A patient with a 2-year history of pain in the left pelvic area, decreased mobility of the hip and difficulty walking, unrelieved by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy, was referred for repeat radiography. This demonstrated almost complete osteolysis of the left os ilium with extension to the ipsilateral acetabulum, os pubis.

The patient initially presented with pain in the left pelvic area, decreased mobility of the hip and difficulty walking. Laboratory results were normal. Plain film radiography performed at this time showed no abnormalities. The patient was treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but, because the pain was not relieved, the patient was referred for repeat radiography 2 years later. At this time plain film radiography demonstrated almost complete osteolysis of the left os ilium with extension to the ipsilateral acetabulum, os pubis (Figure 1a). Bone scintigraphy showed increased activity in the osteolysed region.

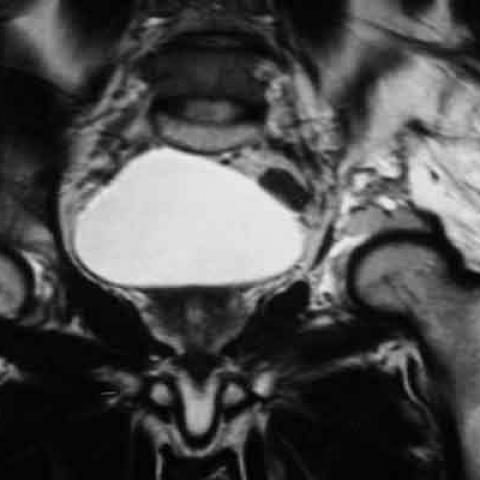

To define the extent of the osteolysis more precisely, computed tomography (CT) examination was performed. CT confirmed osteolysis of the left ilium and acetabulum, os pubis and demonstrated disruption of bone cortices. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a soft tissue process around the left hip which was iso-hypointense with muscle on T1-weighted imaging and was of high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging (Figures 1b,1c). It showed contrast enhancement on T1-weighted sequences after intravenous administration of gadopentate dimeglumine.

Multilocular fine needle aspiration biopsy and tru-cut biopsy were performed for pathological examination. This revealed bone destruction by hyper vascular fibrous tissue and enlarged bone marrow spaces containing numerous thin-walled capillary vessels. Open surgery and surgical biopsies also confirmed these findings.

Massive osteolysis of Gorham is a combined clinical, radiographic, and histological entity characterized by non-familial histologically benign vascular proliferation originating in bone and producing complete osteolysis of all or a portion of bone. In a review of the literature Choma et al. (1) noted 98 reported cases. The disease may become evident in men and women of all ages, although most cases are discovered before the age of 40. (2)

The disease is of unknown etiology and may affect any bone, although the pelvis, shoulder, and mandible are favored sites (1,2). Progressing radiographic findings are essential. The initial changes are well circumscribed or expanding subcortical or intramedullary osteolytic areas, generally with a tendency to enlarge. As in this patient, osteolysis of involved bones is almost complete and can lead to complete resorption in severe cases. (2)

Histological diagnosis relies on microscopic evidence of intraosseous angiomatous changes, involving blood vessels more often than lymph vessels, although mixed types have been reported.

Although the disease usually stabilizes spontaneously and the angiomatous areas are replaced by fibrous tissue, the ultimate extent of the disorder cannot be predicted from the initial lesions. As in this case and as mentioned in the literature, patients do not complain of severe symptoms; most reports are loss of strength, increasing pain, and difficulties walking. A pathological fracture may reveal the disease, while skin pallor, swelling of the affected area, shortening and bowing of an extremity, and scoliosis are also reported. In cases of vertebral localization, neurological signs may be present. When the chest is affected, pleural effusion or chylothorax may occur. However, clinical signs are usually mild compared to radiological changes. (3)

Radiologically, early lesions consist of well-circumscribed intramedullary and subcortical lucencies resembling osteoporosis, generally with a tendency to enlarge. The concentric reduction of bony structure leads to an appearance that mimics a licked stick of candy, which may spontaneously arrest or continue until the bone disappears, hence the term 'vanishing bone disease'. In severe cases, there is complete resorption of the involved bones in later stages, as seen in this case. Arteriography usually does not reveal profound vascular abnormality, although a faint blush has been described. (4)

Computed tomography is useful in the delineation of soft tissue extension and allows biopsy guidance. Three-dimensional CT reconstructions can be very valuable to the orthopedic surgeon planning a reconstruction attempt. (3) Thus suspected Gorham disease is an indication for CT.

