This can demonstrate thick and nodular or frond-like low signal peripheral rim on T1/T2 weighted sequences, corresponding to the peripheral calcification [11]. The central portion of the mass demonstrates a heterogeneous signal on T1 and T2 weighted sequences as a result of varying age of haemorrhage. Nuclear medicine is non-specific and of limited use [10].

Differentials include malignant lesions such as soft tissue sarcoma (STS), myositis ossificans and posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm. CM can often be distinguished from STSs because of its lack of contrast enhancement and perilesional oedema [2], although there has been one case of enhancing CM [12].

Previously, surgical intervention was advocated, but conservative management is more appropriate as there is high risk of complications, including conversion of sterile necrotic tissue into an abscess, excessive bleeding or fistula formation [3]. It was emphasised not to perform biopsy as this may lead to devastating haemorrhage. Intervention should be considered only when necessary, e.g. in patients with uncontrolled pain. History of trauma may not be elicited, however, classical radiological features should help avoid unnecessary tests and misdiagnosis.

In conclusion, radiology is crucial to the diagnosis of CM preventing a potentially dangerous biopsy or unnecessary intervention. Hence, CM has been classed as a “do not touch lesion”.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Calcific myonecrosis

Liscense

Figures

Plain radiograph of the right lower leg

Axial post contrast CT of the lower leg

CT 3D reconstructions

3D CT angiogram reconstruction

MRI lower leg

MRI lower leg

MRI lower leg

MRI lower leg

1. Imaging Findings

Based on the provided X-ray, CT, and MRI data, an elliptical or spindle-shaped soft tissue mass is observed in the patient’s right lower leg. The main features are as follows:

1. X-ray: Shows fusiform soft tissue swelling, with patchy or lamellar calcifications around the lesion and local calcified deposits within the soft tissue. Slight cortical indentation or “erosion-like” changes can be seen in the adjacent bone.

2. CT: On axial images, a spindle-shaped soft tissue density is visible, with prominent strip-like or shell-like calcifications at the periphery. The central portion has heterogeneous density (possibly reflecting fluid or mixed density) indicating chronic hemorrhage or fibrous components. There is smooth cortical compression of the adjacent bone, but no extensive bone destruction.

3. MRI: The soft tissue mass shows heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, with mixed high and low signals in the center, suggesting varying degrees of chronic hemorrhage and necrotic/fibrotic areas. The peripheral capsule corresponds to a low signal band, consistent with calcific deposits. No obvious enhancement characteristic of a soft tissue tumor is observed.

These imaging findings, in conjunction with the patient’s history of trauma, suggest a chronic, relatively stable lesion with calcification and hemorrhagic components.

2. Potential Diagnoses

The differential diagnoses may include the following:

1. Calcific Myonecrosis (CM): Commonly seen as a late complication following severe crush injury or compartment syndrome. Imaging typically shows a fusiform mass with shell-like calcifications, and the center may exhibit mixed density or signal areas of hemorrhage.

2. Soft Tissue Sarcoma (STS): May present as a soft tissue mass with or without calcification. However, these often show prominent enhancement and invasive features, frequently accompanied by peripheral soft tissue edema.

3. Myositis Ossificans: Usually occurs after trauma and shows a pattern of zonal or band-like calcification, progressing from the periphery inward. This does not fully match the chronic and liquefied necrotic features observed in this case.

4. Post-traumatic Pseudoaneurysm: Can manifest with swelling and calcification (due to calcification of the aneurysm wall). However, on CT or MRI, there is typically a connection to the arterial system and clear contrast enhancement within the lumen.

Considering the patient’s 40-year-old trauma history and the morphological and radiological features, the findings most likely represent the late-stage manifestation of calcific myonecrosis.

3. Final Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s history of trauma and compartment syndrome, along with current imaging findings of a fusiform mass and typical peripheral calcification, and excluding evidence of malignancy or vascular lesions, the most probable diagnosis is “Calcific Myonecrosis.”

4. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

1. Treatment Strategies:

• Conservative Management: If the patient’s pain and functional impairment are not significant, observation and supportive care are generally recommended. Since these lesions are often chronic, stable calcified tissues with no active infectious process, biopsy or surgical intervention may pose risks of secondary infection or significant bleeding. Therefore, a “do not touch” strategy is often advised.

• Surgical Intervention: Surgery may be considered only if the patient experiences persistent pain, marked functional deficit, or if the lesion enlarges rapidly, causing complications. However, surgical resection carries a high risk of bleeding and infection, and should be chosen cautiously after thorough discussion of risks and benefits.

2. Medication and Other Support:

• For pain control, analgesics (such as NSAIDs) may be used to alleviate inflammatory exudation or soft tissue swelling.

• If there is significant vascular compression leading to distal ischemia in the lower limb, further vascular surgery evaluation is necessary to determine whether revascularization or bypass is warranted.

3. Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription:

(1) Principles of Rehabilitation:

• Design an individualized training program based on the patient’s lower limb strength, pain level, and cardiopulmonary function.

• Emphasize maintaining and gradually improving limb mobility while avoiding excessive load that could cause further tissue damage.

(2) Exercise Prescription Recommendations (FITT-VP Principle):

• Frequency: 3–5 sessions per week, adjusted according to the patient’s tolerance.

• Intensity: Emphasize low to moderate intensity exercises (e.g., bodyweight exercises or light resistance) and progress gradually depending on lower limb discomfort and pain tolerance.

• Time: Start with 20–30 minutes per session; if well tolerated, gradually increase duration.

• Type: Prefer activities that minimize joint stress, such as level walking, seated lower limb exercises with light resistance, swimming, or aquatic therapy (using buoyancy to reduce lower limb loading).

• Progression: Once pain is manageable and lower limb strength improves, gradually increase exercise volume or intensity, for example by progressively increasing walking speed or adding light weights.

• Volume & Pattern: Consider dividing the total recommended time into smaller segments (e.g., 10 minutes × 2–3 sessions/day) to avoid excessive fatigue.

(3) Safety Precautions:

• Seek medical evaluation if there is marked increase in pain, swelling, or signs of impaired blood supply (such as numbness or changes in skin color).

• Patients with compromised cardiopulmonary function or other chronic conditions should perform exercises under the guidance of a physician or rehabilitation specialist, adjusting according to individual tolerance.

5. Disclaimer

This report provides a reference analysis based on current information and general medical knowledge and cannot replace an in-person consultation or individualized medical advice. If you have any clinical concerns, please consult a specialist or seek further evaluation and treatment in a hospital setting.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Calcific myonecrosis