Abdominal wall desmoid-type fibromatosis

Clinical History

A 31-year-old female patient presented with a painless, slow-growing mass in the right abdominal wall. A palpable fixed and firm tumour in the right middle third of the lateral abdominal wall was noticed. The patient had no history of trauma, surgery or childbearing. Laboratory testing was unremarkable.

Imaging Findings

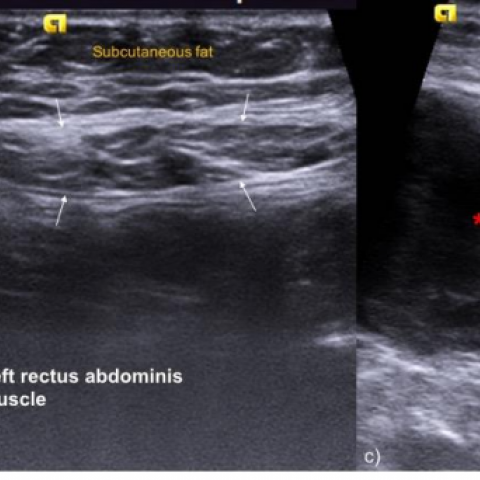

Ultrasound (US) was the method of choice for initial screening, revealing a fairly well-defined, heterogeneous hypoechoic mass localized in the right rectus abdominis muscle (Fig. 1). Detectable flow by Doppler US was considered indeterminate.

Additional evaluation with computed tomography (CT) depicted a well-circumscribed, mild enhancement soft-tissue mass originating from the right rectus abdominis muscle. There was no evidence of calcifications or necrosis within the mass. No signs of invasion of the adjacent intraabdominal organs were found (Fig. 2).

Subsequently, an US-guided core needle biopsy was performed and the results were compatible with desmoid-type fibromatosis.

After preoperative workup, the patient was scheduled for surgery. While waiting for the procedure, a painful augmentation of the mass motivated a reevaluation CT (2 months later) which confirmed an important tumour growth but still without intraabdominal cavity invasion (Fig. 3).

The patient underwent a successfully complete resection of the tumour with negative microscopic margins.

Discussion

Desmoid-type fibromatosis (DF), also known as aggressive fibromatosis, is a locally aggressive tumour, with no potential for metastasis [1]. This fibroblastic neoplasm is rare and represents less than 3% of all soft-tissue tumours [1].

DF can be classified according to its location as extra-abdominal, intra-abdominal, or abdominal wall [1]. Abdominal wall DF arises from musculoaponeurotic structures of the abdominal wall, most often from the rectus or internal oblique muscles and their fascial coverings [3].

Endocrine factors are highly implicated in this form of DF, which explains why young women during or after pregnancy are the most commonly affected group [1]. They may also occur secondary to trauma, following surgery, or related to hereditary syndrome familial adenomatous polyposis [1].

Typically, they present as a solitary slow growing, firm and painless mass [3].

On imaging, DF tends to be a fairly well-circumscribed solid mass and its appearance varies according to the amount and distribution of its histologic components (spindle cells, myxoid matrix, collagenous stroma) [1, 2].

Ultrasound (US) is a useful imaging technique in the initial screening of a palpable abdominal wall mass. On US, it appears as an oval soft-tissue mass with variable echogenicity [3]. DF can be associated with the fascial tail sign, which reflects thin linear extension along fascial planes, and the staghorn sign, indicating intramuscular finger-like extensions of the tumour [1, 2]. Vascularity is variable at colour Doppler US [1].

On CT, abdominal wall DF has variable attenuation, similar to or slightly higher than skeletal muscle [1, 2]. In larger masses, we may find a more heterogeneous appearance. Necrosis or calcification is very rare [1]. The majority of these tumours demonstrate mild-to-moderate enhancement [1].

On MRI, DF tends to have a heterogeneous pattern with high T2-weighted signal intensity early in its evolution, but becomes lower in T2 signal intensity as it evolves (collagen deposition increases) [1, 2]. Non-enhancing linear bands (band sign) are usually described, likely corresponding to the dense collagenous stroma [1].

Despite the characteristic imaging findings, definitive diagnosis must be established with histopathologic analysis [3]. Nevertheless, CT and MRI are the best imaging modalities for assessing resectability, surgical planning and follow-up [3]. Important imaging findings with surgical implications include the longitudinal extent and depth of the tumour, involvement of internal organs, and proximity to the costochondral junction or the lower ribs [1].

Surgery is the treatment of choice for progressive or symptomatic tumours, while a conservative approach is acceptable for tumours that are not causing notable impairment [3].

After surgical resection, the local recurrence of abdominal wall DF is about 15%-30% [1].

