Reichel’s syndrome of wrist: A rare entity

Clinical History

A 37-year-old male reported experiencing slight movement restriction in his right wrist for the past year. He had no history of trauma. Physical examination revealed diffuse oedema in the right wrist, without any visible redness or tenderness.

Imaging Findings

On coronal STIR and axial T2-weighted images (Figures 3a and 3c), multiple fairly defined intra-articular extensive T2/STIR hyperintense lobular masses with multiple subcentimetric hypointense areas are noted. These areas show blooming on GRE (Figure 3b), suggesting synovial loose bodies, within the carpal and wrist joint spaces, extending into the extensor and flexor compartments of the right wrist and closely abutting adjacent tendons. The same lesions show intermediate signal intensities on coronal T1 images (Figure 3d).

Discussion

A benign, rare entity called primary synovial osteochondromatosis is characterised by synovial metaplasia and hyperplasia, with frequent observations of cartilaginous nodules releasing loose bodies into the synovial cavity. This condition is also known as Reichel’s syndrome or Reichel–Jones–Henderson syndrome [1]. Synovial chondromatosis presents as cartilaginous foci in tendon sheaths, bursae, and synovial membranes. Initially, these cartilaginous foci develop as sessile structures with a strong synovial attachment, eventually becoming pedunculated and breaking free to become free intra-articular or periarticular loose bodies. After becoming free in the joint, they continue to grow thanks to the nourishment provided by the synovial fluid and eventually either reconnect to the synovium or are reabsorbed [2]. These loose bodies give the synovium a cobblestone appearance.

Intra-articular pathology is typical, but extra-articular cases have also been reported, typically involving tenosynovial structures. Primary synovial chondromatosis typically affects adults, predominantly men, in the third to fifth decades of life [2]. The most frequently involved joint is the knee, followed by the hip, elbow, and shoulder. The wrist is seldom affected. Men are more likely than women to be afflicted during the third to fifth decades of life [3]. This contrasts with secondary synovial chondromatosis, which occurs when underlying joint pathology, such as trauma (either a single traumatic event or repeated microtrauma), osteochondritis dissecans, advanced osteonecrosis, or Charcot neuropathic joint, results in synovitis and/or articular destruction. Secondary synovial chondromatosis results from mechanical injury to the intra-articular hyaline cartilage and typically affects individuals in their 50s and 60s [2].

Radiographs of primary synovial chondromatosis typically reveal several intra-articular calcifications, evenly distributed throughout the joint in 70%–95% of cases. Ring-and-arc or punctate calcifications frequently have a pathognomonic appearance, being numerous and quite similar in shape. Other features include joint effusion and extrinsic erosion of joints [3]. Radiographs can be normal in 5%–30% of primary intra-articular synovial chondromatosis cases. Arthrography, typically followed by CT or MR imaging, often depicts diagnostic features, with multifocal intra-articular chondral bodies seen as numerous circular filling defects. In secondary synovial chondromatosis, intra-articular loose bodies are fewer in number and variable in size, and radiographs show underlying joint pathology [3].

Given the presence of synovial proliferation and intra-articular loose bodies, a differential diagnosis could include lipoma arborescens, a rare entity in which the normal synovium is replaced by hypertrophied villi with marked deposition of mature lipocytes within them, manifesting as a characteristic fat signal intensity or density. Another consideration is tenosynovial giant cell tumour, a group of fibrohistiocytic tumours that arise from synovium, bursae, or tendon sheaths, which present as more confluent masses with a diffuse characteristic low intensity on MRI. A malignant lesion should be taken into account throughout the differential diagnostic process, including low-grade intraosseous chondrosarcoma extending into a joint. Findings from an MRI aid in differentiating synovial chondrosarcoma, as it is unusual for synovial chondromatosis to cause marrow invasion [3].

The most effective treatment for synovial osteochondromatosis in patients with ongoing symptoms is total synovectomy, which entails the removal of any loose cartilaginous nodules [5]. According to research, incomplete excision is likely the reason for recurrence following resection, so surgeons should ensure a comprehensive synovectomy is performed [5]. Moreover, monitoring the condition following surgery is helpful, even if there is little chance of malignant degeneration and recurrence.