Magnetic resonance imaging, by demonstrating changes in signal intensity over time, could be useful in differentiating early, active stages from later stages where fibrous replacement has occurred. However, pathological diagnosis appears to be more specific than any signal changes.

The ultimate extent of the disease can not be predicted from the initial lesions, and complications are variable, ranging from minimal disability to death (from involvement of vital organs, which occurs in 16% of cases, or spinal or chest wall localization, which occurs in 38% of cases).

Therapeutic approaches to the disease are not well defined because of the small number of reported cases and the usual spontaneous stabilization of the disease. Medical treatment (with complex cocktails of hormones, calcium salts, and vitamins) has failed to show efficacy. Treatment has focused primarily on radiotherapy; prosthetic devices, bone grafting and surgical extirpation have also been employed. (3)

Idiopathic massive osteolysis of Gorham

From the provided imaging (including X-ray and MRI), a large area of decreased density can be observed in the left iliac bone with an almost complete osteolytic change. The lesion has involved the ipsilateral acetabulum and part of the pubic region. The boundaries are irregular, and there is a noticeable “vanishing” phenomenon in the local bone structure. No obvious soft tissue mass is seen, but some changes in the soft tissue space can be noted. On MRI, the signal in the left pelvic region is markedly reduced compared to the normal contralateral side, and the trabecular bone structure is blurred or missing, suggesting active bone destruction. No apparent cortical sclerosis or periosteal reaction is noted.

The possible etiology is related to abnormal proliferation of blood vessels or lymphatic vessels. Clinically, it presents with progressive osteolysis, potentially causing bone to “disappear.” Radiologically, it is generally seen as progressive, localized or diffuse osteolysis, typically without obvious periosteal or soft tissue reactions. The imaging findings in this case align with previous reports, along with chronic pain and characteristic disappearance of bone lesions.

Malignant tumors can lead to osteolytic destruction, such as multiple myeloma or metastatic bone tumors. However, they typically show more extensive bone destruction, periosteal reactions, or surrounding soft tissue masses, and may be accompanied by other systemic symptoms or typical laboratory abnormalities (e.g., irregular proteins or tumor markers). Considering this case’s features and the relative absence of other tumor manifestations, this possibility is less likely.

Chronic inflammation or infection can also cause focal bone destruction, but it is often associated with clues such as sinus tract formation, sclerotic margins, or significant local soft tissue swelling. The imaging findings are not typical for such conditions, and the clinical presentation does not suggest marked inflammation or infection, making this diagnosis less likely.

Considering the patient’s age, chronic pain duration, the osteolytic pattern in imaging, and references from the literature, the most likely diagnosis is Gorham’s Disease (Extensive Vanishing Bone Lesion).

If further confirmation is needed and the clinical conditions allow, a biopsy can be performed to obtain pathological evidence confirming vascular or lymphatic proliferation causing bone destruction.

Currently, there is no universally recognized or definitively effective treatment for Gorham’s disease, and many cases may spontaneously stabilize over time. Common treatment measures include:

During rehabilitation, it is critical to consider bone fragility, pain levels, and functional limitations, progressing the exercise regimen gradually:

The entire rehabilitation process should be carried out under professional supervision, with close monitoring of bone and joint responses. If significant pain or discomfort arises, adjust the program promptly.

Disclaimer: This analysis report is for reference purposes only and does not replace in-person medical consultations or professional advice. If you have any concerns or if symptoms worsen, please seek medical attention promptly.

Idiopathic massive osteolysis of Gorham