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

The definite histologic diagnosis was of dermoid-type fibromatosis.

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

Preoperative reevaluation CT

CT appearance of the abdominal wall mass

US appearance of the abdominal wall mass

Medical Imaging Analysis Report

I. Radiological Findings

According to the provided abdominal CT and ultrasound imaging data, a relatively well-defined soft tissue mass is observed in the right abdominal wall (lateral middle segment). On CT, its density is equivalent to or slightly higher than the surrounding muscle tissue, with no significant necrosis or calcification. After contrast enhancement, mild to moderate enhancement is seen. On ultrasound, a relatively homogeneous or partially altered echogenicity is noted, with a “fascia tail sign” and “antler-like extension sign” in some areas, suggesting a finger-like extension of the tumor along fascia or muscle bundles. The lesion is moderately deep and closely related to the surrounding abdominal wall musculature, but there is no clear evidence of involvement of intra-abdominal organs.

II. Potential Diagnoses

Based on the patient's age, clinical presentation, and imaging findings, the following potential diagnoses are considered:

- Abdominal wall desmoid-type fibromatosis

Characteristics: Commonly seen in women of childbearing age, typically presenting as a painless, slowly growing mass. Imaging often shows a well-defined lesion with finger-like extensions, with no tendency for distant metastases. - Other benign soft tissue tumors of the abdominal wall (e.g., lipoma, fibroma, etc.)

Characteristics: Lipomas typically appear as fat-density lesions on CT, while fibromas often have a uniform soft tissue density with mild enhancement. Based on current data, imaging features favor desmoid fibromatosis; however, differential diagnosis should still be considered. - Metastatic tumors of the abdominal wall

Characteristics: Patients typically have a surgical history or another known primary tumor. In this case, the patient has neither a prior surgical history nor an obvious primary malignancy, so the likelihood of metastatic disease is low.

III. Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s sex, age, painless and slow growth characteristics, imaging findings (relatively clear boundaries, mild to moderate enhancement, fascia tail sign, and finger-like intramuscular extension), and no specific abnormalities in laboratory tests, the most likely diagnosis is:

Abdominal wall desmoid-type fibromatosis

If further confirmation is needed, a core needle biopsy or surgical pathological examination is recommended to establish a definitive histological diagnosis.

IV. Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation Program

For confirmed abdominal wall desmoid-type fibromatosis, the treatment strategy generally depends on the size, location, and symptoms of the tumor:

- Conservative/Observation: For slow-growing lesions with mild or no symptoms and no functional impairment, close follow-up and regular imaging reviews can be conducted to monitor any changes.

- Surgical Resection: For tumors that demonstrate progressive enlargement, cause pain or functional impairment, or impact appearance or quality of life, surgery may be considered. Adequate surgical margins are necessary to reduce the recurrence rate.

- Pharmacological Treatment: For unresectable or high-risk recurrent cases, conservative medical approaches such as hormones, NSAIDs, or targeted therapy (e.g., tyrosine kinase inhibitors) may be considered.

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription Recommendations:

Because the abdominal wall muscles play a crucial role in trunk stability, a scientifically designed rehabilitation exercise plan is needed after surgery or during conservative treatment to maintain and improve core muscle tension and to avoid excessive stretching that could lead to reinjury.

- Initial Stage (Postoperative or Early Diagnosis):

· Focus on basic breathing exercises and core stability training (e.g., supine abdominal breathing, posterior pelvic tilt exercises).

· Low intensity, small range of motion for about 10–15 minutes each time, 1–2 times per day. - Intermediate Stage (After Wound Healing or Symptom Relief):

· Gradually increase core strength training, such as small-range curl-ups and bridge exercises (taking care not to overstretch the abdominal wall).

· Intensity can be progressively increased to a moderate level, each session lasting 15–20 minutes, 3–4 times per week, adjusted based on recovery status. - Late Stage (Recovery or Long-Term Maintenance):

· Strengthen overall endurance and perform resistance training, such as light dumbbell exercises, Pilates, or yoga.

· Exercise duration can be extended to 20–30 minutes per session, 3–5 times per week, while controlling movement range to protect the abdominal wall muscles.

Throughout the entire rehabilitation process, the “FITT-VP” principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and Progression) should be followed. Closely monitor whether the abdominal wall develops new pain, swelling, or other discomfort. If any such issues arise, seek medical evaluation promptly.

Disclaimer: This report is a reference analysis based on the available data and cannot replace in-person consultation or professional medical diagnosis and treatment. If you have any questions or if symptoms worsen, please consult a specialist promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

The definite histologic diagnosis was of dermoid-type fibromatosis.