Differential Diagnosis List

Final Diagnosis

Primary synovial chondromatosis

Liscense

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figures

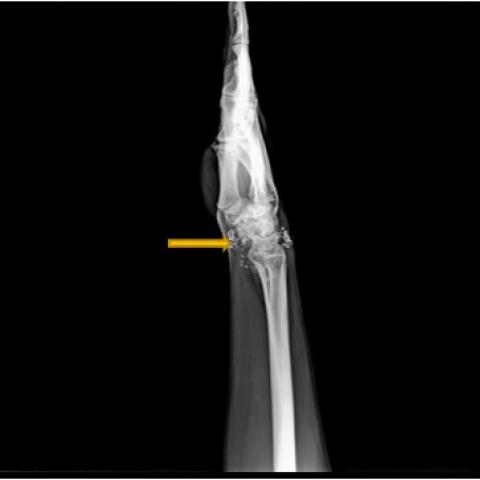

Radiograph of the right wrist

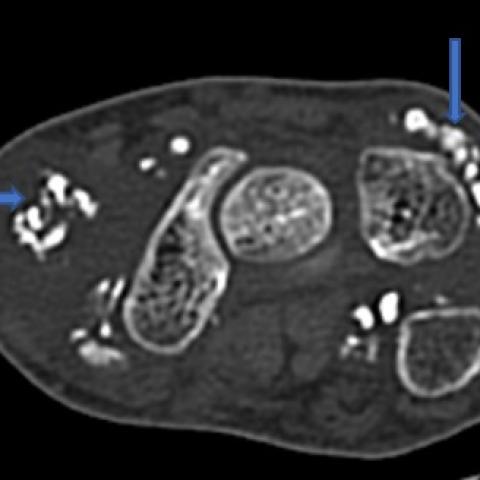

CT scan of the right wrist

STIR, GRE, T2- and T1-weighted

Imaging Findings

- Multiple irregular calcifications are visible in and around the right wrist joint, appearing in “rings-and-arcs” or punctate patterns.

- The joint space is reasonable, with no obvious erosion of the joint surfaces or extensive osseous destruction; mild soft tissue swelling is noted around the joint.

- CT axial, sagittal, and coronal reconstructions clearly show these calcifications primarily located within the joint cavity and/or around the tendon sheaths, scattered in distribution.

- On MRI, some lesions exhibit high signal intensity on T2 sequences and “blooming” artifacts on GRE sequences, consistent with calcified or cartilaginous components.

- No apparent signs of fracture, and no obvious external soft tissue mass infiltration or bone marrow infiltration signal.

Possible Diagnoses

- Primary Synovial Chondromatosis (Primary Synovial Osteochondromatosis):

- Typically presents as multiple small cartilaginous nodules within the joint or tendon sheaths, often bearing “rings-and-arcs” or punctate calcifications.

- It commonly occurs in young and middle-aged adults, more often in males, and usually involves the knees, hips, elbows, or shoulders; the wrist joint is less commonly affected but has been reported.

- Lipoma Arborescens:

- A rare synovial lesion characterized by marked proliferation of fatty tissue on the synovium, typically demonstrating a classic fat signal on MRI.

- In this case, the primary feature is multiple calcified foci, and there is no prominent fatty signal thickening, so this diagnosis is relatively less likely.

- Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor:

- May appear as a focal or diffuse mass within the joint or tendon sheath. On MRI, it typically shows low signal intensity. Calcification is less common than in synovial chondromatosis.

- The imaging features in this case, particularly the multiple calcified nodules with diverse shapes, favor synovial chondromatosis.

- Secondary Synovial Chondromatosis:

- Often secondary to structural or degenerative changes in the joint (e.g., trauma, osteoarthritis). Currently, there are no signs of notable trauma or degeneration, and the patient is relatively young, so this is less likely.

- Malignant Lesions such as Chondrosarcoma:

- In suspected chondrosarcoma or synovial chondrosarcoma, bone marrow destruction or a locally invasive soft tissue mass is often present.

- There is no obvious erosive change or bone marrow lesion on the imaging in this case, making malignancy less likely.

Final Diagnosis

Considering the patient’s age (37 years), clinical symptoms (mild restriction of right wrist mobility, chronic course, no history of trauma), and imaging findings of multiple “rings-and-arcs” or punctate calcifications around the joint and tendon sheaths, the most likely diagnosis is Primary Synovial Chondromatosis (Synovial Osteochondromatosis).

Treatment Plan and Rehabilitation

Treatment Strategy:

- If symptoms are mild and lesions remain stable, periodic follow-up may be appropriate to monitor disease progression.

- For persistent symptoms or significant functional limitations, arthroscopic or open surgical removal of intra-articular/tendon sheath loose bodies coupled with synovectomy is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription:

- Preoperative/Conservative Phase:

- Engage in gentle wrist exercises, such as fist clenching and finger extension, as well as forearm pronation and supination, avoiding heavy loads or frequent repetitive rotation.

- Gradually expand the range of motion and perform wrist movement exercises within safe limits to maintain baseline joint flexibility.

- Postoperative Phase:

- Early Stage (1–2 weeks): Emphasize passive or assisted range-of-motion exercises at low intensity, 3–5 sessions per day, each lasting around 5–10 minutes, alongside ice packs or gentle compression to reduce swelling.

- Intermediate Stage (2–6 weeks): Gradually increase active motion exercises, initiate grip strengthening, and light resistance training for the wrist. Frequency can be increased to 2–3 times daily, each session lasting 15–20 minutes.

- Late Stage (6 weeks and beyond): Under the guidance of a physician or therapist, conduct functional training—such as wrist coordination drills and light dumbbell or resistance band activities—to restore muscle strength and joint stability.

- Follow an individualized FITT-VP principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, Progression). Routine follow-ups are recommended to monitor any changes in wrist pain, swelling, or range of motion.

- If the patient has osteoporosis or a compromised cardiopulmonary condition, exercise intensity should be moderated, with adequate rest periods and continuous monitoring of heart rate and other physiological indicators to ensure safety.

Disclaimer

This report offers a preliminary analysis based on current imaging and clinical details and is intended for reference only. It does not replace in-person consultations or professional medical advice. If any concern arises or your condition changes, please seek further evaluation and care promptly.

Human Doctor Final Diagnosis

Primary synovial chondromatosis